|

Detong Xia

|

|

Hye K. Pae

|

An Introduction to Phrase Frames in Business Discourse

English is used as an internationally communal language in the business world. Business English is a form of English for specific purposes (ESP). It refers to the English language used not only in the business world for international trade, negotiations, and finance, but also for business communication required in the workplace, including presentations, meetings, written reports, and formal correspondence. Business emails are a medium of exchanging messages for the purpose of carrying out business activities via electronic devices, wherein practicing professional decorum and formality is expected. Learners of business English (LBEs) tend to face challenges in composing professionally-crafted business emails. Business emails written by LBEs often contain expressions that might be viewed as less formal or even demanding (e.g., you must do, you should know; Qian & Pan, 2019).

Corpus-based research of English phraseology has provided ample evidence suggesting that conventionalized communicative functions are expressed through specific linguistic forms and that different genres prioritize specific sets of multi-word sequences. An analysis of multi-word sequences and their discourse functions in a particular genre can contribute to the course design and learning outcomes of ESP courses. However, few studies to date have investigated how multi-word sequences are used in business discourse. Our study focuses on phrase frames (Fletcher, 2002-2007) which are multi-word sequences that contain one variable slot (indicated by *) fillable with one of the multiple candidate words. For example, the phrase frame would be * to could have happy, able, willing, required, or glad as a potential filler in the variable slot (e.g., would be happy to). We conducted a systemic investigation of phrase frames used in business emails written by LBEs, compared to those by working professionals (WPs), to examine the usage patterns of phraseology in business discourse. The following research question guides this study: What are the differences in phrase frames used in business emails by LBEs and WPs in terms of communicative functions?

The Study

Corpus Data

This study used the email corpora of LBEs and WPs. The LBE corpus included 1,413 learner emails (165,609 words) written based on prompts for hypothetical business scenarios (e.g., making requests, providing solutions, and giving advice) from the Education First-Cambridge Open Language Database (Huang et al., 2018; https://corpus.mml.cam.ac.uk/). The WP corpus contained 1,145 email entries (168,940 words) from the database of the University of California Berkeley Enron Email Analysis Project (https://bailando.berkeley.edu/enron_email.html).

Phrase Frame Identification and Functional Classification

We focused on four-word phrase frames with one variable slot within the phraseological unit. All phrase frames were extracted using the kfNgram software (Fletcher, 2002-2007). Phrase frames were classified into three functional categories, based on Biber et al. (2004), including stance expressions, discourse organizers, and referential expressions. Table 1 shows the definitions and examples of the three functional categories.

Table 1

Definitions of the three functional categories with phrase frame examples.

|

Functional Categories |

Definitions |

Phrase Frames [Fillers] |

|

Stance Expressions |

Describing the speaker’s attitude, stance, or assessment of the situation |

would be * to [happy, sufficient, subject, helpful]

it is * to [important, timely, better, wise] |

|

Discourse Organizers |

Showing discoursal relationships between prior and subsequent discourse |

I am * that [told, assuming, concerned, sorry]

if we * to [need, want, decide] |

|

Referential Expressions |

Identifying entities and contexts |

the * of the [end, impact, status, office]

as * as possible [soon, quickly, often] |

Findings

1. The LBEs and WPs have different profiles of phrase frame usage

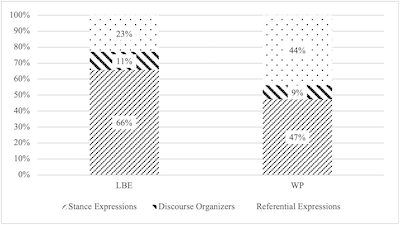

The LBEs and WPs showed different distributions of phrase frame usage in the three functional categories. As shown in Figure 1, the LBEs heavily relied on stance expressions. In contrast, the WPs used phrase frames more frequently for stance expressions and referential expressions than for discourse organizers.

Figure 1. The functional distribution of phrase frames in the LBE and the WP corpora.

2. Phrase frames incorporating modal verbs: Learners’ use of stance expressions may sound demanding

Many of the phrase frames for stance expressions contained modal verbs to express ability, necessity, request, obligation, or suggestion. The WPs frequently used phrase frames incorporating would (e.g., we would * to [like, love, need, hope]; I would * that [think, argue, suggest, recommend]). However, the LBEs dominantly used phrase frames including can (e.g., you can * your [change, make, prepare]; you can * the [return, buy, greet, finish]). Given that would is considered to be a more politeness-laden modal verb than can for expressing obligation and request, the frequent use of can-incorporated phrase frames indicated that the LBEs were less apt to convey politeness in business emails.

When the need- and should-incorporated phrase frames were used, the LBEs tended to use a second-person pronoun you (e.g., you * need to [will, really, also]; you should * to [try, go]) to express the necessity or obligation of the other party. The overuse of a second-person pronoun with the modal verb can, need, or should may sound overly aggressive in professional business communication. In contrast, the WPs frequently used the need- and should-incorporated phrase frames with the first-person plural pronoun or a third-person reference (e.g., we * need to [would, will, probably]; I think * should [we, Jeff, Donna]) to express their suggestions.

3. The differential use of referential phrase frames suggests that learners follow written business decorum less than working professionals

Compared to the WPs, the LBEs used less referential phrase frames, suggesting that learners were not on par with professionals in the practice of written conventions specialized for business purposes. Biber et al. (2004) reported that referential expressions appeared more frequently in academic writing, whereas stance expressions were most commonly used in conversation. Given that academic writing is more formal than conversation, the findings of this study suggest that LBEs tend to compose their business emails in a conversational fashion, while WPs are more likely to conform to written conventions suitable for optimal business decorum and formality.

Conclusion and Pedagogical Applications

The findings of this study indicate that phrase frames serve as a means to express workplace decorum and formality in business email communication. Widdowson (2000) suggests that linguistic patterns informed by corpus-based studies need to be recontextualized in the classroom to make them realistic for learners. The results of this study offer useful insights into pedagogical applications. First, it is suggested that instructors of business English provide explicit instruction on how to properly use modal-verb incorporated phrase frames to write effective business emails. Requests, directions, and invitations in business emails involve a varying degree of politeness and require considerable sensitivity in order not to invoke an unintended response. The following activities might be utilized in classrooms with variations as necessary:

- The instructor compiles a learner corpus from students’ mock business emails for requests, directions, and invitations that fit various situations in the workplace.

- The instructor makes two columns on the board and places a set of students’ phrase frame production associated with modal verbs in the first column.

- The instructor explicitly explains a possible range of expressions and interpretations for each of those expressions by paying special attention to modal verbs embedded in phrase frames on a politeness continuum.

- Students produce refined phrase frames in terms of politeness in the second column. This can be done in the whole group, small groups, or dyads.

- The instructor provides explicit feedback on the students’ revision and further discusses it as needed.

Second, business English instructors are encouraged to raise learners’ awareness of and sensitivity to the three functional categories of phrase frames and help them use appropriate phrase frames to improve their language use for business purposes. To increase authenticity, instructors can use examples collected from real-world workplace situations to develop realistic dialogs for classroom activities. A suggested conscious-raising activity is as follows:

- The instructor provides students with real-world emails written by WPs. Students’ self-collected email excerpts from online or textbooks can also be used instead.

- Students underline phrase frames and identify commonly used phrase frames for each functional category. This can be done individually, in pairs, or in small groups.

- The instructor writes on the board phrase frames that students have identified as target phrases for each category.

- Students compose business emails using the target phrase frames covering all three categories.

Lastly, instructors of business English can help learners familiarize themselves with phrase frames used by working professionals and solidify phrase frame knowledge through task-based language teaching (TBLT). TBLT is particularly useful, given that it provides students with rich input through realistic job-related tasks as contextualized activities. The instructor can also have students role-play at different organizational hierarchies in various scenarios when they write simulated business emails in classrooms.

In conclusion, teaching phrase frames provides an effective means to developing learners’ email writing in business contexts. It not only builds learners’ effective communication skills in the workplace, but also increases their career opportunities.

References

Biber, D., Conrad, S., & Cortes, V. (2004). If you look at ...: Lexical bundles in university teaching and textbooks. Applied Linguistics, 25(3), 371–405.

Fletcher, W.(2002-2007). KfNgram. Annapolis, MD: USNA. http://www.kwicfinder.com/kfNgram/kfNgramHelp.html.

Huang, Y., Murakami, A., Alexopoulou, T., & Korhonen, A. (2018). Dependency parsing of learner English. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 23(1), 28–54.

Qian, D., & Pan, M. (2019). Politeness in business communication: Investigating English modal sequences in Chinese learners’ letter writing. RELC Journal, 50(1), 20–36.

Widdowson, H. G. (2000). On the limitations of linguistics applied. Applied Linguistics, 21(1), 3–25.

Detong Xia, is a Ph.D. candidate in the Literacy and Second Language Studies Program at the University of Cincinnati. Her research focuses on corpus linguistics, L2 writing and ESP/EAP.

Hye K. Pae, Ph.D., is a Professor in the Literacy and Second Language Studies Program in the School of Education at the University of Cincinnati. She specializes in psycholinguistics and TESOL. |