|

J. Dylan Burton

|

|

Paula Winke

|

Teachers and researchers around the world know that foreign, second, and additional language (henceforth called L2) learning is complex. In instructed settings, L2 learning depends on good classroom practice, proper syllabus and curriculum design, meaningful assessments, and optimal environmental/social factors. Even if educators try their absolute best to create the perfect classroom, not all learners will be equally successful at various points in time in developing proficiency in their L2. Much of this variability may be due to individual differences (hereafter, IDs) within each learner, such as intelligence, age, and personality (Hummel, 2014). Some IDs may not be static (unchanging) traits, however, and may be related to shifts in emotions and opinions of a given topic or task; thus, they are affective (MacIntyre et al., 2016). Affective IDs are dynamic and subject to change throughout a learners’ time spent learning a language. Some affective IDs refer to negative emotions, such as anxiety, while others are principally positive, such as motivation, grit, and willingness to communicate (WTC). In this special issue of the TESOL “AL Forum,” we argue for the importance of creating learning spaces that build learners’ positive orientations towards language learning as this is often a crucial aspect of achievement (Hummel, 2014). When educators focus on the positive, we believe they will also necessarily see a concomitant reduction of the negative.

At first glance, positive affective IDs like motivation, grit, and WTC may all seem similar as they all center around L2 learners’ desire to learn the L2. Motivation, the most familiar and researched of these, is generally considered to be the learners’ overall desire to learn and acquire the language of interest. Motivation can be shaped by internal and external factors, like one’s love of learning the language and one’s parents putting pressure on one to learn the language for future advancement, respectively, and may shift over a learner’s lifetime or even throughout the day. Closely related to motivation, grit is characterized by hard work, perseverance, effort, and consistent interest (Sudina et al., 2020). Gritty individuals have a strong, long-lasting desire to learn that goes beyond motivation. They stick with it even in the face of challenges or failure. WTC, on the other hand, refers to the “long-lasting tendencies and immediate situational influences on the decision to speak or to remain quiet” (MacIntyre et al., 2016, p. 315): Learners with a high amount of WTC are more likely to speak in class and may get more practice using the L2 than those with a low amount, which means they may get more feedback and may have more opportunities to self-repair. This may explain why they may tend to learn more. While a motivated learner may be more willing to communicate, a speaker that is willing to communicate may not necessarily be motivated to learn. Thus, these IDs are related, but they are separate: Having a high amount of one does not necessarily mean the others are high too.

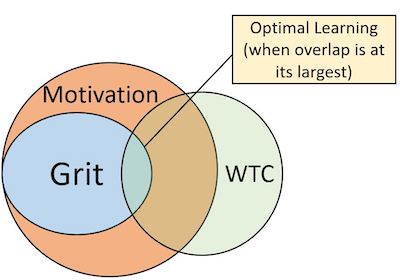

The way we imagine these three related positive affective traits for a hypothetical language learner is presented in Figure 1. We imagine that these “spotlights” may expand or contract in size based on the individual, and those sizes may change as each individual changes how they learn over time. Likewise, the three spotlights can move about or shift in location relative to one another so that they may overlap to greater or lesser extents across individual learners at any point in time; the spotlights may also move about and shift for each individual learner over time. We imagine that all three of these affective IDs are good for L2 learning, so we posit that a person’s best learning condition may occur when the ground covered by all three is at the maximum size for that person. Thus, there probably are two truths: Each person has a different-sized, maximal overlap of the three affective IDs; and it is normal for people to have more or less of an overlap among the three affective IDs at different stages and points in time along the person’s L2 learning pathway. Thus, these three IDs are dynamic in at least three ways: They change in size, they change in relation to each other, and those relationships change over time.

Figure 1. The relationship between positive affective IDs.

If there are so many differences amongst our learners, what then is the implication for educators? We believe it may be possible to leverage research knowledge about positive affective IDs to enhance students’ learning outcomes. In the case of motivation, research in SLA has shown that it is more than a desirable aspect of language learning: It is essential. It is multidimensional in nature because motivation can come from inside oneself (intrinsic) or from outside sources (extrinsic). Regardless of its source, however, it may be primarily built inside the language classroom. This means that teachers have a key role in fostering students’ interests and desires to learn English in ways that can enable them to achieve their goals. This may be done through exciting innovations, such as computer assisted language learning; content-based teaching such as Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) or English as a Medium of Instruction (EMI); linking learning with culture; and designing more authentic, relevant tasks that speak to learners (Lamb, 2017). These changes in teaching strategy can have a number of benefits, such as creating new and greater opportunities to communicate, as well as strengthening learner autonomy and agency.

Grit has also proven to be a trait possessed by successful individuals, particularly the highest achievers. It may even be as important as intelligence, aptitude, and talent as it can help learners overcome obstacles of almost any type. It appears there are two key defining elements of language learning grit: One is a strong, higher-order goal that promotes perseverance and hard work, while the second is consistent interest in the language the student is learning (Sudina et al., 2020). Both of these, in particular perseverance and hard work, have been found to associate with L2 proficiency. In the language classroom, grit should be seen as distinct from lower-order goals such as the need to complete pedagogical tasks or homework assignments as these goals are imposed externally rather than arising intrinsically. It may be possible to cultivate grit in a number of ways by setting long-term language learning goals which are realistic and clear and held to a high standard.

Finally, the third positive affective ID, WTC, is also a fundamental trait teachers can amplify. When a learner uses the language to communicate, the learner is practicing what they know, and at the same times receives feedback on what works (e.g., “Everyone understood me!”), and what does not work (e.g., “They didn’t understand that word I used, so I am either saying it wrong, or using the wrong word.”). Additionally, speaking is like expertly greasing the wheels of a bicycle: The more it is done, the better the bicycle gets at running efficiently and smoothly. WTC is a necessary precursor for one to get practice, which in turn brings about implicit or explicit feedback that helps the person’s language development and acquisition. This indicates that there is a special role for teachers to create classroom environments that provide learners a safe space to use their L2. Zarrinabadi (2014) found that teachers had a direct effect on both lowering and raising learners’ WTC. In particular, patient, engaged teachers that were open to topic selection and carefully chose when and when not to correct errors were more likely to make learners’ more willing to communicate.

From these examples above, it is clear that teachers play an important role in building positive affective traits that factor into language learning. Going back to Figure 1, we see the optimal learning space at the intersection of motivation, grit, and WTC. If teachers can put learners at ease while also building lifelong motivation and learning practices, learners may benefit tremendously by becoming more autonomous, engaged, and successful L2 users.

This does not come without challenges. Many aspects of L2 learning are by their very nature demotivating and can have a negative impact on the learner. When placing learners into different levels, for example, it is common to end up with a range of abilities within one classroom. Some learners will be stronger, while others will be weaker in some areas. If achievement is measured on the same standard, weaker students begin the year with far more progress to make than stronger students. This can be demotivating, especially if expectations are too demanding for lower proficiency learners. An ideal situation is to measure progress within each student by tracking their individual language learning gains over time, as well as measuring the effort they put into their work. This would put all students on equal ground and create a fairer, more equitable learning environment, which may build learners’ IDs, creating a circular and reciprocal, upward-moving learning spiral.

References

Hummel, K. M. (2014). Introducing second language acquisition: Perspectives and practices. Wiley Blackwell.

Lamb, M. (2017). The motivational dimension of language teaching. Language Teaching, 50(3), 301–346. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444817000088

MacIntyre, P. D., Gregersen, T., & Clément, R. (2016). Individual differences. In G. Hall (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of English language teaching (pp. 310–323). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315676203

Sudina, E., Brown, J., Datzman, B., Oki, Y., Song, K., Cavanaugh, R., Thiruchelvam, B., & Plonsky, L. (2020). Language-specific grit: Exploring psychometric properties, predictive validity, and differences across contexts. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching. (Advance online publication.) https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2020.1802468

Zarrinabadi, N. (2014). Communicating in a second language: Investigating the effect of teacher on learners’ willingness to communicate. System, 42, 288–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2013.12.014

J. Dylan Burton is a PhD student in the Second Language Studies Program at Michigan State University. His research interests include language assessment, psycholinguistics, and nonverbal behavior.

Paula Winke is a Professor in the Department of Linguistics, Languages, and Cultures at Michigan State University. She is Director of the Second Language Studies Program and co-editor of Language Testing.

|