|

Introduction

The corpus approach to researching the features and patterns of

language benefits English language teachers and TESOL practitioners as

they facilitate the learning and acquisition of English. Over the years,

the number of teachers incorporating corpus-based materials in their

classrooms has grown exponentially; yet, there still are relevant

teacher-related hurdles, including, in general, a lack of confidence in

the approach, time constraints, difficulty learning to use and access

tools, recurring questions of relevance, and the challenges in orienting

students and re-designing courses to integrate corpus tools and

corpus-based activities.

Corpus linguistics is primarily a methodological approach to

the study of language structure, patterns, and use. Exploring corpora

has become a popular approach in the quantitative analysis of the

linguistic characteristics of written and spoken discourse, resulting in

the development of more accurate teaching materials and frequency-based

dictionaries and ESL textbooks, especially for university-level

learners of English (Friginal, 2018). Corpora (singular form corpus) are, in a sense, datasets of systematically

collected, naturally-occurring language stored and processed in computer

platforms.

The four main characteristics of a corpus are that it is (1)

authentic, (2) relatively large, (3) electronic, and (4) conforms to

specific criteria (Bowker & Pearson, 2002). There are corpora

containing a variety of registers, also referred to as text

types, including academic English, spoken English, newspaper

articles, novels and short stories, or legal cases. There is no

particular rule regarding the size of a corpus, but it should be large

enough to allow a systematic analysis of relevant, target linguistic

patterns. With the advent of personal computers, as well as major

innovations on the internet, corpora have been freely shared and

analyzed predominantly for research purposes, but also increasingly for

pedagogy. One obvious benefit of this approach is that corpora allow for

the observation and study of real-world language use, with relevant

frequency distributions and access to actual occurrences of features,

rather than relying only on limited teacher or learner intuition.

Considering its potential, it is easy to envision the utility and

benefit of corpus-based approaches in a variety of teaching contexts

(Friginal, Dye, & Nolen, in press).

Theory to Practice: Corpora, Instructional Technology, and Data-Driven Learning

Direct applications of corpora and corpus tools in the

classroom support various language teaching and language acquisition

theories and concepts, especially related to learner autonomy, use of realia and authentic texts, the utility of

leaner-computer and learner-learner interactions, and explicit teaching

of language features and patterns. In the broader field of English

teaching across learners and contexts, corpora and corpus tools have

been incorporated into three primary instructional approaches: (1)

educational or instructional technology-based learning, (2)

computer-assisted language learning (CALL), and (3) data-driven learning

(DDL). These three strategies, especially the first two, share common

characteristics: both are machine-specific (i.e., computers) and they

also align well with and support other instructional approaches such as

learner-centered instruction or autonomous learning.

Specifically, DDL focuses on learners’ direct discovery and use

of linguistic information/data in the language classroom and beyond.

DDL allows learners to inductively discover language structures and

patterns through interacting actively with corpus software (e.g., a

concordancer) and personalized instructional materials. With this, DDL

presents learners with authentic language that centers literally on a

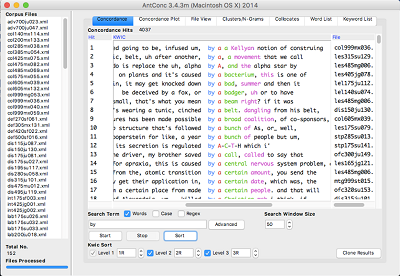

particular word or phrase (as shown in Figure 1). Concordancers may

provide users with the organized contexts of items that are searched,

allowing learners to explore the words before and after a given word. At

the same time, concordancers provide the immediate context surrounding a

target word or phrase, and this context is placed on the word or phrase

of interest leading to potentially discovering the meaning of the

sentence or paragraph as a whole (Friginal, Dye, & Nolen, in press).

Figure 1. Sample concordance output for the phrase “by a” and

common collocates using AntConc

(https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software/antconc/)

Research: How Effective Are Corpus-Based Approaches in TESOL?

Corpora have been put to practical use, especially in the

writing classroom, as described in a number of studies since the

mid-2000s. Freely available corpus databases such as the Corpus of

Contemporary American English (COCA) or the Michigan Corpus of

Upper-Level Student Papers (MICUSP) are easily accessible online. In the

field of TESOL, many of these studies highlight the classroom

experiences of non-native speakers (NNS) of English. A great deal of

linguistic variation exists across academic disciplines, and this can be

particularly challenging for NNSs working to improve their writing

within a specific field. Lee and Swales (2006) designed an experimental

course entitled “Exploring Your Own Discourse World” to help

international doctoral students in the U.S. compare their own writing to

that of more established writers in their fields. The students were

able to examine the use of linguistic elements like common verbs and

their conjugations, definite article usage, and collocates used in their

disciplines.

By comparing their own writing to those of experts, students

can identify, refine, and adapt their linguistic choices enabling

themselves to enhance their overall written presentation of ideas and

research processes. The benefit of acquiring this skill is that students

can continue to use the approach more independently and universally,

well after a course or workshop has finished. For example, Gilquin,

Granger, and Paquot (2007) examined the effectiveness of using NNS

learner corpora in conjunction with native corpora in an English for

Academic Purposes (EAP) context. They found the approach to be useful in

expanding NNSs’ linguistic repertoire and in avoiding falling into

common writing traps that many NNSs face (e.g., repetitive use of

transition words and phrases). In Friginal’s (2018) university-level Writing in Forestry course, students used corpus

tools to focus on developing their research report writing skills by

analyzing the distribution of specific linguistic features such as

linking adverbials, reporting verbs, verb tenses, and passive sentence

structures. The results of the study showed improvements in the

students’ report writing abilities after the corpus instruction.

Overall, research continues to show a great deal of enthusiasm from

teachers regarding corpus use, and there are some data, although still

limited, showing that university-level learners also tend to respond

positively to these types of corpus-based courses and approaches.

Conclusion: Doing What Works

In general, teachers who articulate a clear and immediate

academic English-related goals for their students and those confident in

the use of various types of software for teaching and academic

research, have developed a major interest for the corpus approach. They

typically find various meaningful opportunities to utilize data from

corpora in the classroom and beyond (Friginal, 2018). Applying corpus

tools in English instruction, thus, came naturally, and many teachers

find the approach to be exciting, creative, and fun for themselves and

their students. Clearly, however, there still are major limitations and

the corpus approach is not universally-applicable across TESOL contexts.

What works, then, based on current research on teacher perspectives and

experiences (see Friginal, 2018 and Friginal et al., in press for a more

detailed discussion) are intangibles such as the following themes

below:

Sufficient Teacher Preparation and Ample Time

To effectively introduce students to corpus tools requires

sufficient time for explanation, demonstration, and practice. Several

hours of class time will have to be committed exclusively for this

purpose. Depending on the teacher’s goals, different elements will

require varying amounts of time. The most basic aspects of concordancers

and online corpus databases could be introduced within a single class,

but if the students are expected to compile their own corpora to be

analyzed, more time will have to be allotted. Multiple opportunities to

practice using corpus tools are needed.

Sufficient Explanation of Merits and Limitations

Most learners will intuitively discover the benefits and

applications of this approach as they progress further into their

learning, but one of the most challenging initial responsibilities of

the teacher (to get students to fully commit) is to properly and

convincingly explain to students why these tools can be helpful. Focus

and commitment to learning the process are needed so students can

understand why their time is being spent on an initially difficult or

complicated set of instructions. Successfully explaining why concepts

like frequency, rarity, or authenticity of texts are valuable in

learning English or specifically in writing or editing their own papers

is certainly critical. Without appropriate explanation, it would be easy

for students to feel resentful, bored, or overwhelmed.

Appropriate (English) Language Level of Proficiency of Learners

The students need to have a sufficiently strong foundation of

English before setting out to analyze millions of words of text for

specific linguistic features such as linking adverbials or collocations.

Otherwise, they may not know what features to search for or how to

interpret the results. For this reason, it is recommended that these

types of courses be designed for at least intermediate students, but

preferably more advanced learners.

Relevant Learner Goals and Access to Tools and Materials

Students’ desired outcomes should relate specifically to the

instruction and learning contexts. Easy access to corpora, computer

labs, the internet, and related materials will have to be part of the

classroom routine and setting. A speaking or listening course could

incorporate corpora, but may not be as suitable as a vocabulary/grammar

and writing course. It would also be helpful if the students are at

least minimally computer literate.

References

Bowker, L., & Pearson, J. (2002). Working with

specialized language: A practical guide to using corpora. New

York, NY: Routledge.

Friginal, E. (2018). Corpus linguistics for English

teachers: New tools, online resources, and classroom

activities. New York, NY: Routledge.

Friginal, E., Dye, P., & Nolen, M. (in press).

Corpus-based approaches in language teaching: Outcomes, observations,

and teacher perspectives. Boğaziçi University Journal of

Education.

Gilquin, G., Granger, S., & Paquot, M. (2007). Learner

corpora: The missing link in EAP pedagogy. Journal of English

for Academic Purposes, 6(4), 319–335.

Lee, D., & Swales, J. (2006). A corpus-based EAP course

for NNS doctoral students: Moving from available specialized corpora to

self-compiled corpora. English for Specific Purposes,

25(1), 56–75.

Eric Friginal is professor of applied linguistics

at the Department of Applied Linguistics and ESL and director of

International Programs at the College of Arts and Sciences, Georgia

State University.

Peter Dye is an

English instructor and academic manager in Oglethorpe University’s

International Study Center. He has taught a range of EAP/ESP courses in

Spain, South Korea, and the United States.

Matthew Nolen is an English language instructor and the Language

Program director at Conexion Training, Panama. His research interests

include corpus linguistics in the classroom, data-driven learning, and

learner autonomy. |