|

The Story of Competence

The word competence was first used in

linguistics by Chomsky (1965) to distinguish between knowledge of

language in the abstract (competence) and the way in which knowledge is

realized in the production and interpretation of actual utterances

(performance). Chomsky’s idea of competence as knowledge of language

apart from its use was criticized by Hymes (1972), who countered that

not only does competence refer to the individual’s knowledge of the

forms and structures of language, but it also extends to how the

individual uses language in actual social situations. Hymes described

four kinds of knowledge that speakers use in social situations: what is

possible to do with language, what is feasible, what is appropriate, and

what is actually done. This combination of knowledge and use Hymes

called communicative competence, which many people

contrasted with Chomsky’s theory, and the latter came to be known as linguistic competence.

Hymes’s ideas were the basis for an applied linguistic theory

of communicative competence put forward by Canale and Swain (1980), who

related linguistic acts in social situations to underlying knowledge. In

applied linguistics, language testing, and language teaching,

communicative competence was thought of as a characteristic of a single

individual, a complex construct composed of several component parts that

differentiated one individual from others.

Interactional competence (IC) builds on the theories of

competence that preceded it, but it is a very different notion from

communicative competence. Kramsch (1986) wrote that IC presupposes “a

shared internal context or ‘sphere of inter-subjectivity” (pg. 367) and this is

what clearly distinguishes IC from previous theories of competence.

Young (2011) listed the following component parts of IC:

- Identity resources

- Participation framework: the identities of

all participants in an interaction, present or not, official or

unofficial, ratified or unratified, and their footing or identities in

the interaction

- Linguistic resources

- Register: the features of pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar that typify a practice

- Modes of meaning: the ways in which

participants construct interpersonal, experiential, and textual meanings

in a practice

- Interactional resources

- Speech acts: the selection of acts in a practice and their sequential organization:

- Turn-taking: how participants select the next

speaker and how participants know when to end one turn and when to begin

the next

- Repair: the ways in which participants respond to interactional trouble in a practice

- Boundaries: the opening and closing acts

of a practice that serve to distinguish a given practice from adjacent

talk

IC involves knowledge and employment of these resources in

social contexts. However, the fundamental difference between IC and

communicative competence is that an individual’s knowledge and

employment of these resources is contingent on what other participants

do; that is, IC is distributed across participants and varies across

different interactional practices. And the most fundamental difference

between interactional and communicative competence is that IC is not

what a person knows, it is what a person does together with

others in specific contexts.

Teaching Interactional Competence

Teaching IC might involve two moments. In the first, learners

are guided through conscious, systematic study of the practice, in which

they mindfully abstract, reflect on, and speculate about the

sociocultural context of the practice and the identity, linguistic, and

interactional resources that participants employ in the practice. In the

second moment, learners are guided through participation in the

practice by more experienced participants. There is considerable support

for a pedagogy of conscious and systematic study of interaction in the

work of the Soviet psychologist Gal’perin and his theory of

concept-based instruction. The new practice to be learned is first

brought to the learner’s attention, not in small stages but as a

meaningful whole from the very beginning of instruction.

Concept-Based Instruction

One example of concept-based instruction is the curriculum

designed by Thorne, Reinhardt, and Golombek (2008) to help international

teaching assistants (ITAs) at a U.S. university develop interactional

skills in office hours. The practice they taught was office-hour

interaction between an ITA and an undergraduate student, and they

focused on how ITAs give directions to students. For the first part of

their program, ITAs in training engaged in discussion and activities

that centered on the relation between context and the resources

participants employ in order to construct, reproduce, or resist a

particular practice. They were then exposed to transcriptions of (a)

expert office-hour interactions and (b) office-hour interactions led by

ITAs. They were asked to reflect on the configuration of identity,

verbal, nonverbal, and interactional resources that are employed by TAs

in giving directions to students by discussing four questions about the

transcriptions.

- Who are the participants? What do you think their relationship is?

-

Where do you think the session could be taking place?

-

What is the teacher trying to get the student to do?

-

What language does the teacher use to accomplish this?

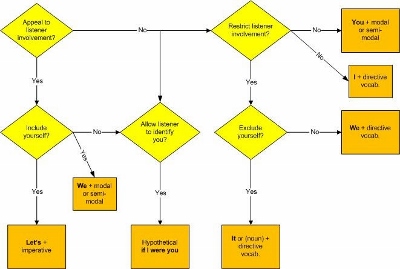

In the next step, Thorne et al. (2008) followed Gal’perin’s

suggestion to provide a materialization that represents connections

between the contextual features of the practice and the verbal resources

that participants employ to construct it. The schema for complete

orienting basis of action (SCOBA) that Thorne et al. developed is

represented in Figure 1 to show visually the relationship between

context in office hours and an ITA’s choice of pronoun to direct a

student’s action.

Figure 1. SCOBA of Pronoun Choice in ITA Office-Hour Directives (click to enlarge)

Source: Thorne et al. (2008).

The ITAs used this materialization individually to mediate

cognitive connections between context and language form, which they then

discussed verbally among themselves. The final phase of the

concept-based curriculum was an explicit comparison, which the trainers

provide, of pronoun use in directives in the expert corpus and the ITA

learner corpus (see Table 1). ITA trainees were then asked to discuss

the differences between directives in the expert corpus and directives

in the ITA corpus and offer their explanations for the

differences.

Table 1. Comparison of Pronoun Use in Directives in the Expert Corpus and the ITA Learner Corpus

|

Directive construction word/phrase |

ITA learner corpus |

Rate per 10k |

Expert corpus |

Rate per 10k |

Ratio of over/underuse |

|

I suggest OR my suggestion |

30 |

3.35 |

5 |

0.28 |

12.0314 |

|

You should |

94 |

10.50 |

83 |

4.63 |

2.2710 |

|

Let’s |

41 |

4.58 |

118 |

6.58 |

0.6967 |

|

We |

146 |

16.31 |

881 |

49.1 |

0.3308 |

|

I would |

0 |

0.00 |

64 |

3.57 |

– |

|

Total words |

89,489 |

|

179,446 |

|

| Source: Thorne et al. (2008).

The advantage that I see of a concept-based approach to

instruction is that a conceptual analysis of a specific practice

encourages portability of the same concepts to other practices in the

domain of academic discourse, whereas in bottom-up or inductive

learning, learners are required to infer general principles from

multiple examples and they must identify a new exemplar as similar to

ones that they have already met. In contrast, a top-down concept-based

approach encourages learners to develop a concept, or theory, of the

domain of instruction. This concept can then mediate their understanding

of other practices in the same domain. In other words, the ITAs

experiencing Thorne et al.’s (2008) concept-based curriculum not only

learn directives in university office hours but can also apply their

theoretical knowledge to other practices in other interactional

practices at U.S. universities.

Conclusion

Interactional competence can be seen as a set of identity,

linguistic, and interactional resources that are distributed among

participants in a specific situation or discursive practice. The

resources include knowledge of the relationships between the forms of

talk chosen by participants and the social contexts in which they are

used. But more than individual knowledge, IC is the construction of a

shared mental context through the collaboration of all interactional

partners. And through concept-based instruction, learners come to

understand that the context of an interaction includes the social,

institutional, political, and historical circumstances that extend

beyond the horizon of a single interaction.

Learners’ development in IC has been reported in longitudinal

studies in which learners’ contributions to discursive practices have

been compared over time. Systematic study by learners of the details of

interaction in specific discursive practices may benefit development of

interactional competence, but we await empirical studies to test that

claim.

In the assessment of interactional competence, several authors

have claimed that a close analysis needs to be made of the identity,

linguistic, and interactional resources employed by participants in an

assessment practice. This interactional architecture of the test may

then be compared with discursive practices outside the testing room in

which the learner wishes to participate. If the configuration of

resources in the two practices is similar, then an argument can be made

to support the generalization of an individual’s test result because the

testee can redeploy resources from one practice to another. Assessing

interactional competence is challenging, however, because IC is locally

contingent and situationally specific, while assessment often requires

comparing language practices across contexts. Future work in the

learning, teaching, and assessment of interactional competence may

resolve this tension.

References

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of

communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 1–47.

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hymes, D. (1972). On communicative competence. In J. B. Pride

& J. Holmes (Eds.), Sociolinguistics: Selected

readings (pp. 269–293). Harmondsworth, England:

Penguin.

Kramsch, C. (1986). From language proficiency to interactional

competence. Modern Language Journal, 70,

366–372.

Thorne, S. L., Reinhardt, J., & Golombek, P. (2008).

Mediation as objectification in the development of professional academic

discourse: A corpus-informed curricular innovation. In J. P. Lantolf

& M. E. Poehner (Eds.), Sociocultural theory and the

teaching of second languages (pp. 256–284). London, England:

Equinox.

Young, R. F. (2011). Interactional competence in language

learning, teaching, and testing. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook

of research in second language teaching and learning (Vol. 2,

pp. 426–443). New York, NY: Routledge.

Richard F. Young is professor of English linguistics

and second language acquisition at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

His recent books include Language and Interaction andDiscursive Practice in Language Learning and

Teaching. |