|

Charlotte Nolen

|

|

YouJin Kim

|

Pedagogical tasks (PTs) have been increasingly used in language classrooms to prepare learners for successful target task completion in task-based language teaching (TBLT). To what extent learners can transfer their skills developed during task performance to the subsequent new tasks (i.e., transferability) has become identified as a real issue in TBLT research (Long, 2016; Ellis, 2017). There is little to no systematic documentation of task transferability when learners leave the classroom and use learned skills to accomplish real-world tasks (RWTs) out in the local community (Long, 2016). The current exploratory study examined to what extent learners use and discuss the meaning and form of target vocabulary during PTs and RWTs.

Theoretical Framework

Long (2016) states, “Tasks are the real-world communicative uses to which learners will put the L2 [second language] beyond the classroom- the things they will do in and through L2” (p. 6). Real-world (also referred to as “primary” or “target”) tasks can be something like filling out a job application. Long (2016) adds that in previous classroom or laboratory studies, PTs prepare learners to accomplish RWTs. RWTs are used to determine a task-based syllabus, which structures the sequencing of PTs. Little is known about how far learners are able to transfer their task performance skills from one task to the other (Long, 2016).

In the current multi-case study, we examined task-based vocabulary acquisition and learners’ ability to transfer their vocabulary use during PTs to RWTs. We calculated word frequencies (i.e., how often target vocabulary is used) and the number of language-related episodes involving target words (i.e., how much meaning and form is negotiated) to investigate vocabulary use and the degree of learners’ attention to vocabulary (Swain & Lapkin, 1998).

Research Questions

-

To what extent do learners use and discuss target words during PTs and RWTs?

-

What do learners think about the effectiveness of PTs preparing them to accomplish RWTs?

Methods

Three adult learners participated in the study: David (a 36-year-old advanced-mid male speaker), Susan (a 30-year-old advanced-low female speaker), and Edward (a 28-year-old intermediate-high male speaker). The study was conducted in a private nonprofit study abroad program in the United States. The participants attend English as a second language classes from Monday to Friday for 4 hours a day with independent study assignments in the afternoons. They were also required to attend weekly in-community field trip on Fridays. The real-world context (from the field trips) was the focus for RWT completion in this study.

This study focused on two content-based units as a part of in-community field trips, the Civil Rights Movement and U.S. War History, both in the United States (see Table 1). The research follows a pretest-posttest design evaluating vocabulary acquisition. Target vocabulary words were chosen from domain site content (e.g., brochures, displays, and monuments) collected on visits to two museums made by the instructor prior to the TBLT units. Unit 1 consisted of 24 target words (e.g., segregation, brutalities) and Unit 2 contained 20 words (e.g., adversity, battle-scarred).

Table 1. Study Design Including Pedagogical (Classroom) and Real-World (Field Trips) Tasks

|

Day |

Task |

Unit 1:Civil Rights

Movement |

Unit 2: U.S. War History |

|

1 |

Pretest and interview |

Pretest and interview |

Pretest and interview |

|

2 |

PT 1 |

Information gap and timeline task |

Information gap and timeline task |

|

3 |

PT 2 |

Video documentary listening task |

Military branch presentation task |

|

4 |

PT 3 |

Role-play task |

Role-play task |

|

8 |

RWT 1 |

Interview with three African Americans |

Tour and interactive conversation at the War Veterans Museum |

|

9 |

RWT 2 |

Interview with a

White man |

Interview with a young war veteran |

|

10 |

Posttest and exit interview |

Pretest and interview |

Posttest and exit interview |

The study was conducted over 4 weeks (2 weeks in each unit). For both units, learners completed a pretest, three PTs (60 minutes each) in the classroom, two RWTs (90 minutes each) in the local community, and a posttest (see Table 1). The PTs were largely focused task types moving from input- to output-based tasks about the topic of the unit, and the RWTs required learners to interview native speakers with different backgrounds about the topics using the input materials available at the museums. Following Robinson’s (2011) triadic framework, we sequenced our tasks based on complexity using +/- open solutions (i.e., determinate vs. indeterminate; clear resolvable interactions). The PTs in this study have more determined outcomes, and RWTs have more open outcomes. The same procedure was repeated for the two units. Target vocabulary items were incorporated during PTs; however, they were not provided during RWTs. Vocabulary tests were oral and written production picture description tests that required learners to describe the scenes. Vocabulary tests and semi-structured interviews about student perceptions toward PTs and RWTs were conducted prior to and upon completion of the units.

To examine the transferability of vocabulary use between PTs and RWTs, we examined students’ use and discussion of target words. We audio-recorded students’ task performance and measured their vocabulary use and discussion of vocabulary words using the frequency of the occurrence of words and the number of language-related episodes (LREs), which is defined as an episode in which learners discuss meaning or form of target words.

In terms of measuring vocabulary learning, we gave one point to the correct target word use (i.e., a possible 24 points in Unit 1 on oral tests and 20 points in Unit 2 on written tests). Also, we used a gradated rubric for RWT completion, marked as complete, partially complete, or incomplete. All three learners earned “complete” in the RWTs in this project.

Findings

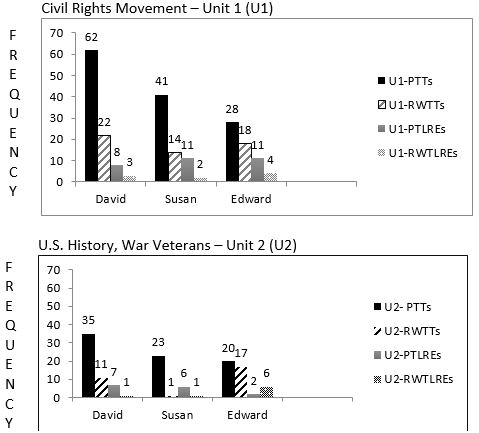

There were more target words used (tokens) and more LREs in PTs than in RWTs in oral performance. This pattern occurred in both units (See Figure 1). Overall David and Susan (upper level speakers) used more target words and had more LREs in PTs, while Edward (lower level speaker) used more target words and had more LREs in RWTs.

Note: PTT = pedagogical task token (target words produced during pedagogical tasks), RWTT = real-world task token (target words produced during real-world tasks). PTLREs=pedagogical task language related episodes (LREs produced during pedagogical tasks), RWTLRE = real-world task language-related episode (LREs produced during real-world tasks),

Figure 1. Recorded target vocabulary use (tokens) and language-related episodes.

Following are the participants’ pre- and posttest examined vocabulary learning percentage scores:

-

David: Unit 1 pretest/posttest scores: 0.27/0.92; Unit 2 pretest/posttest scores: 0.33/1.00

-

Susan: Unit 1 pretest/posttest scores: 0.19/0.92; Unit 2 pretest/posttest scores: 0.38/0.98

-

Edward: Unit 1 pretest/ posttest scores: 0.25/0.92; Unit 2 pretest/posttest scores: 0.100/0.88

Posttest scores suggest that immediate vocabulary learning occurred after the task performance. However, delayed learning effect was not confirmed because of a lack of delayed posttests.

In post interviews, all three learners expressed that the PTs helped prepare them to accomplish the RWTs, though task types varied between the classroom and real-world contexts. Native speakers that David and Susan (upper levellearners) interacted with were very talkative and used many target words (facilitating receptive language skills). David and Susan were concerned with pragmatic issues (e.g., interrupting older guests, making requests) while Edward, the lower level learner, was predominantly concerned with using fluid speech and delivering clear messages. This suggests why both David and Susan produced a lot fewer target words during RWTs compared to Edward.

Conclusion

This was an exploratory multi-case study examining vocabulary acquisition during two TBLT units. One main implication of the study is how far the pattern of producing and negotiating for target words during PTs can be transferred to RWTs. Because David and Susan produced more target words during PTs and completed the RWTs successfully, this suggests that comprehension of target words might have occurred during PTs for the upper level learners. However, the results also suggest that learners struggle with prompt oral production during RWTs (on field trips), and further exploration of this in future research is needed. Edward, the lower level learner, used and discussed the meaning of target words more in RWTs, which suggests that he was still striving for mastery of production and meaning of some target words. This shows some transfer of production and negotiating words in RWTs by Edward.

Because of several unpredictable factors in real-world language use in public contexts (e.g., talkative guides), practitioners might consider adding unpredictable variables during PT completion (e.g., excessive talking in a role-play that allows learners to practice polite interruptions) or providing domain site experts with some orientation as to the learners’ RWT goals. Finally, learners reported that PTs prepared them for the public domain sites, and such perception became increasingly more positive over the course of studying the two units.

References

Ellis, R. (2017). Position paper: Moving task-based language teaching forward. Language Teaching, 50(4), 507–526.

Long, M. H. (2016). In defense of tasks and TBLT: Nonissues and real issues. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 36, 5–33.

Robinson, P. (Ed.). (2011). Second language task complexity: Researching the cognition hypothesis of language learning and performance (Vol. 2). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Swain, M., & Lapkin S. (1998). Interaction and second language learning: Two adolescent French immersion students working together. Modern Language Journal, 82(3), 320–337. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb01209.x

Charlotte Nolen is currently a PhD student in applied linguistics at Georgia State University.

Dr. YouJin Kim is an associate professor in the Department of Applied Linguistics at Georgia State University. |