|

Humor is an area often overlooked in the language classroom.

This fact is reinforced by curricula that don’t include it, and we assume that

our students serendipitously pick it up on their own. In reality, humor is

important for our students, especially those in an English as a second language

(ESL) setting.

Humor is an area often overlooked in the language classroom.

This fact is reinforced by curricula that don’t include it, and we assume that

our students serendipitously pick it up on their own. In reality, humor is

important for our students, especially those in an English as a second language

(ESL) setting.

In American

culture, we use humor all the time. Humor accomplishes speech acts, establishes

ingroup boundaries, influences others, and builds rapport, among other things.

It tells the learner what the culture values, and what its members pay

attention to. Additionally, ESL students want to understand and engage in humor

to feel they belong in a new culture. Making an error in humor could be damaging

to this endeavor. After all, sociolinguistic errors are riskier than formal

linguistic ones. This was my experience living internationally, as well. I felt

like the picture in Figure 1.

Because

humor is so important, my colleagues, Haeyuk (Nicole) Jeong, Dr. Cheri Pierson,

and I decided to use Bell’s (2011) excellent summary of humor research and

apply it to our adult ESL classroom. In this article, I will first define

humor, then provide the steps we took and a few suggestions for your own

classroom to become a little funnier.

Figure 1. Missing the joke.

(From http://www.pinterest.com/pin/290693350948535396/)

What Is

Humor?

To apply

humor research to the classroom, we first needed to understand what humor is.

According to the General Theory of Verbal Humor, we create humor by juxtaposing

scripts, or the expected direction and characteristics of a conversation (Bell,

2011). We accomplish this by changing topic, meaning, word choice,

pronunciation, morphology, syntax, and the like. When we do this, we often

provide cues to our co-communicator that we are veering off course. These cues

could be changes in our facial expression, intonation, register, formality, or

word choice. (One reason irony is complicated for language learners is because

it is characterized by an absence of cues, making it much more difficult to

detect [Attardo, 2000].) Our guess was that if our ESL students could learn to

correctly sense the cues of a changed script, they could then learn to

participate more fully in native speaker humor, thus feeling more a part of the

English-speaking community.

How Do We

Teach It?

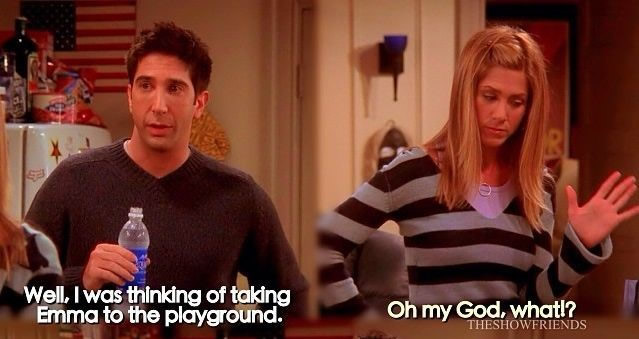

We all know that

humor isn’t funny if we have to explain it, so in our approach, we sought to

provide our students with a few humor principles, then gather their thoughts on

a Friends clip. In the clip, Ross offers to take Emma to the playground, and

Rachel reacts out of the memory of her own precarious encounter with a swing

set (Crane et al., 1994; see Figure 2). Many of our students had children, so

this would be relatable content. (See the clip at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UxzcKY7D42I.)

Figure 2. Meme from Friends clip. (From http://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/169729479682015036/)

My

colleagues and I stuck with two main humor principles and formed them into

objectives for this intermediate lesson. First, we wanted our students to

demonstrate a raised awareness of humor cues from the clip. Second, we hoped

our students would be able to recognize that humor breaks the rules. Following,

I’ve listed several steps you can take in creating a humor lesson, along with

our own story for clarification.

Teaching the

Nuts and Bolts of Humor

-

First,

choose the appropriate text or clip. This is an art form. The content of the

clip must be comprehensible for your students, even if the humor might not be. We provided our students with a script for their own marking and to help with any confusing or fast speech. Generally, clips with exaggerated body language or intonation are helpful in the beginning, as these are easier to detect than small changes in word choice or syntax.

-

Activate students’ schema of previous sociolinguistic lessons and their own culture’s humor. Prior to our humor lessons, we completed several lessons on small talk in the United States, from appropriate demeanor to common topics. In our first humor lesson, we asked students what they find funny in their own culture, as students have a myriad of examples from their own lives. We then built on our small talk foundation by discussing American culture’s appreciation of humor in small talk. Many students indicated that this differs from their own cultures. We thought this would be the most important aspect of humor to tackle, as students would not likely engage in humor if they viewed it negatively.

-

Show how humor breaks one rule. In our class, we started by showing that humor breaks the rule of topic (See Chart 1 in the worksheet, Appendix A [.docx]). Our students provided the small talk topics as review, and we gave them the humor topics. We were careful to encourage students not to immediately go out and make jokes about these several taboo topics. We emphasized that, if humor broke topic rules, it might also break others, and they should try others first. The reason we started with topic as a rule is that students would be familiar with jokes in these topics in their own languages, as Driessen (2004) states.

The topics we included for juxtaposition were: sex/gender, age, language, politics, religion, and ethnicity. These are noticeably different from mundane small talk topics of weather, jobs, sports, entertainment, appearance (compliments), and family/relationships. We encouraged them, if they wanted to try a joke in this area, to stick with jokes about themselves in their own culture. Self-deprecating humor is always a safer bet than jokes about others.

-

Introduce the other rules that will appear in the clip or text. In the worksheet key (Appendix B [.docx]), you’ll see that we included four rules that humor breaks: topic, expectation, intonation/pronunciation/stress, and body language. The second rule, expectation, was our attempt to communicate with our students that humor breaks the rules of word choice. We used examples of jokes our students had made before. One included a discussion of whether rent cost US$200 per month, during which a student, instead of answering “true” or “false,” answered, “Yeah, I can only rent a door for $200 per month.” She broke the script of an academic response, choosing to give a different answer, using unexpected words. We then covered the rules of pronunciation and body language, as we’d already talked about these in relation to other topics, giving silly examples from the front.

-

Watch the clip as many times as you have rules. We watched the clip first for a preview, asking general comprehension questions: Who are the characters? What are they talking about? Where does Ross want to take the baby? Next, we watched it once per rule, four times, so students only had to search for one rule per viewing.

They wrote their examples from the video in the chart at the bottom of their

worksheet, and we discussed them after each rule. This went well, overall, as

students found examples we hadn’t thought of.

Tips on

Incorporating Humor Pedagogy Into Lessons

Maybe you

don’t feel like taking two entire lessons to teach humor. That makes sense!

Here are some tips on how you can incorporate humor research and pedagogy into

existing lessons or conversations. Remember, the goal is not to create comedy

specials, but to raise learners’ awareness of humor cues, so they can navigate

humor in their new language. Maybe you

don’t feel like taking two entire lessons to teach humor. That makes sense!

Here are some tips on how you can incorporate humor research and pedagogy into

existing lessons or conversations. Remember, the goal is not to create comedy

specials, but to raise learners’ awareness of humor cues, so they can navigate

humor in their new language.

-

Capture

humor in class. Start by capturing moments of naturally occurring humor in your

class. Write them down, assess which rules they break, and revisit them when appropriate. This removes the pressure we can feel to be funny, and seeks to raise awareness of what’s already occurring. The affirmation you give is important for learners’ confidence. Online learning often provides for even more hilarious scenarios than in-person learning, so you’ll probably have a lot to work with.

-

Make it a cultural discussion. If you have conversation practice, don’t be afraid to approach the topic of humor, asking students who and what they think is funny, or when the last time was that they had a good laugh. They could discuss this in breakout rooms with others who speak their first language, so they can better explain it to the rest of the class in English. This provides students with agency to lead the conversation on humor. You can also provide information about the culture in which you teach (especially in an ESL context).

-

Start with other, more rule-focused pragmatics lessons. These could be things like giving compliments, expressing gratitude, or taking leave, which are more likely to be in your curriculum. You can provide students with “normal” ways to accomplish these, then one appropriate, funny way according to your cultural context. For example, if I have some students who want to be funny, we can brainstorm silly excuses for needing to leave from a hangout with friends. If they’ve spent a long time there, maybe they could say, “Okay, well I have important things to do like reorganizing my sock drawer, so I’ll see you later.” The fact that they’ve spent a long time with their friend before this helps the friend not take offense. Proper intonation and facial expressions are important for our students to know, as well. This approach can help you introduce rule-breaking while reducing the risk for them.

-

Choose clips your students recognize. Collect suggestions of what your students are already watching in English to choose clips they might like. We used Friends as a baseline because many had seen some of it before.

-

Go slowly. Start with one rule at a time and discuss that rule several times

before introducing other rules. This way you can incorporate humor pedagogy bit

by bit.

Conclusion

Because of

extensive preparation, scaffolding, and schema activation, our learners were

prepared to analyze a clip according to the rules we’d discussed. Many found

the clip funny, or were at least able to follow the laugh track. In hindsight,

we would recommend doing this lesson in a college ESL setting like an intensive

English program, where students have ample interaction with native speakers

outside of class.

In the end,

we encouraged our students to find funny things around them and bring examples

to class. At the very least, we could have a positive atmosphere, enjoy each

other’s company, and increase their sense of agency in participating in

American culture. I hope that if you take some of these tips or suggestions to

heart, you find that you have a deeper connection with your class and enjoy

English language teaching that much more.

References

Attardo, S.

(2000). Irony markers and functions: Towards a goal-oriented theory of irony

and its processing. RASK: Internationalt Tidsskrift for Sprog Og Kommunikation,

12, 3–20.

Bell, N.

(2011). Humor scholarship and TESOL: Applying findings and establishing a

research agenda. TESOL Quarterly, 45(1), 134–159.

Crane, D.

(Writer), Kauffman, M. (Writer), & Bright, K. S. (Director). (1994).

The one where Rachel finds out [Television series episode]. In K. S. Bright, M.

Kauffman, & D. Crane (Producers), Friends. Burbank, CA: Warner Bros.

Studios.

Driessen, H. (2004). Jokes and

joking. In N. J. B. Smeler & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), International

encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences, 7992–7995.

Elsevier.

Anna O’Neal

is an ESL instructor in Chicago, Illinois, USA. She lived internationally for 5

years, providing useful and painful fodder for her research in humor. She has

taught adult ESL at World Relief and in the Intensive English Program at the

University of Illinois at Chicago. She and her colleagues presented their work

on humor pedagogy at the 2019 Illinois TESOL conference, and will present

online for the TESOL International Association 2021 Virtual

Convention.

|