Of special interest to teachers of "conversation" is students' ability to initiate and carry on a coherent, meaningful interaction. The ability to use conversational conventions (e.g., to get attention, nominate a topic, develop the topic, maintain the topic [Hatch, 1978], and exit a conversational interaction, as well as employ appropriate coherence devices/discourse markers) has been referred to as conversational competence (Bachman, 1990; Bachman & Palmer, 2010).

Despite the obvious relevance of conversational competence to learners of English, very little research has been conducted on the linguistic and interactional features that underlie this ability. Thus, though a substantial body of research is emerging on the development of pragmatic competence (Achiba, 2003; Kasper & Rose, 2002; Rose & Kasper, 2001), most research on English language learners' development has focused on grammatical competence. And until recently, the research on learners' pragmatic ability focused primarily on knowledge of (and ability to produce) single-turn speech acts appropriate to particular contexts. However, when speakers engage in interaction and are required to initiate and respond to actions such as greetings, tellings, and requests for information, it is clear that knowledge and the ability to produce appropriate actions at the sentence level is not enough. To engage in jointly constructed actions, they also need to be able to construct coherent spoken texts, an ability that is referred to as interactional competence (He & Young, 1998; Kasper & Rose, 2002; Markee, 2007).

In order to identify features of conversation and interaction that could be supported and perhaps developed in the classroom, researchers have begun to apply principles of conversation analysis (CA) to examinations of classroom interaction (Hellerman, 2008; Waring, 2008). CA is concerned with the organization of talk-in-interaction (not just conversation). It relies completely on naturally occurring data―videotaped and transcribed―with close attention to aspects of production. Analysis focuses on how a speaker's utterance is understood by the interlocutor (as indicated by the interlocutor's response), not by the analyst or a classroom teacher.

Conversation analysts take as basic a number of facts about conversation, including the following: (a) Speaker change recurs, or at least occurs; (b) Overwhelmingly one party talks at a time; and (c) Transitions from one turn to a next with no gap and no overlap are common. Together with transitions characterized by slight gap or slight overlap, they make up the vast majority of transitions (Sacks, Schegloff, & Jefferson, 1974). These facts hold across cultures, although details of turn structure (such as lengths of overlap and pauses) may vary.

A basic CA concept that is relevant for examining learner interaction is that of a transition relevance place (TRP), the end of a minimal syntactic unit expressing a complete thought. It is at or near a TRP that speaker change typically takes place. See Example 1 (invented for illustrative purposes), in which potential transition relevance places are marked with a slash (/).

|

Ex 1: |

A: |

Where are you going/after class/today?/ |

|

B: |

Home./ |

Speakers are usually vulnerable at TRPs; in other words, this is where another speaker may start speaking and in many cases is expected to do so (Jefferson, 1973). (Note that nonlinguistic features such as prosody and nonverbal gestures will influence whether an interlocutor does in fact begin to speak at any of these points.)

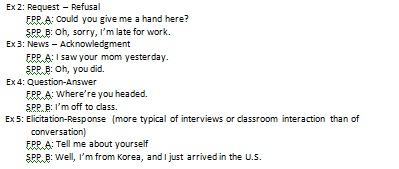

Sequences of talk are typically realized through a number of interactional acts. The basic sequence is the adjacency pair (AP), a pair of closely related turns. APs consist of two ordered utterances usually produced successively by different speakers. The initiating act, or first pair part (FPP), often selects the next action (and speaker)―it sets up expectations as to the nature of the next turn, the type of possible responsive actions. The response, or second pair part (SPP), is seen as fulfilling the expectation of the FPP. Examples 2 to 5 (invented for illustrative purposes) provide instances of APs.

Given that conversational/interactional competence is a goal of many English language learners, it is important to take note of some of the abilities that achievement of that goal may involve. Bachman's (1990, 2010) description of conversational competence suggests that learners should minimally be able to establish, maintain, and terminate an interaction (Bachman, 1990). In other words, they should be able to initiate an FPP that establishes a topic; respond to another's initiation with a coherent, topical SPP; and expand on or close down a topic.

Note that responding appropriately involves anticipating TRPs (i.e., taking a turn [or indicating a turn pass] at a TRP); timing turns (taking a turn immediately, with minimal overlap); and shaping the turn to reflect awareness of (and, in many cases, a stance toward) the prior speaker's turn.

CONTRASTING NATIVE SPEAKER AND LEARNER CONVERSATIONAL COMPETENCE

Teaching conversation is often accomplished by setting students in pairs and giving them a topic to discuss. Comparison of the conversational/interactional competence of an EFL learner and a native speaker performing the same "conversation" task offers an idea of what types of actions novice learners may enact in classroom "conversation" tasks. Examples 6 and 7 represent the opening sequences in a conversation task between low-proficiency learners and then between two native speakers of English. The conversations were produced by native speakers of English living in Japan and EFL university students (in Japan). Students were told to

Carry on a conversation in which you:

a. Introduce yourself to your partner

b. Exchange information about yourselves

As with many classroom conversation activities in which learners are instructed to elicit certain information or discuss a predetermined topic, this task does not result in a truly natural conversation, but rather in a more or less casual interview (see Mori, 2002, for discussion and analysis of a conversation/interview in a foreign language classroom).

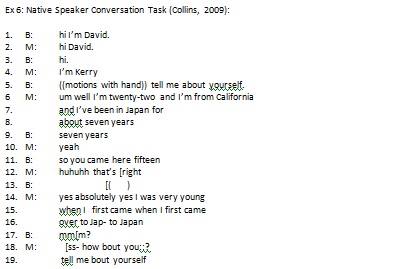

In Example 6, Merry and Benji (pseudonyms) greet each other.

Consider what the native speakers of English did in response to the task instructions. First of all, they produced a greeting-self-introduction sequence (lines 1-4), followed by elicitation (FPP line 5) and a response (SPP lines 6-8). The information in the responding turn was attended to with brief responses. The repetition in line 9 and the inference in line 11 were both regarded as repair initiators requiring confirmation, the second of which was treated as an opportunity for further elaboration (lines 14-16). In line 17, Benji bypassed an opportunity to take a turn with a brief response token (mmm,) and Merry took the opportunity to begin a reciprocal elicitation of personal information about Benji. Turns were relatively brief, with minimal interturn gap and some overlap. Turn-initial tokens such as well (line 6) and ss (so) (line 18) established coherence with the previous turn.

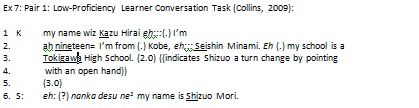

Example 7 provides an instance of two low-proficiency Japanese EFL learners, Kazu and Shizuo, beginning to introduce themselves in response to the same conversational prompt.

What did the learners do? The most salient aspect of the learner conversation is the long, monologic multi-unit turn with no response from the interlocutor. The conversation includes no greetings and no elicitations (e.g., "tell me about yourself"). Unlike the native speakers, learners introduce themselves with first and last names. Speakership is transferred by gesture, with no accompanying verbal elicitation. Overlap does not occur, and in fact large interturn gaps loom between speakers. Turn-initially, the speakers rely on their L1 or placeholders, rather than tokens reflecting stance, leaving little indication that a previous turn had even taken place, much less that the speaker was responding to or aligning with it in any way. No responses occur at TRPs―no repair initiations, no prompts for more information, no assessments. In sum, the amount of interaction is negligible.

THE CHALLENGE FOR LEARNERS AND TEACHERS

We can assume that the learners in Example 7 knew all the words and forms they needed (although the expression "my school is . . ." is collocationally unnatural, as natives would generally say "I go to X school"). So what is the problem? An obvious initial answer is that they need to develop fluency. This is undoubtedly true. Online processing requirements for producing a single new sentence can be overwhelming. However, conversation involves more than just the ability to produce a series of fluent utterances. It requires that conversationalists be aware of appropriate resources for beginning a sequence, establishing a topic, and relinquishing a turn. In addition, they need to be able to initiate FPPs and, more important, respond quickly to another's FPP. This involves projecting the TRP in the FPP at which a response is appropriate, launching into speech with a minimal interturn gap or using an appropriate response token to indicate a turn pass, and shaping the turn to reflect awareness of the prior speaker's turn (e.g., employing appropriate discourse markers indicating the speaker's relationship or stance toward the prior turn). It also requires the ability to indicate the speaker is about to construct a long (multi-unit) turn. Clearly, the students in Example 7 had not yet mastered these skills in the foreign language (although they were quite adept at using them in their L1).

The question for teachers is, How do learners develop interactional competence and how can teachers facilitate the process? More advanced Japanese EFL pairs in Collins's study reveal various degrees of facility elicitation, acknowledgment, and turntaking, with reactions to the information as it is supplied. The conversations with more interaction were conducted by students from the same class. These were students who in general exhibited more willingness to communicate and to attempt to use some of their knowledge of real interaction. However, as indicated by Example 7, not all students are able to apply their knowledge of conversation to this type of classroom task. For those learners other resources/activities can provide support for teachers who wish to aid learners' acquisition of these abilities. I provide a few examples here (several of which are useful for developing fluency as well):

- Guided exposure to natural conversation - especially examples of native speakers performing the same task/activity.

- Frequent opportunities to produce conversation.

- Recycling of opportunities to use idiomatic phrases and strategies in common interactions

- Audio- or videotapes of learners' own production for self-evaluation

- Activities designed to raise awareness and provide opportunities for practice such as those in Houck and Tatsuki (in press).

Clearly, there is no easy answer. However, with appropriate resources, teachers can speed up what can be a painstakingly slow process and provide students with a real sense of their developing competence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many thanks to Jean Wong for comments on an earlier draft.

REFERENCES

Achiba, M. (2003). Learning to request in a second language: A study of child interlanguage pragmatics. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Bachman, L. (1990). Fundamental considerations in language testing. Oxford, England: OxfordUniversity Press.

Bachman, L., & Palmer, A. (2010). Language assessment in practice: Developing language assessments and justifying their use in the real world. Oxford, England: OxfordUniversity Press.

Collins, B. (2009). Analysis of spoken discourse: Language ability differences in framed introductions. Unpublished manuscript.

Hatch, E. (1978). Discourse analysis and second language acquisition. In E. Hatch (Ed.), Second language acquisition (pp. 401-435). Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

He, A., & Young, R. (1998). Language proficiency interviews: A discourse approach. In R. Young & A. He (Eds.), Talking and testing. Discourse approaches to the assessment of oral proficiency (pp. 1-24). Amersterdam, The Netherlands: Benjamins.

Hellerman, J. (2008). Social actions for classroom learning. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Houck, N., & Tatsuki, D. (in press). Pragmatics: Teaching natural conversation. Washington, DC: TESOL.

Jefferson, G. (1973). A case of precision timing in ordinary conversation: Overlapped tag-positioned address terms in closing sequences . Semiotica, 9(1), 47-96.

Kasper, G., & Rose, K. (2002). Pragmatic development in a second language. Language Learning, 52 (Suppl. 1).

Markee, N. (2007). Invitation talk. In Z. Hua, P. Seedhouse, L. Wei, & V. Cook (Eds.), Language learning and teaching as social inter-action (pp. 42-57). New York, NY: Palgrave.

Mori, J. (2002). Task design, plan, and development of talk-in-interaction: An analysis of a small group activity in a Japanese language classroom. Applied Linguistics, 23, 323-347.

Rose, K., & Kasper, G. (2001). Pragmatics in language teaching. Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press.

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50, 696-735.

Waring, H. (2008). Using explicit positive assessment in the language classroom: IRF, feedback, and learning opportunities. The Modern Language Journal, 92(4), 577-594.