|

Hybrid, hyflex, flipped, face-to-face, remote learning…we

are now faced with so many instructional modalities. What they all have in

common is a mix of synchronous and asynchronous learning—in other words, some

real time and some independent online time.

Hybrid, hyflex, flipped, face-to-face, remote learning…we

are now faced with so many instructional modalities. What they all have in

common is a mix of synchronous and asynchronous learning—in other words, some

real time and some independent online time.

In a sense,

this is not new because, traditionally, students have always had a mix of classwork

and homework. If we use this as our starting point of common understanding, we

can easily move into blended learning—a mix of instructional modalities.

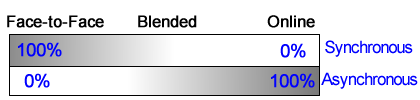

Blended learning can now be thought of as either a mixture of face-to-face with

online (traditional definition) or a mixture of real-time video chat (e.g.,

Zoom, Google Meet, or Teams) with online (more common now as a result of the

COVID-19 pandemic). Either way, blended learning can be optimized through

intentional planning of the instruction in the two modalities—synchronous and

asynchronous (McGee & Reis, 2012). See Figure 1 for a breakdown of

instructional modalities, from fully face-to-face to fully online.

Our

interpretation of blended learning is a

seamless integration in that both modalities are always working to support each

other. What students are doing independently online supports and

aligns with what is happening in the real-time classroom. The interactions of

learner-learner, learner-content, and learner-teacher seamlessly exist in both

modalities. Look at the vocabulary lesson presented in Appendix A to see how

content can be delivered differently and similarly in multiple

modalities.

|

In a fully synchronous classroom, students and instructors communicate and collaborate only through face-to-face interactions. Instruction does not use telephonic, postal, or other courier services to facilitate peer‑to‑peer or student‑instructor communication and collaboration. |

A blended classroom may include few or many ways for peer‑to‑peer and student‑instructor communication to occur. Classroom meetings may be solely face-to-face, or they may use remote learning techniques for some or all the students. Peer‑to‑peer student‑instructor communication and collaboration may occur in multiple ways, such as by sharing the same physical space, by post, or by using instant messaging apps on smartphones. Each decision regarding the use of remote education techniques is independent of other decisions and is made to increase student success. |

In a fully asynchronous classroom, all communication between students and instructors occurs remotely. This may include the use of computers and tablets, telephonic equipment, or the use of the postal service. |

Figure 1.

Course modalities.

In 2020,

because of the COVID-19 pandemic, blended learning came to the forefront as we

quickly shifted to online learning, but many times still maintained a

synchronous presence via video. Blended learning provided learners and teachers

with an array of opportunities. Learners reached greater possibilities of

independent learning while still having the support of the instructor through

real-time video chats. This was many times a difficult and challenging process

as educators were pushed into new and sometimes uncomfortable realms. We

learned new technologies and techniques to create an engaging blended

environment.

Course Design and Delivery in Blended Learning

Traditionally, blended learning

allows for more flexibility in terms of time and collaboration and has been

understood as course delivery—in other words, how we deliver and teach a

course. But it should also be thought of as course design—in other words, how

we imagine and build the course from the beginning. Shifting the focus to

course design first to determine the right blend of time can make delivery more

intentional. Intentional course design is a key focus in a flexible blended

format.

Hybrid and

flipped learning are commonly delivered at time ratios of 50/50 for in-class

and out-of-class work. However, that may not be the optimal blend of time for

all students, contexts, and courses. The right blend of time involves

intentional design and alignment of course elements, technologies, and

interactions between learners, teacher, and materials. One way to look at this

is by determining whether content and activities need to take place online

asynchronously or in the synchronous environment (Chatfield, 2010).

We can

examine it in more detail by looking at what needs to occur before the

synchronous meeting, during the synchronous meeting, and after the synchronous

meeting. For example, readings and videos might be assigned prior to class to

get students activating their background knowledge. Then, in-class activities

could focus on discussions and collaborations. Follow-up online activities

could be self-assessments, summaries, and synthesizing information.

Alternatively, a context might require that students need more teacher

explanation and feedback in the synchronous time, and discussions and

collaborations occur in the asynchronous environment. We can

examine it in more detail by looking at what needs to occur before the

synchronous meeting, during the synchronous meeting, and after the synchronous

meeting. For example, readings and videos might be assigned prior to class to

get students activating their background knowledge. Then, in-class activities

could focus on discussions and collaborations. Follow-up online activities

could be self-assessments, summaries, and synthesizing information.

Alternatively, a context might require that students need more teacher

explanation and feedback in the synchronous time, and discussions and

collaborations occur in the asynchronous environment.

When and

where content occurs will be specific to the class, the modality, the level of

the students, and the expectations of interactions. Lower level students or

students early in a course may need more content presented in class initially

with more online work as a follow-up to the in-class presentation and

activities. Later, students may become more independent within the course and

be able manage self-directed learning by taking on more responsibility for the

coursework up front. Then, class time can focus on group work, hands-on

projects, and student teaching.

Be creative!

Teaching can take place in class or online, depending on the nature of the

task. The content should be intentionally designed to occur synchronously or

asynchronously.

Planning for Blended Learning: The Right Blend of Time

So how do

you decide? How do you plan? To begin, we recommend mapping out course elements

and design while also allowing for built-in flexibility. The map will be your

guide and allow you to build lesson plans and the course itself. This results

in the right blend of time, which is the ratio of in-class/online or

synchronous/asynchronous work. For some classes, it still may be a 50/50 ratio;

other classes could result in more time spent in class, such as 60% in class

and 40% online (or 60/40), while others may result in less in-seat time, such

as 40% in class and 60% online (or 40/60).

For example,

let’s consider a lower intermediate course at a community college where many

students come from countries without technology access. Based on these factors,

a blended course that allows for about 70% face-to-face instruction will allow

the students to engage in more listening and speaking interactions while also

developing independence and confidence in online, independent work. In

contrast, suppose you have a course of international scholars with advanced

degrees from their home countries; these students are self-regulating and

highly motivated learners, so a blended course of 70% independent work may

allow for these learners to focus on interactive discussions during the shorter

face-to-face sessions.

With large

classes (100+ students), you may consider creating smaller groups that meet

together for face-to-face discussion of materials once a week; in this case,

the ratio may be close to 80% online and 20% in class. Table 1 lists many

different factors to consider for your own unique student groups and teaching

contexts.

Table 1.

Factors to Consider for the Right Blend of Time

|

Course Context |

Students’

Context |

|

Institution/program mandates on online

learning |

Language level |

|

Time allotment

for the course |

Experience with

technology and the technology available to them |

|

Learning

Modality

online asynchronous, video conferencing,

face-to-face without social distancing, face-to-face with social distancing,

room size for face-to-face |

Ability to

self-regulate learning |

|

Size of the

class |

Age |

|

Delivery Style

lecture,

conversation, collaboration |

Educational

level |

|

Types of

materials available (online, hard copies) |

|

You may not

find the exact right blend of time at first. Reflect on what’s working, what

needs to be improved, and how your learners seem to be responding (you may even

consider polling students or collecting their feedback through short formative

assessments); be open to making changes if needed.

The course

alignment map in Appendix B shows you how a reading course is mapped out for

alignment and includes three scenarios for how the right blend of time is

determined.

Now it’s

time for you to map out your own course elements and plan for the right blend

of time for your context. (See Appendix C for a blank course alignment map;

.docx)

Conclusion

The COVID-19

pandemic forced educators and students to reassess the modality of learning

when peer-to-peer and peer-to-faculty interactions became impossible; however,

by the beginning of this century, the blending of remote and face-to-face

communication and collaboration had already become common in the classroom. The

primary issue remains the necessity of using a particular modality to meet a

specific pedagogical objective.

Faculty

should design courses with the needs of the students and the reliability and

availability of asynchronous learning modalities in mind. By mapping the course

elements, lesson plans can integrate synchronous and asynchronous learning

methods to ensure the optimal blend of time for each context.

References

Chatfield,

K. (2010). Content “loading’ in hybrid/ blended learning. Sloan-C Effective

Practice. http://sloanconsortium.org/effective_practices/content-quotloadingquot-hybridblended-learning

McGee, P.,

& Reis, A. (2012). Blended course design: A synthesis of best

practices. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks,

16(4), 7–22. http://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v16i4.239

Sarah

Barnhardt is an associate professor of ESOL

and an online learning coordinator at the Community College of Baltimore

County. She has a keen interest in online learning for English learners and has

done research in course design and alignment for online learning. She enjoys

creating and teaching ESOL courses that truly engage and motivate students for

any modality. She is also a coauthor of the Learning

Strategies Handbook.

Jessica

Farrar is an ESOL instructor at the

Community College of Baltimore County. She has taught blended, fully online,

and synchronous courses in a variety of contexts, from classes with just five

students to those with more than 300. She enjoys developing integrated skills

curricula, engaging students in authentic writing tasks, and collaborating with

colleagues.

Chester

Gates is an adjunct professor of ESOL at

the Community College of Baltimore County. He has taught ESOL for more than 20

years using both synchronous and asynchronous methods. He has also been an

instructor in the Academic Literacy program and is a trained instructor in the

Accelerated Learning Program. He is an active stepfather to an adult with a

cognitive disability, a returned Peace Corps volunteer (Congo, 1990), and a

birdwatching enthusiast. |