|

Task-based instruction (TBI), when applied according to a

cycle, can turn regular language learning activities into meaningful

practice of real life scenarios. In Canada, the nation-wide Language

Instruction for Newcomers to Canada (LINC) program, which follows the

Canadian Language Benchmarks (CLB), has its curricula centered on 12

levels of “communicative competencies and performance tasks through

which learners demonstrate application of language knowledge (i.e.,

competence) and skill (i.e., ability)” (Centre for Canadian Language

Benchmarks, 2012, p. v). As tasks are central to the CLB, this

presentation will show how a simplified, pragmatic form of TBI can be

incorporated into the classroom, both within a LINC context and

beyond.

Task is a term that has relevance in the

real world; therefore, finding a suitable definition for the language

classroom is key. Three relevant explanations of task

include the following: the CLB defines a language task as “a

communicative ‘real world’ instance of language use to accomplish a

specific purpose in a particular context” (Centre for Canadian Language

Benchmarks, 2012, p. ix); Nunan (2004) defines a pedagogical task as

a piece of classroom work that involves learners in

comprehending, manipulating, producing or interacting in the target

language while their attention is focused on mobilizing their

grammatical knowledge in order to express meaning, and in which the

intention is to convey meaning rather than to manipulate form. (p.

4)

Willis (1996) defines a task as an activity “where the target

language is used by the learner for a communicative purpose (goal) in

order to achieve an outcome” (p. 23). These three takes on task give subtle nuances to better understand how to

approach tasks in the language classroom.

A common theme in TBI is that tasks allow for learners to

engage in meaningful/purposeful activities using the inventory of

language they already possess, exploiting what they already know, rather

than following what could be described as prescribed, overly rehearsed

target forms. In programs where real-world communication is the target,

such as the LINC program, using a TBI model is a logical approach.

However, some teachers believe the focus of the English-language

classroom should be discrete language forms (e.g., vocabulary lists,

grammar rules, and extended pronunciation practice). I believe that

teachers can easily incorporate TBI models/methodologies and adapt their

teaching practices to have tasks as the focal point of the lessons,

with language focus as a follow-up that further supports successful

completion of target tasks. For example, a task related to an audio

recording of a weather report could have students planning what to wear

or activities to do. The communicative task reflects what we normally do

with weather reports in the real world. Follow-up language focus might

include weather vocabulary, typical structure of weather reports, or

listening to and understanding numbers.

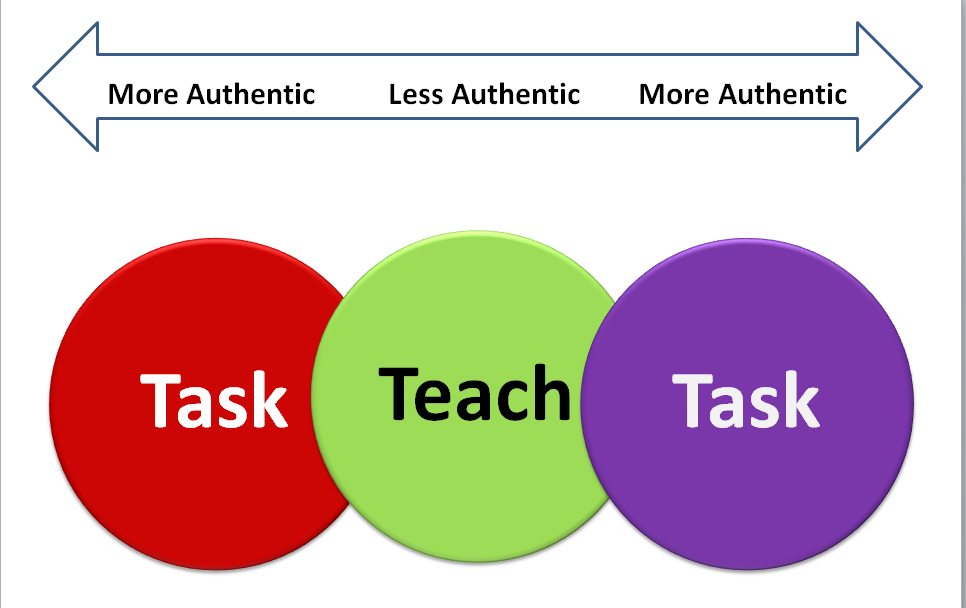

Willis (1996), Ellis (2003), and Nunan (2004) provide

well-known frameworks for TBI, and these will be reviewed in the

presentation. Nonetheless, as a result of extensive discussion with LINC

instructors, my colleague and I devised a simplified TBI framework:

Task-Teach-Task (Rockwell & Williams, 2014). In this model (see

Figure 1), similar to the aforementioned frameworks, we encourage

teachers to lead in with the first “Task” for diagnostic and learner

self-assessment purposes. The students’ level of success in doing the

task then allows the instructor to determine which elements should be

included in the “Teach” (i.e., language focus) phase to ensure more

successful completion of the same or similar task. Finally, the teacher

ends the cycle with a final “Task” phase, using the same or a similar

task, to check if the task is completed more successfully and to give

students tangible evidence of their learning. For example, the teacher

may ask the students to write an email to their child’s teacher thanking

them for coaching the basketball team. Students’ achievement of the

task would determine what language needs development in the “Teach”

phase, such as appropriate subject lines, salutations, formatting of the

email message. To complete the cycle, in the final “Task” phase, the

students might be asked to do a similar task—sending a thank you email

to a neighbor for watering the garden—to assess if the learning

objectives were met. The Task-Teach-Task framework is not indicative of a

cycle that would be covered within one lesson, but a cycle that would

be completed over a series of lessons.

Figure 1: Task-Teach-Task Framework

In TBI, assessment is

embedded in the teaching cycle and it will inevitably be a “direct

assessment” (Ellis, 2003; Nunan, 2004) approach. In other words,

assessment is directly related to the “communicative behaviors

[learners] will need to carry out in the real world” (Nunan, 2004, p.

139). In Task-Teach-Task, the intention is for the first Task to include

learner self-assessment and teacher’s diagnostic assessment to

determine the focus of the Teach phase. The final Task phase ideally

includes a formal assessment, as a “check” for that particular task as

it relates to a competency or learning outcome. What is not assessed in

this framework, however, are discrete language points. A task is

assessed within the framework of a set context and set criteria: Is the

task achieved, and, what are the indicators of success? While a target

task is based on a real-world task, the criteria for success must be

calibrated for the learners’ level. While the eventual target competency

might be a fluent, proficient speaker’s approach to a similar task,

task assessment must be aligned to the outcomes for a particular level.

Both Ellis (2003) and Nunan (2004) provide caveats that TBI is

not interchangeable with task-based assessment as assessment contexts

allow for less teacher flexibility; in other words, when tasks are the

basis for assessment, it is important that there are clear “criteria for

assessing learner performance” (Nunan, p. 164) in order to adhere to

reliability and validity as much as possible. While there are some

issues with task-based assessment, both Ellis (2003) and Nunan (2004)

agree formative assessment is an important part of TBI. Indeed,

assessment for learning is embedded in Task-Teach-Task. For example, in

the aforementioned thank-you email, when used as an assessment task, the

students would have had prior practice writing emails, knowing what the

important elements are, and they would know prior to the assessment

task, what indicators or criteria will be measured.

In conclusion, the classroom and the “real world” can be

bridged by ensuring the classroom is based on pedagogical tasks (modeled

on real world tasks) and the teacher provides a context where learners

can experiment with the language skills they already have to negotiate

completion of a variety of tasks. In the task-based classroom, language

focus is not ignored at the expense of practicing real-life scenarios,

but supplements successful achievement of tasks. Further, assessment is

not relegated to decontextualized language focus, but is directly

related to the criteria needed for successful completion of the task.

Finally, when real-world tasks are the focal point of the language

classroom, a bridge naturally emerges, where classroom success might

easily translate to success in “real life.”

REFERENCES

Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks. (2012). Canadian

language benchmarks: English as a second language for adults. Ottawa,

ON: Author.

Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based language learning and

teaching. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Nunan, D. (2004). Task-based language

teaching. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University

Press.

Rockwell, K., & Williams, S. (2014, July).

Task-Teach-Task. MOSAIC PD Day. Paper presented at

North Shore Multicultural Society, North Vancouver, BC,

Canada.

Willis, J. (1996). A

framework for task-based learning. Retrieved from http://www.intrinsicbooks.co.uk/titles/methodology/index.html.

Shawna Williams has a Master’s of Education from the

University of British Columbia. She is a provincial instructional

resource coordinator with the Language Instruction Support and Training

Network in British Columbia, Canada, where she works with instructors

across British Columbia engaged in settlement-language teaching in the

Language Instruction for Newcomers to Canada Program. She is also the

president of the BC Association of Teachers of English as an Additional

Language (BC TEAL), an affiliate of TESOL

International. |