|

The term vulnerable learner is

becoming more commonly used, but what does it mean? Who are these learners, and

why are they “vulnerable”? For the purpose of our work, we use the definition

developed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD),

which states that a vulnerable learner is any student with one or more of

the following identifiers: has a lower socioeconomic background, special needs, or a diverse gender, or is a language learner or minority (Reimers &

Schleicher, 2020).

Any one of these factors may impact a student’s

educational achievement because it acts as a barrier to their ability to focus

on educational learning without strong classroom and school support. Many

language learners within our schools have more than one factor that places them

at risk of failing academically, which has been exacerbated due to the COVID-19

pandemic. For vulnerable learners, the impact will be significantly more

devastating.

Issues Facing Vulnerable Learners

Multicultural students come into our classrooms

with diverse backgrounds that must be acknowledged by the teacher and school.

Although perhaps well-intentioned, misguided actions that minimize the cultural

and linguistic assets of multicultural students (e.g., giving every student an

“American name” or lumping all Spanish speakers together as “Hispanic”) result

in vulnerable learners not feeling like individuals, and not feeling socially

and emotionally supported.

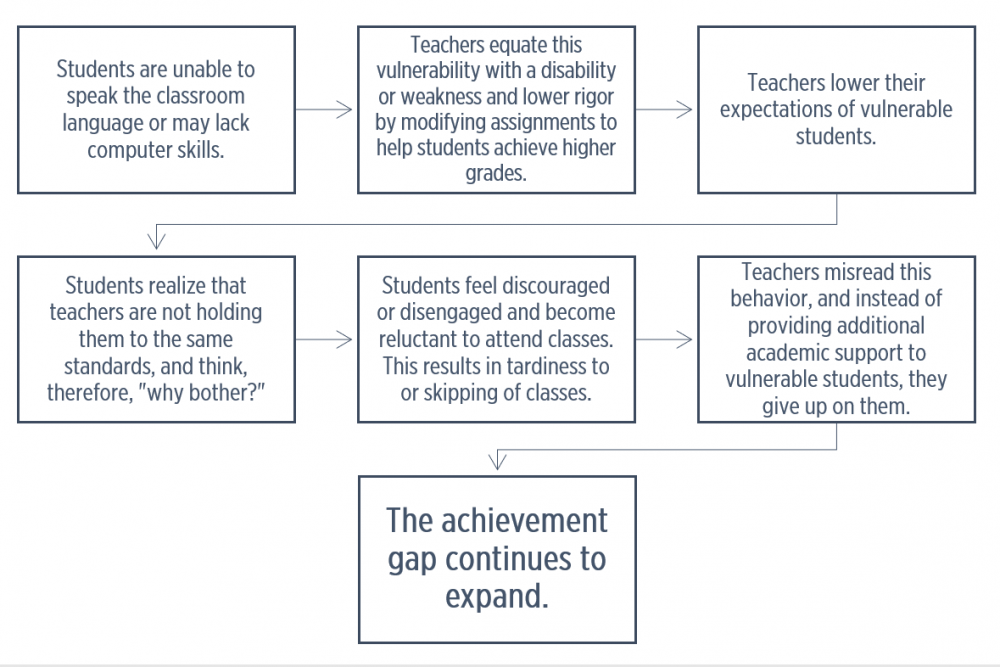

There are several teacher actions that can lead to

undesirable student responses, and these can, in turn, lead to negative teacher

perceptions; it is an unfortunate cycle. Here are some examples of such

behavior and the damaging cycle that results in a spiraling toward a widening

achievement gap (see Figure 1):

Figure 1. Expansion of the achievement gap for

vulnerable students.

Click here to enlarge.

Lowering rigor puts already at-risk students in a

position of falling even further behind their peers without a clear path to how

that gap will be closed.

At a school wide level, vulnerable learners are

often educationally disengaged. They might question the value of going to

school, as many of them have experienced continued failure in multiple

settings. This disengagement is demonstrated in tardiness and inappropriate

behavior. Language learners and those with a disability may also struggle to

focus on multistep directions, questions, or activities. Rather than reveal a

lack of confidence or ability or show their sense of exclusion, many vulnerable

learners would prefer to misbehave and skip classes. Adults, then, perceive

that these students lack motivation, and therefore, do not want to learn.

However, by the secondary level, vulnerable

learners are not motivated to keep trying in a system designed to keep them

from succeeding.

These observable behaviors are universal across

school districts, states, and countries. The question that needs to be asked

is: How do we identify these behaviors for what they are and create an

environment where these learners can feel secure knowing that our schools will

help them? The changes that classrooms and schools may need to make are not

expensive and do not require the purchase of a new program. They just need the

dedication of teachers and administrators to create an equitable space for all

learners.

Strategies and Supports That Can Lead to Success

Creating an environment that is all-inclusive and

accepting of diversity will result in a welcoming space, which students can

easily recognize. This can happen concurrently with the school and community,

as well as the classroom.

In the School and

Community

Reengage School and Community. Creating an equitable space begins with the school and community.

Administrators can set the tone by helping their school and community reengage

with each other as well as taking the time to collaborate and engage with

teachers. According to Siler (2020), “The best solution is often found after

seeking information and engaging in dialog and thoughtful deliberation” (p.

108). These do not have to be in-depth sit-downs, but they can be conducted

through daily and/or weekly interactions making use of emails, short phone

calls, or quick drop-ins, both with teachers, parents, and the community.

Similarly, schoolwide initiatives that involve teachers, community, and parents

as valuable members of the learning team will also lead to increased dialog

between teachers and families. Families should be recognized and used as a part

of the team.

Set a Tone of Rigor.

Administrators can also set the tone for how vulnerable learners are perceived

academically in their schools. Building and supporting a demand for a rigorous

curriculum goes a long way toward developing a school culture that emphasizes

that all students can learn. Teachers can feel that they are being supported to

push their students to their full potential and that their administrators will

support them with job-embedded professional development, resources, and

materials to reach all of their students. Set a Tone of Rigor.

Administrators can also set the tone for how vulnerable learners are perceived

academically in their schools. Building and supporting a demand for a rigorous

curriculum goes a long way toward developing a school culture that emphasizes

that all students can learn. Teachers can feel that they are being supported to

push their students to their full potential and that their administrators will

support them with job-embedded professional development, resources, and

materials to reach all of their students.

Provide Extended Learning

Opportunities. Purposefully scheduling extension and extended

learning opportunities for all students increases equitable learning. Adequate

time should be designed in the schedule for small-group instruction,

high-dosage tutoring, and 1:1 instruction, as needed. This can be done during

the school day as well as before and after, or even on the weekends.

Implement Restorative

Practices. Last, but not least, it would be remiss not to talk about

restorative practices (see www.iirp.org) and the need to take

a step back from traditional and punitive practices when dealing with student

discipline and infractions. “Restorative practices in schools create a healthy

atmosphere that supports positive development, teaching, and learning” (Brown,

2018, p. 7). Social and emotional support for the whole school are just as

important as academic needs.

In the Classroom

Create a Rigorous and Supportive

Classroom Environment. Invoking an equitable space for all students

in the school also demands that teachers design their classrooms with a similar

focus. A rigorous, grade-level curriculum needs to be the standard, along with

high expectations and academic support. Classrooms should be learner-focused

spaces where students can struggle and work with the curriculum as well as each

other, but also know that scaffolds and accommodations are in place as needed.

Students are the focus of the class, not teachers. The expectation should be

clear that students will articulate what they are learning with each

other.

Create a Safe and Trusting Classroom

Environment. Unquestionably, classrooms need to become places where

students can receive restorative strategies and support. It is key to teach

students the fundamentals of restorative practices so that when a conflict

occurs, all involved parties can move towards repairing relationships.

Restorative practices create spaces “…where students, teachers and staff want

to be; where they feel safe, trusted, and accepted; and where they experience

care and belonging” (Brown, 2018, p. 7). Challenges will occur, but our vulnerable learners need to learn how to reenter the

classroom after a conflict and move forward.

When teachers are enacting the aforementioned

strategies and supports, the classroom becomes a true place of learning for

all. Learners are taught to celebrate mistakes, assume the best, and applaud

their awesomeness (Boynton & Moore, 2021).

Conclusion

Students who are vulnerable learners are

increasingly falling behind in schools, but when school administrators,

teachers, and the community work together, these learners can achieve. Focus

needs to be placed upon academics as well as positive social-emotional

learning. It begins with administrators placing trust and support in their

teachers. When the staff begins to feel the positive efficacy from the

leadership team and know that they are valued members of the school, it can

trickle down to how they perceive the learners in their classroom. This, in

turn, will promote a positive classroom climate that promotes social as well as

academic success.

References

Boynton, M. J., & Moore, J. (2021, November

4–6). Creating equity for vulnerable learners [Conference

presentation]. Association for Middle Level Educators, Virtual.

Brown, M. A. (2018). Creating restorative

schools: Setting schools up to succeed. Living Justice Press.

Reimers, F., & Schleicher, A. (2020). Schooling disrupted, schooling rethought. OECD.

Siler, J. M. (2020). Thrive

through the five: Practice truths to powerfully lead through challenging

times. Dave Burgess Consulting.

Dr.

Jana Moore is a teacher on special

assignment and program lead at Parkside Middle School in Manassas, Virginia,

USA. Her foci include long-term English learners and vulnerable learners. In

her current capacity, Dr. Moore works as an instructional coach to provide

teachers with direction in creating equitable classrooms for these

learners.

Dr. Mary Jane

Boynton is principal of Parkside Middle

School in Manassas, Virginia, USA, in her 30th year in education and her 16th

year as an educational leader. Under her leadership, Parkside became a

Cambridge International School and Cambridge International Professional

Development Site. Dr. Boynton provides a wide variety of professional learning

opportunities to educators, with the focus on teaching and learning, bilingual

education, digital literacy, and educational leadership.

|