|

I

have been teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) in different university

contexts since 2010. Most of my teaching career was in Turkey. Teaching in

general and teaching languages, in particular, is a curious profession. Most of

the time, we, teachers, are underpaid, we overwork, and we may find ourselves

working in difficult conditions. Similar problems that lead to language teacher

burnout are highlighted in previous research (e.g., Acheson et al., 2016). On

the other hand, teaching comes with great rewards. There are many driving

forces that teaching provides, such as seeing the joy of my students when they

achieve beyond their expectations, their everlasting gratitude, and the

kindness you receive from them in return—these are some of the rewards that

have kept me going. I

have been teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) in different university

contexts since 2010. Most of my teaching career was in Turkey. Teaching in

general and teaching languages, in particular, is a curious profession. Most of

the time, we, teachers, are underpaid, we overwork, and we may find ourselves

working in difficult conditions. Similar problems that lead to language teacher

burnout are highlighted in previous research (e.g., Acheson et al., 2016). On

the other hand, teaching comes with great rewards. There are many driving

forces that teaching provides, such as seeing the joy of my students when they

achieve beyond their expectations, their everlasting gratitude, and the

kindness you receive from them in return—these are some of the rewards that

have kept me going.

These rewards, however, along with the challenges, also result in the

building up of an emotion labor for teachers (Gkonou & Miller, 2021).

Emotion labor is defined by Benesch (2018) as “conflict[s] between implicit

institutional feeling rules and discourses of teachers’ training and/or

classroom experience” (2018, p. 63). According to her poststructural stance,

emotion labor is a dynamic notion and can be a possible tool of activism and

agency. Emotions, ours and our students’, are integral to our profession.

Positive emotions can contribute much to our everyday practice. Nevertheless,

our language classrooms do not take place in a void. We are not living in a

wonderland, and, oftentimes, the volatile world with all its turmoil

infiltrates into our classrooms either through our students’ emotional states

or ours, which is also quite normal.

One thing that has become apparent to me in my teaching career is that

it can be very challenging to be an adolescent language learner. The year 2019

was a particularly stressful one for those working and studying at Turkish

universities. In Turkey, there was a sudden rise in the suicide rate,

particularly among young people, according to news

reports (Hürriyet Daily News, 2020). This phenomenon did not leave

the university unscarred. A conversation that I had with a colleague was

particularly thought provoking for me; she told me how powerless she felt and

that she had no idea what her students had been going through.

Revising the Language Classroom Ecology Through Action

Research

Reflecting on her words, I decided to increase my understanding of my

students’ experiences and emotions by creating a classroom ecology where

learners were motivated to speak about their lives. Social-emotional learning

(SEL) provided a blueprint for me in designing my EFL speaking module.

According to SEL, designing programs and lessons that promote learners’ social

and emotional competencies are of critical importance. Accordingly, the

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL; 2013)

proposes five competencies:

- self-awareness

- self-management

- social awareness

- relationship skills

- responsible decision-making

In English language teaching, aiming to develop language learners’

competencies to use language more effectively to better understand their

feelings is of critical importance because language is a “tool for the

restoration, support, and healing of [English learners]” (Pentón-Herrera, 2020,

p. 6). With that in mind, I used CASEL’s competencies to design a participatory

action research intervention that included EFL speaking tasks related to my

students’ everyday challenges—these activities urged students to scrutinize

stressful social situations and work together to find solutions using the

target language.

Overall, participating students reported that they felt more engaged

once they had opportunities to speak about their lives in the target language.

I have recently published this practitioner research (Uştuk, 2022) here.

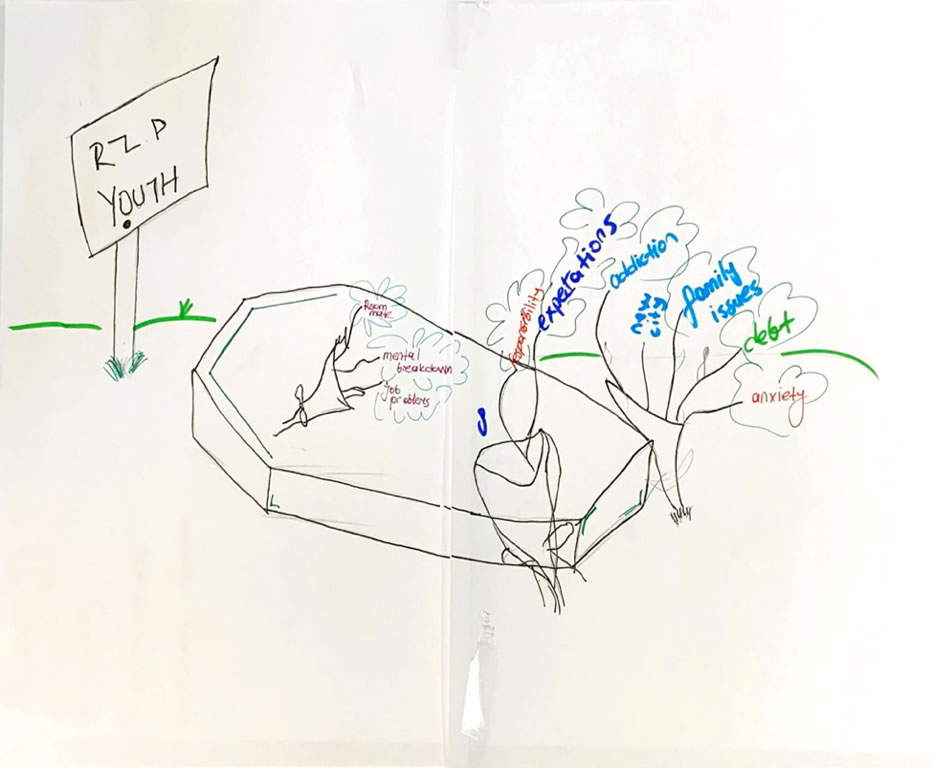

Figure 1. Student work: “Rest in peace youth.”

(Click here to enlarge)

Figure 1 shows a poster that one group of students produced. Using

the

mantle of the expert, a generic drama-in-education technique that is

often associated with famous drama educator Dorothy Heathcote, the students

take on the role of experts in a field; in this case, they took on the role of

youth workers. These youth workers were the experts invited to investigate the

youth problems in a town. After a series of interviews (some students taking

the roles of interviewers, others the interviewees; they relied on the dynamic

role shifts and the flexibility of drama-in-education), this poster (Figure 1)

was one group’s work illustrating what kind of problems the young people in

this town experienced. It shows a daunting, even shocking metaphor of a graveyard.

(The flowers resting on the grave in the figure read: roommate, mental breakdown, job problems, responsibility, expectations, addiction, new city, family issues, debt, and anxiety.)

This was just another signal for me as the teacher to understand how

the events in 2019 and 2020 influenced my students. The findings of my action

research showed that learners felt “honored” and “respected” to talk about these

authentic issues affecting their lives on an everyday basis. As a language

educator, the whole experience of using the target language as a tool, as

Pentón-Herrera puts it, for “restoration, support, and healing” of my learners

(2020, p. 6) was a fulfilling one. This was just another signal for me as the teacher to understand how

the events in 2019 and 2020 influenced my students. The findings of my action

research showed that learners felt “honored” and “respected” to talk about these

authentic issues affecting their lives on an everyday basis. As a language

educator, the whole experience of using the target language as a tool, as

Pentón-Herrera puts it, for “restoration, support, and healing” of my learners

(2020, p. 6) was a fulfilling one.

3 Takeaways as a Language Teacher

To conclude, I would like to briefly reflect on my action research

experience. Engaging in this practitioner research helped me to learn about my

students’ lives and afforded me three takeaways as a language

teacher:

1. Awareness: We teachers need to have a

way to systematically take learner emotions into account in our teaching. We

also need to use language as a tool for our students to better understand their

emotions, which are mostly related to happenings beyond our classroom doors. An

SEL framework helped me to do that.

2. Authenticity: The topics and concepts

I ask my learners to engage with need to be relevant to their lives. This is

not only about making our linguistic content more relevant to their practical

needs but it is also humanizing our pedagogy and it is a matter of

respect.

3. Achievement: Doing practitioner

research helps me become a better teacher (e.g., by making my lessons more

engaging). It also makes language teaching more fulfilling and less stressful

as I better understand what is happening in and around my class.

Note: This article is an extended version of a

TESOL Blog post (here)

that was published as a part of the TESOL Research Professional Council (RPC)

Blog Series. You can find more

blog posts from the RPC.

References

Acheson, K., Taylor, J., & Luna, K. (2016). The burnout

spiral: The emotion labor of five rural U.S. foreign language teachers. The

Modern Language Journal, 100(2), 522–537. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12333

Benesch, S. (2018). Emotions as agency: Feeling rules, emotion labor,

and English language teachers’ decision-making. System,

79, 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.03.015

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (2013). Effective social and emotional learning programs.https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED581699.pdf

Gkonou, C., & Miller, E. R. (2021). An exploration of language

teacher reflection, emotion labor, and emotional capital. TESOL

Quarterly, 55(1), 134–155.https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.580

Hürriyet Daily News. (2020, November 20). Suicide rate

increases in Turkey, report reveals.https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/suicide-rate-increases-in-turkey-report-reveals-160170

Pentón-Herrera, L. J. (2020). Social-emotional learning in TESOL:

What, why, and how. Journal of English Learner Education, 10(1), 1–16.

Uştuk, Ö. (2022). ‘This made me feel honoured’: A participatory action

research on using process drama in English language education with ethics of

care. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and

Performance, 28(2), 279–294.https://doi.org/10.1080/13569783.2022.2106127

Özgehan

Uştuk is an EFL teacher, teacher educator,

and researcher. He currently works at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University as a

postdoctoral researcher. He has worked as an EFL teacher along with his

research career in Turkey. His research areas include drama-in-education, TESOL

teacher education, professional development, identity, and emotions. He has

conducted several practitioner research projects in different forms, such as

action research, exploratory practice, and lesson study. |