|

Tanya L. Erdelyi |

Virginia K. Gillenwater Kita |

The modal system is a challenging structure for ESL/EFL

learners (Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman, 1999; Master, 1996).

Difficulties experienced are attributable to the variety of forms and

multiplicity of meanings used to express modality. Modality in English

is typically expressed with modal auxiliaries, known simply as modals;

examples include should, must, might, etc. These

forms are divided into two categories: root (social obligation) and

epistemic (logical possibility). Meanings associated with the root modalshould are those of obligation, a sense of what one

is supposed to do. Epistemic meaning implies probability, what one

expects ought to occur (Master, 1996).

The natural order hypothesis of Krashen’s (1982) monitor theory

states that certain language features, such as modal forms, will be

acquired before others regardless of what is taught. Consequently,

manydevelopmental sequences(i.e., lists of ordered stages of

development) have been proposed. However, preexisting developmental

sequences for should have not been identified by

the researchers.

This article reports the results of a pilot study conducted with one

learner in her acquisition of the modal should. The

following research questions were investigated:

- How does the learner’s use of should during structured lessons differ from

performance in unstructured conversation?

- How does limited instruction impact use of should?

Ultimately, the researchers attempted to define a

developmental sequence of the learner’s acquisition of should.

METHODOLOGY

The learner, Emi, is a Japanese housewife who has studied

English with one of the researchers for 4 years, and has been studying

English informally for 40 years following her high school English

education. Emi has read many unedited versions of English language

novels. She has a sizeable vocabulary; however, she lacks speaking

fluency. For the study, Emi was asked what she would like to focus on.

She chose modals. Prior to the study, Emi was already using the modals should and have to; however, she

was aware of her errors with these forms and wanted to improve. This

study involved 10 one-hour weekly tutoring sessions, each divided

equally into two parts: free conversation and instruction. During free

conversation, the researcher did not explicitly encourage modal use;

however, questions such as “What should I do?” were used by the

researcher to create opportunities for such usage.

The instructional parts of the first two sessions assessed

Emi’s command of modals. Both researchers transcribed and verified all

occurrences of should. An analysis was done using 76

obligatory occasions of should that occurred across

all 10 sessions. Various ways Emi attempted to produce should were categorized and examined using frequency

analysis. Explicit instruction on modals for stating rules (e.g., “You

should do your homework”) was the focus of Sessions 3 and 4. In Sessions

5 through 10, modals for giving advice (e.g., “You should have a party

for your parents”)were taught and practiced using instructional

worksheets and role plays.

In Sessions 3 and 9, Emi studied the meanings of modals

(should, can, must, and have to),

the level of certainty each expresses, and the negated forms. Session 4

focused on modal sentence structure. Written homework was given in

Sessions 3 through 8, allowing Emi to prepare utterances beforehand.

These written utterances served as scaffolding during discussion-based

lessons (Ellis, 2008). In Sessions 9 and 10, Emi practiced forming

statements of rules and advice without advance writings.

RESULTS

Due to Emi’s frequent use of should, the

study centered on this modal. Emi used should and have to without prompting during free conversation in

Session 2, which shows some understanding of modal usage before

structured lessons began. She also used modals without prompting in

Sessions 6 and 7. However, during Sessions 5, 7, and 9, Emi missed

opportunities to use modals during free conversation, even with

prompting. It should be noted that the topic of conversation (e.g.,

giving advice about child-rearing) varied from session to session and

could have contributed to the frequency of modal production.

During structured Sessions 4 to 8, Emi showed a remarkable

ability to memorize and recite sentences prepared in her written

homework. In Session 8, she was asked to recall the rules from her

Session 3 homework and did so with only a few pauses and mistakes.

However, there was a considerable drop in proficiency when she was asked

to produce original statements in Sessions 5, 6, 9, and 10.

The obligatory occasion analysis of Table 1 shows a 43 percent

increase in the correct usage of should.

Table 1. Obligatory Occasion Analysis of Should

|

Session/Date |

Correct |

Total Number of

Occasions |

Percentage Correct |

|

2 09/14/11 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

10 11/09/11 |

3 |

7 |

43 |

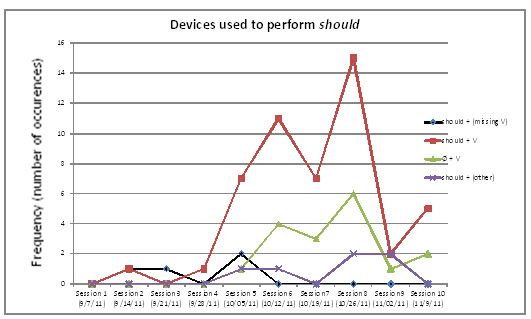

Figure 1 is a frequency analysis of all uses of should, divided into four categories. Other includes five subcategories: a) should with auxiliary and main verb; b) should with inflected verb; c) negative should with verb; d) negative should without verb; and e) should

with negative auxiliary verb and verb.

Figure 1 indicates most modals were produced during Sessions 5

through 8. Sessions 1 to 4 provided fewer opportunities to use modals

due to assessment and instruction. The last two sessions involved longer

role plays during which attention was not exclusively focused on modal

production.

Figure 1. Frequency Analysis of All Should Utterances (Errors After Verb Ignored)

DISCUSSION

Unfortunately, there was not enough data from the unstructured

portions of each session, as relatively few instances of should were produced. Despite expectations, the

paucity of data made a meaningful comparison of Emi’s should utterances in unstructured conversations difficult.

A tentative developmental sequence of this learner’s

acquisition of should is described below. The

sequence was derived from the frequency analysis; other researchers have

used a similar methodology for negation and interrogatives (Cancino,

Rosansky, & Schumann, 1978). We were unable to find a

well-established sequence of should in previous

research. However, from our data, we identified the following

sequence:

- should + (missing V)

- missing should + V

- should + V

Emi stopped producing should utterances with

a missing main verb by the sixth session. Thus, she seemingly

progressed out of stage one. The remaining two stages are more difficult

to define. At all times, Emi produced utterances in the form of should + V more frequently than the form “missing should + V” (i.e., not using should before a verb even though necessitated by the

meaning and/or context of the utterance). However, in Sessions 5 through

10, Emi produced both forms. There was never a period in which she

favored missing should + V phrases over

should + V. Missing should + V was compared

with should + V utterances: in Session 5, there were

six more should + V utterances than missing should + V utterances; in Session 10, there were

three more; in Session 9, there was only one more. This unexpected

result is more striking considering that in Session 7, Emi left out should more often than she correctly produced should in clauses that were also correct. One might

have expected the opposite. It appears that, even though Emi correctly

used should more frequently by the end, she also

omitted should (as in missing should + V utterances) quite frequently.

Just as Emi’s knowledge of basic sentence structure seemed to

falter with the introduction of modals, production of correct should + V phrases may adversely affect remaining

portions of her clauses. One explanation is that the increase in other

errors is due to added cognitive demand about which modal to use

(Cummins, 1982). Perhaps another is lack of planning time to attend to

form and meaning aspects of the modal and other parts of the clauses

(Skehan, 1998).

CONCLUSION

Clearly, more work is needed to achieve conclusive results. It

was beyond the scope of this project to investigate modals other than should. Likewise, the effect of the topic of

conversation on the frequency of modals production was not examined.

Follow-up with Emi’s development of the modal should is planned. It will be interesting to see when she begins to

consistently produce appropriate should + V structures. The developmental sequence outlined above cannot

be generalized to other learners. However, it is possible that this

sequence could serve as a starting point for continued study.

REFERENCES

Cancino, H., Rosansky, E., & Schumann, J. (1978). The

acquisition of English negatives and interrogatives by native speakers.

In E. Hatch (Ed.), Second language

acquisition (pp. 207-230). Rowley, MA: Newbury

House.

Celce-Murcia, M., & Larsen-Freeman, D. (1999). The grammar book. Boston, MA: Heinle, Cengage

Learning.

Cummins, J. (1982). Tests, achievement, and bilingual students.Focus, 9, 2-9.

Ellis, R. (2008). The study of second language

acquisition. Oxford, England: Oxford University

Press.

Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and practice in second

language acquisition. Oxford, England: Pergamon.

Master, P. (1996). Systems in English grammar: An

introduction for language teachers. Upper Saddle River, NJ:

Prentice Hall Regents.

Skehan, P. (1998). A cognitive approach to language

learning. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. |