|

Content literacy has a direct impact on student academic

achievement. It is required of all students in the Common Core State

Standards. It is not an automatic development stemming from the learning

of content knowledge for all students. English learners (ELs), in

particular, need additional support to build up the content literacy

skills necessary for their academic success.

It has been well recognized that literacy instruction for ELs

should go beyond the level of academic vocabulary. Being able to

recognize and identify how a text is organized is pivotal for reading

content texts with understanding (Fang & Schleppegrell, 2008;

Williams, 2003) as well as writing academic discourse with clarity. This

article offers an approach to text structure instruction based on Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL), a semantic-functional approach to

text analysis. I first explain the main tenets of an SFL analysis of

text structure with illustrative examples drawn from K–12 textbooks and

teaching materials, and then I provide a set of instructional strategies

to teach text structure to ELs to support their content literacy

development.

Systemic Functional Linguistics Analysis of Text Structure

SFL has been used to identify the meaning-making linguistic

features of spoken and written texts of different genres for the purpose

of teaching students to read more efficiently. SFL takes the clause as a

base unit for analysis. Through an analysis of clauses in a text, it

looks for three meaning-making mechanisms that work simultaneously in a

text: textual meaning (how the text is organized), experiential meaning

(what the text is about), and interpersonal meaning (what the author’s

perspective is and how it is expressed; Fang & Schleppegrell,

2008). An understanding of how a text is organized contributes to an

understanding of the key ideas of a text and how details are put

together to support the key ideas.

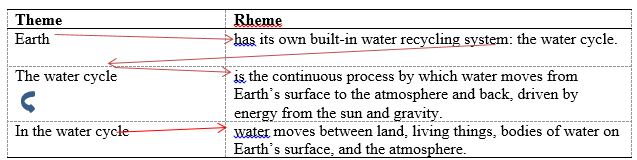

To reveal the textual meaning of a text, SFL divides a clause

into two meaning-making parts: theme and rheme. Theme is “a particular departure point” of a

clause, and rheme is what has been presented as “something new” (Fang

& Schleppegrell, 2008, p. 11). As illustrated in Table 1, a

theme can be the subject, and a rheme can be the predicate, but theyare

not to be taken as synonymous with the more familiar terms of subject and predicate.

Table 1. Theme-Rheme Analysis of Clauses in Content Texts

|

Content Area |

Theme |

Rheme |

Sources |

|

Science |

In the water cycle, |

water moves between land, living

things, bodies of water on Earth’s surface, and the

atmosphere. |

Hart (2005) |

|

History |

White settlers |

had come into conflict with Native Americans |

Buckley, Miller, Padilla, Thornton, & Wysession (2014) |

A text is then organized around the theme and rheme of clauses.

Much like a weaver weaving a pattern with a shuttle and threads, the

thememoves a text from beginning to end and the rheme supplies the exact

information. Different texts, of course, adopt different theme-rheme

systems. For instance, a chronicling history text is typically marked by

themes of prepositional phrases and adverbs of time, place, and manner,

such as “in 1776, in Boston,” and “in this way.” Science texts,

however, tend to use the reiteration of themes and the zig-zagging

pattern of themes and rhemes to provide information and convey complex

ideas. Such theme-rheme patterning creates a coherent and cohesive text,

as illustrated in Figure 1, where the reiteration of themes is marked

by the curved arrows and the zig-zag patterning by the straight arrows.

Figure 1. Theme-rheme patterning in a science text.

Click to enlarge.

Of particular interest is that the zig-zagging patterning of

theme and rheme in different content texts serves different text

functions. For instance, when the pattern is used in science texts, it

often offers further explanation or details of a phenomenon. As

illustrated in the first two sentences in Figure 1, the ending phrase of

the first sentence, “the water cycle,” becomes the theme of the second

sentence, which gives a definition of what the water cycle is in its

rheme, “is the continuous process by which water moves from Earth’s

surface to the atmosphere and back, driven by energy from the sun and

gravity.”

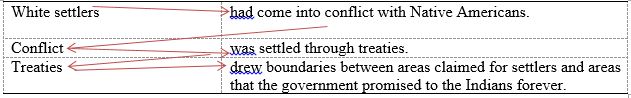

The theme-rheme pattern in a history text may be used to

explain the cause-and-effect of a historic event rather than offering

further explanation or details. An example is shown in Figure 2 with a

passage from Hart (2005) that explains how the American Indian

Reservations came about.

Figure 2. Zig-zagging patterning in a history text.

Click to enlarge.

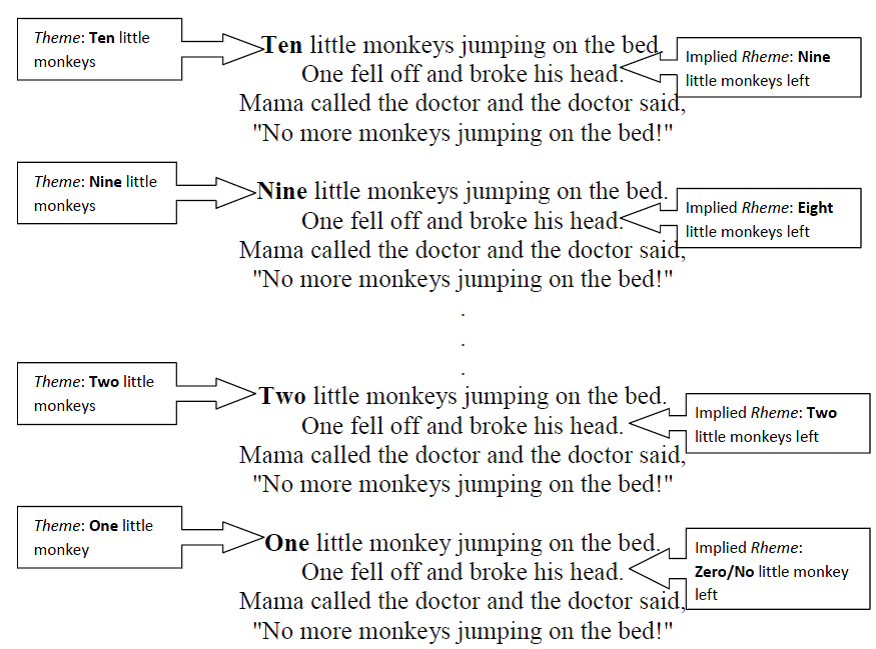

Though not as commonly found, the zig-zagging theme-rheme

pattern is also used in poems as threads of thoughts. An intriguing

example is shown in the nursery rhyme “Ten Little Monkeys Jumping on the

Bed,” where the zig-zagging pattern signals the development of the

story with implied rhemes, as annotated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Zig-zagging patterning in a nursery rhyme.

Click to enlarge.

The content text examples and their theme-rheme analysis in

this section demonstrates that understanding the theme-rheme structure

of a text is key to understanding how the organization of clauses in a

text makes a text meaningful. It offers a vantage point and the big

picture of a text for students to seek more information and meaning. As

text cohesion-building tools, theme and rheme are worthy access points

for in-depth comprehension of content texts.

Strategies to Teach Text Structure

Explicit instruction of text structure requires mindful

planning and strategic delivery. An instructional model that works well

with students is the Gradual Release of Responsibility (GRR)model, which

specifies four instructional steps:

1) I do it

2) We do it together

3) You do it together

4) You do it on your own (Fisher & Frey, 2013)

To teach the theme-rheme structure of texts, a teacher should

choose passages from the textbook or required readings that are similar

in complexity and organization to typical content-area texts. A

full-fledged lesson will use three passages (a model passage, a practice

passage, and a target passage) with instruction delivered following an

adapted GRR model that is recursive, as outlined in the Table 2. A

teacher, however, should be flexible in deciding whether to deliver all

steps in one class or spread them out into small sections through the

duration of teaching a particular content text. A teacher can also

relabel the technical terms of Theme and Rheme with beginning ideas and ending ideas should the teacher feel that students

would be more receptive to the relabeled terms.

Table 2. Theme-Rheme Structure Instruction Following the GRR Model

|

GRR Model |

Theme-Rheme Structure Instruction |

|

I Do It |

Demonstrate dividing at least three

clauses from the model passage into theme and

rheme. |

|

We Do It Together |

Together, divide the remaining

clauses in the model passage into theme and rheme. |

|

You Do It Together |

Ask students to work in pairs or

small groups to read the target passage first and then divide the

practice passage into theme and rheme. |

|

I Do It

+

We Do It Together |

Go back to the model passage and mark

the relationship between each theme and rheme using arrows as

illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 or similar marking systems, verbally

pointing out how meaning connects from one clause to another and

inviting students to join in the think aloud by asking questions or spot

checking. |

|

You Do It Together |

Ask students to mark the relationship

between each theme and rheme in the practice passage and verbally point

out the meaning relationships from one clause to another before sharing

the teacher’s own marking of the practice passage. |

|

You Do It on Your Own |

Give students the target passage to

practice and check comprehension with questions at the

end. |

As an ending thought, teachers should be aware that skill

building is a process that takes more than one practice and more than

the effort of a single teacher. The optimal scenario is for teachers of

ELs to collaborate in the planning and delivering of instruction of

content literacy to ensure consistency and strength of literacy

instruction. SFL might be a nontraditional approach to literacy

instruction, but given its strength in genre analysis and its linguistic

focus, it could offer an effective instruction solution to teachers of

both ELs and non-ELs who need additional support in developing the

necessary literacy skills to succeed academically.

References

Fang, Z., & Schleppegrell, M. J. ( 2008). Reading in secondary content areas: A language-based

pedagogy. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan

Press.

Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2013). Better learning

through structured teaching: A framework for the graduate release of

responsibility (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association for

Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Hart, D. (2005). History alive: The United States

through industrialism. Palo Alto, CA: Teachers’ Curriculum

Institute.

Buckley, D., Miller, Z., Padilla, M. J., Thornton, K.,

& Wysession, M. E. (2014). Interactive science: Science and

technology. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Williams, J. P. (2003). Teaching text structure to improve

reading comprehension. In H. L. Swanson, K. R. Harris, & S.

Graham (Eds.), Handbook of learning disabilities

(pp. 293–305). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Wei Zhang, PhD, is associate professor of linguistics and TESOL at the University of Akron. Her research focuses

on English learners’ disciplinary literacy development, TESOL teacher

training, and TESOL program design. |