INTRODUCTION

This past year I have been working with a first-grade bilingual teacher in an elementary school in a small rural community in the northwest United

States. The class has 22 children, 15 boys and 7 girls. All of the children in this classroom are of Latino backgrounds, and they speak either mostly

Spanish or both Spanish and English at home. The class is part of a transitional bilingual program, in which instruction in all subjects is delivered

in Spanish, with the exception of a daily 30-minute block for English language development. Typical of most transitional bilingual programs in the

United States, the percentage of class time taught in English increases as students go through the elementary grades. By fifth grade, 50% of the

instructional time is delivered in Spanish and the other 50% in English. It is significant that this school promotes both Spanish and English literacy

up to fifth grade, as opposed to transitioning into monolingual English instruction after the second or third grades, as is common in many early-exit

transitional programs. Unfortunately, the district doesn't support bilingual programs at the middle or high school levels, so instruction is delivered

solely in English starting in sixth grade. Therefore, despite a strong bilingual program at this elementary school, it could be argued that the

district's policy toward bilingual education is subtractive in nature. Bilingual education is being used as a vehicle to promote English language

development for language minority students.

In collaborating with this first-grade teacher, I have been impressed by the progress that the students made in 1 year, in terms of both literacy

skills and engagement in academic content. As I reflect on the practices I have observed in this classroom, three salient themes come to mind, which I

think represent the foundation for these students' academic achievement: (a) participation in rich literacy experiences; (b) engagement with

challenging academic content; and (c) collaboration with families. In this article I expand on each of these three themes by describing specific

classroom practices that have contributed to these students' success. I share descriptions from this particular classroom so others may be inspired to

formulate similar approaches for their own teaching contexts.

PARTICIPATION IN RICH LITERACY EXPERIENCES

Students in this classroom participate in a variety of activities that help them to become effective readers and to enjoy reading. These students first

learn to read in their primary language, Spanish. As Cummins (2001a) pointed out, learning to read in one's first language is one of the most

significant factors for success in reading in the second language. In addition, the school library has an impressive collection of both fiction and

nonfiction bilingual books that reflect culturally relevant themes with which the children can connect. The teachers make extensive use of these

library resources―they use the books in their classrooms and also encourage the children to check them out for home use.

The literacy tasks performed by this class reflect an interactive approach that includes both top-down and bottom-up processes. Bottom-up activities

help these first graders learn skills such as reading and writing from left to right, decoding sound-symbol relationships, and recognizing

high-frequency words on a page. These bottom-up activities in this classroom are done in context, so they foster top-down processes as well. An example

of an activity the class does on a daily basis is to work on nursery rhymes and chants and recognize beginning and ending sounds and also to identify

sight words (i.e., common words that do not follow a decoding rule or pattern).

The class also works on multiple top-down activities that are meaning-centered, in which students are encouraged to connect the content of what they

read with their background knowledge and experiences. The class engages in rich conversations about the texts, promoting students' comprehension and

deepening their connections with the stories or the characters. For example, after a period of extended free reading time, the teacher gathers with the

students on the carpet and asks each of them questions about what they have just read. The questions may require the students to summarize main ideas,

to make predictions of what will come next, to connect the theme of the reading to a personal experience, or to try to figure out the author's intent

in writing the particular text. Many times, the whole class engages in in-depth discussions about a particular story, with the teacher asking guiding

questions to help the students further their understandings.

One technique used by this teacher is the CAFE system (Boushey & Moser, 2009), which is an approach that focuses on a variety of literacy

strategies to help students develop skills in four areas: comprehension, accuracy, fluency, and expanding vocabulary (hence the acronym, CAFE). It gives the teacher a coherent framework for training students to read independently

and for conducting ongoing assessments to keep track of individual student's strengths and weaknesses. After modeling a particular reading strategy

through whole-group instruction (e.g., "predict what will happen and use the text to confirm") and having the students practice using the strategy with

partners, the teacher encourages the students to practice it during daily independent reading times. A CAFE "menu board" is posted on the wall (see

Figure 1) to help the children remember the strategies they have learned and to connect new strategies to the ones already on the menu.

ENGAGEMENT WITH CHALLENGING ACADEMIC CONTENT

Schleppegrell (2009) reminds us that academic language is significantly different from everyday language, and that teaching academic registers means

much more than simply teaching new vocabulary. Students must be engaged in the specialized ways of making meaning reflected in the different academic

genres. Cummins (2006) proposed an "academic expertise framework," which emphasizes "critical literacy, active learning, deep understanding, and

building on students' prior knowledge" (p. 57).

The teacher in this classroom engages in instructional conversations with the students that reflect the ways of thinking and meaning-making of the

particular disciplines. Her goal is always to get students to develop deep knowledge of the content being studied, as opposed to simply memorizing

isolated facts. Through these conversations she is also able to relate formal, school knowledge to the student's individual, family, and community

knowledge. One way she accomplishes this is through the use of a pictorial input chart (Brechtel, 1992), which involves drawing a picture while at the

same time describing important vocabulary and concepts through a mini-lecture and dialogue. During a unit on the water cycle, for example, the teacher

described concepts such as evaporation, condensation, precipitation, and accumulation while conversing with the children and drawing a picture on large

butcher paper (see Figure 2).

Both the picture and the conversational format of the lecture allowed the children to make connections between concrete and theoretical (abstract)

knowledge and to learn how to use high-level academic vocabulary in context. On subsequent days, the teacher used the chart for review of concepts and

vocabulary. She pointed to different parts of the chart and asked comprehension questions. Information was continuously added to the picture as the

students expressed their own understandings. Later, the students were able to summarize main ideas and recall details by producing their own individual

pictorial input charts. The students were engaging with key ideas of the discipline of science in the same way that scientists do. They were using the

same patterns of thinking and reasoning that experts use (Gibbons, 2009).

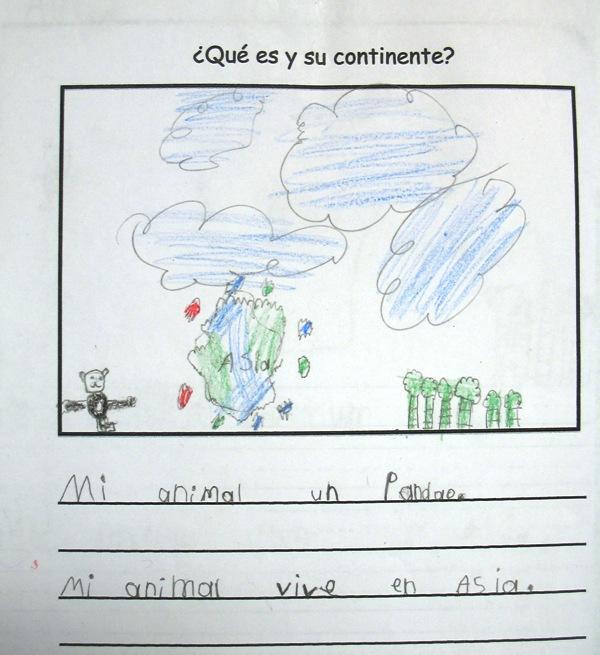

Several of the tasks in this classroom also require the students to transform information and use the content they have learned for a different

purpose. For example, after studying about animals and habitats, the students created and published "an animal book" (see Figure 3). Every student was

provided with the same table of contents. On each page of the book the student was to answer a specific question about his or her chosen animal:

"¿Cual es su continente?," "¿Dónde viven?," " ¿ Qué comen?," "¿Quiénes son sus enemigos?" On the last page, "Sobre

yo," the students were encouraged to add extra information about their animal and about themselves. On each page, the students drew a picture

representing the information on the page and wrote one or two sentences answering the question. As Gibbons (2009) pointed out, this type of task

involves "reconstructing knowledge for new contexts, different purposes, and/or other audiences or into another medium or artifact, [which translates

into] considerable amounts of learning" (p. 22).

COLLABORATION WITH FAMILIES

This first-grade teacher understands the value of creating collaborative partnerships with parents and families. These partnerships not only help

parents understand schooling practices so they can support their children's academic work at home, but they also help teachers learn about resources

and cultural practices from the homes and communities so they can use them to teach academic skills (González et al., 2005). This teacher strives

to create a school environment in which parents are welcome and feel that their input is valued. To this end, she organizes several events that bring

the students' families into the school and acquaints parents with the classroom activities their children are experiencing. One type of event is a

"family literacy night," where parents are introduced to literacy techniques such as reading aloud, paired reading, and shared writing that can be

replicated at home (Gabriel & Mize, 2010). Other events involve cultural celebrations. For example, the school recently held a celebration for

"día de los niños," with several activities for the children and their families, such as arts and crafts, games, and dances. Through these

events, this teacher establishes trusting relationships between the families and the school that will benefit the children throughout their academic

careers.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

This teacher is fortunate to work with supportive administrators and colleagues and to have access to valuable resources such as an excellent school

library and helpful professional development opportunities. A cohesive school environment reinforces and extends the practices she implements within

her classroom. She is also aware of her limitations, so she doesn't hesitate to ask for help. Recently, for example, she consulted with the district's

bilingual literacy coach, who advised her on issues related to assessment.

Cummins (2001b) pointed out that teachers have choices regarding the role definitions they adopt vis-à-vis culturally and linguistically diverse

students and their families. These role definitions are enacted through their attitudes toward the language and culture of their students, through

their interaction with parents and the community, and through the practices they use for instruction and assessment in the classroom. He added that

"the role definitions of educators can be described in a continuum, with one end promoting the empowerment of students and the other contributing to

the disabling of students" (p. 660). Clearly, this teacher has a reflective role definition as an educator. She uses the support structures already in

place at her school and builds on them to foster student empowerment. Her desire to expand her own learning and to serve her students and their

families will allow her to continue to seek ways to advocate for her students and create challenging and engaging tasks for her classroom that promote

biliteracy and academic success.

REFERENCES

Boushey, G., & Moser, J. (2009). The CAFE book. Engaging all students in daily literacy assessment and instruction. Portland, ME:

Stenhouse.

Brechtel, M. (1992). Bringing the whole together: An integrated, whole language approach for the multilingual classroom. San Diego, CA:

Dominie Press.

Cummins, J. (2001a). Negotiating identities: Education for empowerment in a diverse society (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: California Association for

Bilingual Education.

Cummins, J. (2001b). HER Classic: Empowering minority students: A framework for intervention. Harvard Educational Review, 71(4), 649-675.

Cummins, J. (2006). Identity texts: The imaginative construction of self through multiliteracies pedagogy. In O. García, T. Skutnabb-Kangas, &

M. Torres-Guzman (Eds.), Imagining multilingual schools: Languages in education and glocalization (pp. 51-90). Clevedon, England: Multilingual

Matters.

Gabriel, S., & Mize, K. (2010). Bilingual family literacy nights: A first-grade story. In M. Dantas-Whitney & S. Rilling (Eds.), Authenticity in the language classroom and beyond: Children and adolescent learners (pp. 209-227). Alexandria, VA: TESOL.

Gibbons, P. (2009). English learners, academic literacy, and thinking. Portsmouth, NH: Heineman.

González, N., Moll, L., Floyd-Tenery, M., Rivera, A., Rendón, P., Gonzales, R., et al. (2005). Funds of knowledge for teaching in Latino

households. In N. González, L. Moll, & C. Amanti (Eds.), Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practice in households, communities and classrooms (pp. 89-111). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Schleppegrell, M. J. (2009). Language in academic subject areas and classroom instruction: What is academic language and how can we teach it?

Retrieved July 13, 2010, from www7.nationalacademies.org/cfe/Paper_Mary_Schleppegrell.pdf

Maria Dantas-Whitney, Western Oregon University, mdantasm@wou.edu