|

From the spring of 2020 until the summer of 2021, all of my

English classes were online. Even as I grew accustomed to this (for me)

completely new teaching format, I also realized an integral part of the

classroom experience was sorely missing: the sound of my students’ laughter. I

thus found myself sadly nodding my head (and I know I wasn’t alone) when

reading an

article by Henderson (2021) in which he discussed the negative impact

of online teaching on humor use. He argued that humor is more difficult to

incorporate in the online format because of, among other reasons, From the spring of 2020 until the summer of 2021, all of my

English classes were online. Even as I grew accustomed to this (for me)

completely new teaching format, I also realized an integral part of the

classroom experience was sorely missing: the sound of my students’ laughter. I

thus found myself sadly nodding my head (and I know I wasn’t alone) when

reading an

article by Henderson (2021) in which he discussed the negative impact

of online teaching on humor use. He argued that humor is more difficult to

incorporate in the online format because of, among other reasons,

- missed context cues,

- poor audio or video connections, and

- less contagious laughter.

In the classroom, humor is a powerful tool that

teachers can turn to in order to lighten the atmosphere, make speaking in the

target language less intimidating, and enhance the teaching of grammar or

vocabulary. Though the spontaneous joking that helps to improve the atmosphere

of traditional language classes is indeed much more challenging when you are

speaking into your computer and looking at video thumbnails (of webcams which

may or may not be on), it is not all bad news. Humor merely needs to be

modified, not eliminated, when it comes to online teaching. Additionally, there

are some advantages to the online format. The online teaching format can

provide

- a safe environment for experimenting with

humor,

- more time for learners to digest the humor,

and

- the opportunity to focus on the importance of how

humor is used online (e.g., on social media).

In the third (and final) part of this series on

humor in English language teaching (ELT), I introduce practical techniques that

illustrate these three potential advantages of humor in online teaching. (Read Part

1 on the benefits, misconceptions, and risks of using humor in ELT,

and Part

2 on classroom techniques.)

1. Online Teaching Provides a Safe Environment for

Experimenting With Humor

Pomerantz and Bell (2011) argued that “engagement

in spontaneous humorous performances can provide rich opportunities for

language use and development, beyond those habitually found in more tightly

controlled classrooms” (p. 157). Though I wholeheartedly embrace this approach,

many of my students still hesitate to engage in humorous interaction in the

classroom, either because they lack confidence or aren’t sure if the humor

lacks appropriateness.

When I assigned my students to prepare and share

prerecorded speaking videos for the class LMS in my online courses, I encouraged

them to relax and have fun. A very pleasant surprise was that students actually

incorporated humor into their speaking tasks more than in

the traditional classroom. I had a number of “this probably wouldn’t happen in

the regular classroom” moments. One of these occurred in a video presentation

in which students had to design a themed tour of Japan for international

tourists. One student chose natto (fermented soybeans

infamous for its gooey, stringy texture and strong odor; see Image 1) as the

focus of his tour. I have often advised my students that starting a

presentation with humor is a great way to get the attention of the audience.

Instead of yet another presentation starting with “My name is ____ and I will

talk about ____,” this student opened a fresh package of natto, then demonstrated the gooey texture as he stretched

the beans right up to the camera and explained the theme of his tour. He got my

attention!

Image 1. Natto.

The great thing about this student’s use of humor

is that it was contagious. Because they were mostly taking lessons from home,

other students started incorporating humorous props into their speaking videos.

As stressed in Part

1 of this series, humor should not only be teacher centered. Though

the teacher may encourage the use of humor, it is often much more effective

when it is learner initiated, as this inspires other students to include humor

in their own speaking tasks. The important thing to remember about humor,

however, is it should be used to enhance, and not replace,

learning. The natto student got an A on his assignment because

his humorous and attention-getting introduction was just one aspect of a

high-quality presentation.

Though we may lose the contagious laughter in

online teaching, classes like this one still featured a lot of (or even more!)

humor. Additionally, in self- and peer evaluations, students wrote comments

like, “Because I wasn’t in the classroom, it felt more natural to use humor”

and “Other students’ funny videos cheered me up during COVID-19.”

2. Online Teaching Gives Learners More Time to Digest the

Humor 2. Online Teaching Gives Learners More Time to Digest the

Humor

Humor can be a double-edged sword in the classroom.

Some language instructors avoid using humor because they worry that it can be

both motivating and demotivating—students who understand the humor benefit, but

students who don’t understand the humor may lose confidence and feel

frustrated. It takes a lot of time to get humor in a foreign language, and it

should be a step-by-step process in the language teaching classroom.

One way to give learners more time to digest the

humor is to create online humor “quizzes” (e.g., on Google Forms). One type of

humor that works well with this approach is satirical news. As explained in Part

2 of this series, humor instruction works best when it has value

beyond just a laugh. A deeper understanding of English satirical news helps

multilingual language learners (MLLs) to improve their

- digital literacy (e.g., understand the types of

humor that are shared on social media),

- media literacy (e.g., differentiate between real

and “fake” news), and

- understanding of English-speaking cultures (e.g.,

get insights into how humor is used to critique contemporary issues).

You can create an out-of-class online quiz that

mixes satirical news headlines with real (but offbeat) news headlines. Students

complete a Likert-style survey in which they rank each item from 1 (definitely

satirical news) to 6 (definitely real news). Sample items I have used before

include the following:

-

Namco unveils potato chip-flavored cola (real

news: Sora

News 24)

-

Teen boasts of drunken driving on Facebook,

arrested (real news: CNET)

-

Study Reveals: Babies are Stupid (satirical

news: The Onion)

-

BREAKING NEWS: Husband Cooks for Wife (satirical

news: The

Rising Wasabi)

See the full

quiz, which I created in Google Forms for my students in Japan (answer key here). Doing

this humor quiz online takes away the pressure of having trouble understanding

this form of humor. Though students may need to enter their name, student

number, or alias to get credit for the assignment, their classmates cannot see

their answers.

Whether teaching face-to-face or online, you should

provide guidance to help learners better detect and comprehend satirical news.

Simple tips that can help to differentiate satirical news items from real news

items include

- rhetorical cues (e.g., not newsworthy, absurd

situations) and

- linguistic cues (e.g., informal style, more nouns

in the title).

After providing humor construction on detecting

satirical news, I highly recommend giving a second quiz featuring new items. In

previous research I did with Caleb Prichard (Prichard & Rucynski,

2019), students were able to significantly improve their ability to detect

satirical news after just one class period devoted to humor instruction.

3. Online Teaching Provides an Opportunity to Focus on

How Humor Is Used Online

As I have stressed in this three-part series, a

deeper understanding of the humor of the target culture(s) is an integral

component of cross-cultural communicative competence. However, this includes

both humor that takes place in face-to-face communication and online

communication. Social media and other Web 2.0 platforms provide countless free

opportunities for MLLs to develop their English language skills, but the frequent

use of humor by users can impede language learners’ ability to fully comprehend

some content.

In Part

2 of this series, I explained the importance of understanding verbal

irony in intercultural communication. However, detecting and comprehending

online ironic statements (e.g., sarcastic comments on social media or other

platforms) is equally important because

- irony is frequently used on such platforms,

- cues to normally detect irony are missing (e.g.,

verbal and nonverbal cues), and

- a lack of understanding of ironic statements can

lead to embarrassment or misunderstandings.

With regards to cues for detecting irony, we have all

likely had frustrating experiences when reading an email message or Facebook

comment and not being completely sure whether the other person is serious or

joking. Decoding whether written language is ironic or sincere is even more

challenging when reading in a foreign language.

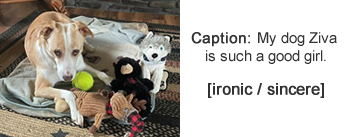

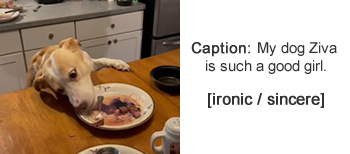

As an introduction to helping learners detect true

intent, prepare easy examples with visual support and task learners with

differentiating between ironic and sincere comments. Again, learners can do the

activities anonymously using online tools such as Google Forms or a class LMS.

You can even use the same “model” for multiple examples, such as with my

family’s dog Ziva, shown here in Images 2 and 3:

Image 2. Good Ziva.

Image 3. Naughty Ziva.

Though verbal (e.g., exaggerated intonation, flat

tone) and nonverbal (e.g., winking, rolling eyes) cues are missing in online

ironic comments, different cues are available. In another study I conducted

with Prichard (Prichard & Rucynski, 2022), we shared some tips with

learners, including the following:

|

Cue |

|

/s =

sarcasm |

|

BiG aND sMalL

lEtTeRs = sarcasm |

|

Emoji and comment

do not match ("I love rainy days... ") = sarcasm ") = sarcasm |

|

Laughing emoji  or LOL does not always mean sarcasm.

or LOL does not always mean sarcasm. |

|

Stressing a word

(CAPS). ("I TOOOTALLY love natto.") = maybe

sarcasm |

|

If a person says

something very different than you expect = maybe sarcasm |

It is important to stress that some cues only sometimes mean irony or sarcasm. For example, the laughing

emoji could follow either an ironic comment or a humorous, sincere comment.

After the simple cues (e.g., /s = sarcasm, BiG aND sMalL lEtTeRs = sarcasm),

move on to more complex tasks like identifying incongruity, or detecting

comments in a social media thread that do not seem logical. Create fictional

threads (featuring either two or multiple commenters) and task learners with

identifying whether the final comment is ironic or sincere. Here is an example:

Thread 1

A: I have to take the TOEFL test this

weekend!

B: Don’t worry. I’m sure you’ll do great!

[ironic / sincere]

Thread 2

A: I have to take the TOEFL test this

weekend!

B: That sounds like a fun weekend. I envy you!

[ironic / sincere]

As any MLL can tell you, Thread 2 features the

ironic comment!

Again, designing this type of humor quiz online not

only exposes MLLs to the types of ironic online comments they may encounter,

but also provides an anonymous format to give learners the opportunity to

practice detecting humor without potential embarrassment. Having all student

answers on a platform such as Google Forms also makes it easy for you to track

which types of humor are more challenging for your learners.

Conclusion

Although this part of the series focused on online

teaching, these three advantages are important regardless of teaching format.

Whether you are teaching face-to-face or online, it is important to provide a

safe environment for learners to experiment with humor, give learners time to

digest humor, and include a focus on how humor is used both in face-to-face

communication and online. Though Henderson (2021) was certainly correct in

arguing that using humor in online teaching does have some obstacles, I also

agree with Anderson (2011) that using humor is still a way to “take the

distance out of distance education” (p. 80).

References

Anderson, D. G. (2011). Taking the “distance” out

of distance education: A humorous approach to online learning. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 7(1),

74–81.

Henderson, S. (2021, February 5). No

joke: Using humor in class is harder when learning is remote. The

Conversation. https://theconversation.com/no-joke-using-humor-in-class-is-harder-when-learning-is-remote-153818

Pomerantz, A., & Bell, N. D. (2011). Humor

as safe house in the foreign language classroom. The modern language

journal, 95, 148–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01274.x

Prichard, C., & Rucynski Jr., J. (2019).

Second language learners’ ability to detect satirical news and the effect of

humor competency training. TESOL Journal, 10(1), e00366.https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.366

Prichard, C., & Rucynski, J.

(2022). L2 learners’ ability to recognize ironic online comments and the effect

of instruction. System, 102733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2022.102733

John

Rucynski has taught EFL/ESL in Japan,

Morocco, New Zealand, and the United States. He is currently associate

professor at Okayama University in Japan. His articles on humor in language

teaching have been published in English Teaching Forum, HUMOR, and TESOL Journal. He has also

edited New

Ways in Teaching with Humor (TESOL Press) and (with Caleb

Prichard) Bridging

the Humor Barrier: Humor Competency Training in English Language

Teaching (Rowman & Littlefield).

|