|

The Project: The Three-Step Short Story The Project: The Three-Step Short Story

I have found that no form of writing does as much for ELLs as does creative writing. One extremely effective activity within the vast network of creative writing genres is the three-step short story. Through this project, students develop an understanding of strong versus weak lexical items, examine the use and power of various sentence types, learn how to create the characters of a story, produce realistic dialog, and evoke emotional responses from the reader.

The completed project is a two and a half to three page short story based on the meaning and feelings behind the word “Saturday.” These stories contain all the basic literary elements of a short story: setting, character, plot, conflict, and theme.

The Procedure

DAY ONE: From Poetry to Prose—The Significance of Words

I always start this project with a poem. This gets the students to feel, think, and discuss the sensory qualities and representations of words. Let us use “Finger Kiss” as an example.

Finger Kiss

What color

Do our fingers see

When they close

Their eyes and kiss—

Swinging between

You and me

On this Saturday

In the park?

(Randolph, 2011, p.79)

After reading the poem, students pair up and discuss its meaning and answer the question that the poem poses. After this pair work, I open it up for a lively class discussion. Then, we examine the sensory qualities of the words. For example, “What is the sense that fingers experience?”; “Can fingers see, smell, or taste?”; “What image does ‘swinging’ elicit?”; “Describe some sounds of a park.” Next, we talk about the significance of Saturday in the poem, and this takes us down the path of rediscovering all the wonders and magic of Saturday. We consequently examine what really makes Saturday the best day of the week.

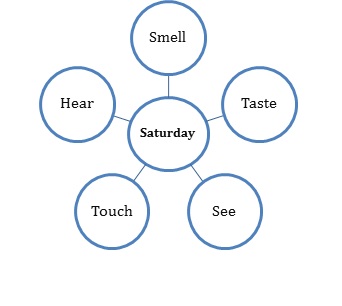

This is followed by a brainstorm session in which we look at all the senses and their relation to Saturday. The diagram shown in Figure 1 is used to elicit their responses.

Figure 1. The Sensory Play With Words

To get the students thinking more about this, I ask them such questions as “What color comes to mind when I say Saturday?”; “What sounds do you associate with Saturday?”; “Whose face comes to mind when I mention Saturday?”; “What is your favorite memory of Saturday?”

The homework for the next day is to write a descriptive paragraph on the following prompt: “Why is Saturday important to you? Describe why this day is so significant and explain what you like to do on this fantastic day of the week.”

DAY TWO: The Three-Paragraph Story

On the second day, check over your students’ paragraphs. You will likely find that they have given you an impressive list of all the things they do. What we do next is to turn one of those points into a three-paragraph short story.

After checking over the paragraphs, start a discussion on the elements of a short story. You can have the students choose a favorite movie or TV series and explain why it is interesting and why they enjoy it. During this discussion, elicit the elements of a short story: characters, setting, plot, climax, and theme. For the purpose of our activity, you can simplify the plot as (1) the set up, (2) the problem, and (3) the resolution.

The homework for the next day is to create a three-paragraph short story based on one of the points they wrote about the day before: the first paragraph is a set up of the situation, which includes the main character and the setting; the second paragraph describes a problem; and the third paragraph offers a resolution.

For example, one student recently discussed all the things that he and his wife like to do on Saturdays. However, he also mentioned that due to his busy school schedule, he even studies on Saturday nights. So this became the basis for his short story: paragraph one set up the image of a happy international student enjoying the early evening with his wife; paragraph two introduced the conflict of not having enough time to share with her; paragraph three showed how he would work harder during the week so that he could be with the person he treasures most on that special evening of the week.

DAY THREE: Making It All Come Alive

This lesson focuses on adding a second character and dialog to their stories. If they already have a second character, as was the case in the above example, then there is no need to add another.

In the first part of this lesson, you can work with the students on their stories by teaching useful adjectives and creative metaphors; for example, “She had crescent-moon shaped eyebrows” or “Her laughter was as soft as an April morning sun.”

A fun and effective activity is to have each student pair up with a classmate and write a “physical character sketch” by describing their partner as precisely as they can. The instructor can then read these to the class and have the students match their classmates with the character sketches by listening to the descriptions.

The second part of this lesson should be devoted to adding dialog to the stories. You will need to go over the basic format and punctuation style of dialog. It is also wise to discuss the variation of verbs that can be used in dialog instead of just having the students use the “he said, she said” formula. For instance, instead of “’Oh no!’ she said,” you could use “’Oh, no!’ she cried,” or “Oh, really,’ she whispered softly.” This will help the students see the importance of assigning particular verbs to particular statements to reflect the emotion or connotation of the utterance. The homework, then, is to complete the first draft of their stories by adding a character and dialog.

DAY FOUR: Four Eyes Are Better Than Two

On the fourth day, the students pair up and read their stories to each other. Here, they are asked to peer edit/critique their stories. It should be noted that this activity is most effective if both partners simultaneously critique one story at a time. If students read each other’s at the same time, the peer edit/critique session does not work, for it becomes an isolated activity.

It should also be noted that this session can easily turn into a grammar editing session, so monitor the pairs as closely as possible to make sure they are critiquing the content and the elements of the short story. It is best to provide them with a rubric for the activity (for a ready-made rubric, please email the author) and go over it before starting. The homework for day four is to have them work on the final touches of their first draft.

DAY FIVE: The Stories Revealed to the Class

The project culminates with the instructor reading sections of the stories aloud to the class. This is best done after the instructor has had time to go over each story and highlight the sections that he or she feels the class would benefit from the most. I like to read the students’ work to the class for two critical reasons: first, it inspires the students and instantiates the idea that their stories are something to be taken seriously; and second, it creates a sincere sense of mutual admiration among the writers (Koch, 1978).

Depending on the time you want to take on this project, you can do a second or even third draft of the stories. These rewrites can be done as in-class activities or assigned as homework. From personal experience, I would say that a minimum of two drafts is necessary, and three, if you are thinking about submitting them to an ESL writers’ journal.

Concluding Remarks

I do not claim that creative writing will magically solve all the problems that students encounter in their writing process, but I will argue that it is a fun, effective, and helpful way to get them more involved with the dynamics of writing. It will foster a positive way in which they can gain more control over their writing skills and develop confidence in both their writing and in themselves as writers.

References

Koch, K. (1978). I never told anybody: Teaching poetry writing in a nursing home. New York: Vintage Books.

Randolph, P. T. (2011). Father’s Philosophy. Delevan, WI: Popcorn Press.

______________________________

Patrick T. Randolph specializes in creative and academic writing, speech and debate. He continues to research current topics in neuroscience, especially studies related to exercise and learning, memory and mirror neurons. He lives with his wife, Gamze; daughter, Aylene; and cat, Gable, in Kalamazoo, MI. Randolph has published two best-selling volumes of poetry; Father’s Philosophy and Empty Shoes – Poems on the Hungry and the Homeless. All proceeds from the latter go to benefit Feeding America.

NOTE: A version of this article first appeared in the IEPIS Newsletter (September 2013). Used with permission. |