|

It is a challenge getting students to higher levels

in listening. Teachers typically assign a lot of listening practice and

answering comprehension questions in the hope and expectation that these types

of activities will help their students develop the skills needed. In this

article, we suggest a supplement to the comprehension approach, offer 11

practical strategies that focus on the process of listening, and encourage

active listening to help students develop their listening skills.

Are You Testing or Teaching Listening Skills?

How do teachers typically teach listening? From our

experience, most instructional listening activities focus on testing students’

listening comprehension rather than providing instruction to help them in word

recognition or comprehension. The teaching of listening typically has students

do some prelistening, then listen to a passage, answer content questions, fill

in the blanks with missing words/phrases, transcribe a segment of the passage,

or get the gist. All are valuable and useful activities, but such an approach

overlooks the challenges that students face while listening and may not help

them improve their listening skills.

Instructional activities consisting of a cycle of

listening, answering questions, and checking answers are really just testing

listening comprehension and do not help students learn how to develop their

listening skills and improve their listening abilities. It benefits learners if

teachers adopt a more balanced second (or additional) language instructional

approach that includes both process and product-oriented listening instruction

that teaches learners how to regulate their listening comprehension in addition

to assessing their listening skills (Vandergrift & Goh,

2012).

Compensatory Strategies

In addition to not being able to recognize or

comprehend the words they hear, multilingual learners often struggle with

listening because they do not apply “compensatory” strategies (Field, 2008).

Some examples of those strategies that would enable listeners to successfully

comprehend a passage include

- applying background knowledge,

- recognizing text types, and

- focusing on stress and intonation.

It is important to direct learners’ attention to

specific areas of the listening text for specific purposes. The goal is for the

students to gain a deeper understanding beyond basic comprehension, and, in the

process, develop their listening skills. The 11 strategies described in this

article are divided into two phases: the structured preview phase and the

selective strategic listening phase. For selected examples of these activities,

along with graphic organizers, see the Appendix.

Structured Preview Phase

Think of the structured preview phase as a movie

trailer that consists of a series of selected scenes from the film with the

purpose of attracting an audience. These excerpts are usually drawn from the

most exciting, funny, or noteworthy parts of the film, but they are shown in

abbreviated form and usually without producing spoilers. Similarly, the

structured preview phase of a listening passage consists of a series of

selected strategies that set up students’ expectations, motivate them, and give

them a focus for listening. The structured preview phase strategies help

learners adjust to the speaker’s voice, intonation, and pitch and also helps them

use cues to predict contextual meaning, establish emotional connotations, raise

awareness of sociocultural subtext, and attend to functional grammar.

Strategy 1: Adjusting to the

Speaker’s Voice and Preview of Content

Have students listen to the first few seconds of a

listening passage while reading the corresponding transcript. They guess what

the passage is about and share their answers with peers. Vandergrift (2004)

explains that the first few seconds of any listening text are challenging for

language learners. Inexperienced listeners need to adjust to the speaker’s

voice (articulation of sounds, stress, pitch range, loudness). This strategy

also previews the type of vocabulary, grammatical structures, and linguistic elements

that students will hear in the passage. The preview helps students employ

content and linguistic background knowledge to facilitate comprehension.

Strategy 2: Predicting Emotional

Overtone Strategy 2: Predicting Emotional

Overtone

Emotions are expressed differently by speakers from

various language and cultural backgrounds. “Cultural differences in emotions

appear to be due to differences in event types or schemas, in culture-specific

appraisal propensities, in behavior repertoires, or in regulation processes”

(Mesquita, 2003).For example, emotions of despair, happiness, depression, or

anger expressed by an American individual are different from those expressed by

an Arab, Korean, or Chinese individual. Identifying the emotional status of a

speaker helps students understand the speaker’s intentions and attitude.

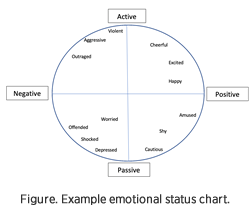

In this activity, have students listen to several

short segments while reading a script. As they listen, have them identify and

underline the content words spoken with the highest stress. They should guess

the reason for the speaker stressing those words and mark the speaker’s

emotions on an emotional status chart (see the example in the Figure). The

chart helps students to determine when the speaker is active, passive,

positive, or negative in delivering the message. (An internet search of

“emotional status chart” will show you a variety of formats.)

Strategy 3: Raising Awareness of

Cultural Elements

In this strategy, you select social, cultural, or

historical references included in a passage and ask your students to guess the

implication of each or search them on the internet. Students share their

information. Cultural elements can be places, events, social activities,

celebrations, and so on. This strategy helps students enhance their background

knowledge and situate a text in a sociocultural context, thereby improving the

meaning-making process when listening to the entire listening

passage.

Strategy 4: Attending to Functional

Grammar

This strategy directs students’ attention to the

role of grammar in building the meaning of a listening text. Listen to the text

and identify the common grammatical features used by the speaker. (The grammar

features form an essential component in constructing the intended meaning of

the text.) Have students listen to short segments that include the common

grammatical feature(s), and then have them transcribe the sentences, identify

the common grammatical features used, and indicate the intention of the speaker

for using them.

Selective Strategic Listening Phase

So far, we have focused on strategies that could be

used in the structured preview phase. In the selective strategic listening

phase, students delve more deeply into the content of the listening passage.

Knowing your students and your listening text, you decide on the most

appropriate strategies to be used.

Strategy 5: Building a

Storyline

This strategy is useful for listening passages that

include a sequence of events, such as authentic news reports and stories.

Students listen to the passage and use a graphic organizer to indicate the

chronological order of all events stated or inferred: what happened first,

next, last.

Strategy 6: Paraphrasing to

Understand Inferencing

For this strategy, select a few key sentences from

the listening passage and paraphrase them with the same words but different

word order—and hence different meanings. Students listen to the corresponding

original sentences, read the paraphrased sentences, and indicate which ones

mean the same and explain why. This strategy helps students understand nuances

and shades of meaning with a focus on syntactic formations.

Strategy 7: Recognizing Odd

Transcription

Prepare a partial transcript of a passage and alter

selected words or phrases. The new version has to make sense so that the

changes are not too obvious. The key is that the altered transcript must be

comprehensible. Students listen and underline the odd transcription while

listening. Next, they listen for a second or third time to correct the

transcription.

Strategy 8:

Paragraphing Strategy 8:

Paragraphing

Audio or video presents ideas in chunks—or

hypothetical paragraphs. Each “paragraph” provides a specific meaning that

contributes to the overall contextual meaning. In this strategy, students

listen to a passage and, whenever they think the speaker is starting what seems

to be a new paragraph, write three or four words that they can hear. Allow

students to listen to the passage again, check their paragraphs with one

another, examine how each paragraph is linked to the previous one, and make

brief notes about what the speaker is saying in each paragraph. Students may

need to listen to the passage several times to complete the task. This strategy

helps students follow the speaker’s development of thoughts.

Strategy 9: Distinguishing Between

Facts and Opinions

For this strategy, use a graphic organizer with two

columns: facts vs. opinions. Have students listen to an excerpt from the

passage and compose a list of facts and opinions. Then let them explain their

answers.

Strategy 10: Identifying

Referents

Almost all pronouns challenge inexperienced

listeners. They are difficult to detect in speech and it is difficult to track

their referents, especially if they appear attached to verbs, nouns, particles,

or prepositions. To help students identify the referents of pronouns, have them

listen to a passage, read transcripts of short extracts where pronouns are

used, and write the referent of each as indicated in the listening

passage.

Strategy 11: Building a Comprehensive

Summary

Teachers often ask students to listen to and summarize

a passage, overlooking the difficulty of the summary task. Summarizing requires

grasping the meaning; identifying key points; and restating them simply,

briefly, and accurately. This is a difficult listening task for inexperienced

multilingual learners. In this strategy, using a graphic organizer (see the

Appendix), students listen to a text in segments, each represented with a box,

and take notes in the box to specify the main idea of each segment. They may

need to listen repeatedly to add more information and build a comprehensive

summary.

Conclusion

Listening comprehension is a huge challenge:

The effective listener must comprehend the text as

they listen to it, retain information in memory, integrate it with what

follows, and continually adjust their understanding of what they hear in the

light of prior knowledge and incoming information. The processing imposes a

heavy cognitive load on listeners. (Thompson, 1995)

How can we help our students to be better

listeners? By helping them to be better prepared: They don’t have to understand

everything in the beginning. Draw their attention to specific areas of the text

for specific purposes. If we train our students to be active listeners by using

strategies in which they have to do something that gives their full attention

to the audio text, we can encourage active listening and help them develop the

practical listening skills they need to communicate in the real world.

References

Field, J. (2008). Listening in the

language classroom. Cambridge University Press.

Mesquita, B. (2003). Emotions as dynamic cultural

phenomena. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective sciences (pp. 871–890). Oxford

University Press.

Thompson, I. (1995). Assessment of second/foreign

language listening comprehension. In D. J. Mendelsohn & J. Rubin

(Eds.), A guide for the teaching of second language

listening (pp. 31–58). Dominie Press.

Vandergrift, L. (2004). Listening to learn or

learning to listen? Annual Review of Applied Linguistics,

24, 3–25.

Vandergrift, L., & Goh, C.

(2012). Teaching and learning second language listening:

Metacognition in action. Routledge.

Jon Phillips is currently a senior faculty development specialist at the Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center (DLIFLC) in Monterey, California, USA. Previously, he worked with Peace Corps in Ghana and Nepal; World Learning in Indonesia, Thailand, and Bangladesh; Egypt’s Binational Fulbright Commission; America-Mideast Educational and Training Services (AMIDEAST) in the UAE; the Center for International Education; Care International; American Institutes for Research (AIR); and U.S. State Department’s English Language Specialist Program in Kenya and South Sudan.

Federico Pomarici is a senior faculty development specialist at the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California, USA. He has taught Italian language and has worked in private and public educational environments, such as Oxford University Press, Middlebury College, and Monterey Institute of International Studies. He enjoys active life and the outdoors.

|