Many multilingual learners of English face stress and/or anxiety, not just about learning a new language but also about their personal narratives—the aspects that rest beneath the surface of what they might demonstrably show. Though adopting a mindfulness practice in the classroom can take place at any point, doing so at the beginning of a new year provides an ideal opportunity to develop new habits and implement practical techniques that can leave a lasting impact on one’s learning experience. As an English language lecturer and conflict resolution practitioner, and with the perspective that pedagogy and practice inform each other, I suggest approaching the issue of student stress and anxiety with five mindfulness techniques:

- Gradual exposure

- “I feel” statements

- Four elements of stress reduction (Shapiro, 2012)

- Self-scan, awareness, and containment

- Reframing automatic negative thoughts (ANTs; Amen, 2015)

Note: It is well worth noting the adage, “One cannot pour from an empty cup.” Check in with yourselves first and make sure your proverbial cup is filled—enough that you can pour out for your students. (Of course, this directive is easier written than done, in practice.)

Because stoicism is often both a geographical and academic cultural norm, prioritizing and modeling practical methods for mental health inclusivity supports a classroom environment that truly teaches the whole person.

The framework for these techniques should be led with the following motto: Progress over perfection. Normalizing conversations about stress and anxiety in the classroom promotes and sustains a learning environment where students prioritize their well-being in relation to learning. It is most effective to introduce the following techniques as early as the first few weeks of your academic context, but it is beneficial at any time.

For each technique, I've provided guiding objectives and principles so you can adapt the techniques to your audience and level.

Technique 1. Gradual Exposure

Guiding Objective: The purpose of gradual exposure is to incrementally become comfortable with experiences that cause discomfort and resulting stress or anxiety.

Approach

-

Have students identify one task or aspect of the course or class that would typically cause them direct or indirect stress or anxiety.

-

Then, have students brainstorm as many achievable microgoals as possible—microgoals that would support them with stronger feelings of ease along with the stressful event. Map the microgoals in order from least stressful to most stressful, with the final stressful event at the top.

-

Teach students that the goal is to make progress, and if they were only able to surpass their first microgoal, even that would be progress.

-

Provide an example (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Gradual exposure example.

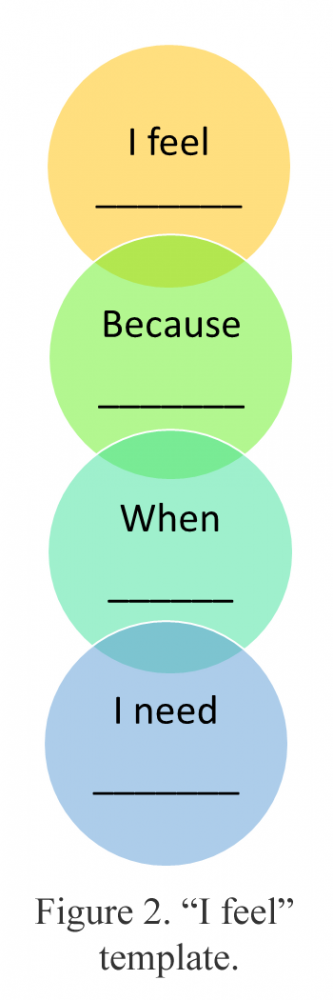

Technique 2. “I feel” Statements

Guiding Objectives: “I feel” statements establish ownership of one’s feelings and consequently initiate personal accountability. The goal is to normalize talking about how students feel in relation to stress and/or anxiety, explore why they might feel that way, and support an environment where they express what they need.

Approach

Approach

-

Establish a regular practice of “checking in” with how students feel about a class-related task, happenstance, or event.

-

Consider having an “I feel” poster in your classroom or a section in your course syllabus.

-

Teach how to effectively express “I feel” statements using a template similar to the one shown in Figure 2.

-

Provide examples:

Example 1

I feel anxious because I don’t think my language ability is good enough to deliver a presentation.

When I speak in public at my level of ability, I stutter and even forget what I am supposed to say.

I need more practice and to feel comfortable making mistakes as I grow.

Example 2

I feel frustrated because I studied very hard for my reading comprehension/oral communication exam, and I earned a grade lower than I expected.

When I see my grade lower than where I think my progress is, I feel like giving up.

I need to practice having a growth mindset, to understand that progress is not linear, and to believe that I am going to eventually achieve my goals.

Technique 3. Four Elements of Stress Reduction (Shapiro, 2012)

Guiding Objectives: Shapiro’s (2012) four elements of stress reduction—earth, air, water, and fire—promotes the practice of keeping your stress levels within a window of tolerance by implementing four grounding exercises that redirect attention outward and inward. The intention is to, in each part of your body (see Figure 3), work through moments where you feel flooded by feelings of stress tied to a class-related event through acknowledgement, acceptance, and release.

Approach

Figure 3. Anatomical view of Shapiro’s (2012) four

elements of stress reduction.

-

In the early weeks of an academic session, introduce students to the concept of self-regulation and emphasize the importance of checking in with oneself.

-

Underscore the principle that self-checks are a form of self-respect and self-care—both being characteristics of resilient and motivated lifelong learners.

-

Teach students how to do Shapiro’s four elements using an example like the following:

Example

Teacher: Acknowledge stressful feelings and self-regulate by doing as many of the four steps as you can:

1. Earth: Get grounded by connecting with the earth. This could be taking your shoes off and taking a barefoot walk, even if it is brief. Or, getting grounded could be tapping your feet to a rhythm that is comforting. Even bolder, ground yourself by putting on your favorite song and dancing. The idea is to move.

2. Air: Breathe by putting your left hand on your heart and your right hand on your stomach and inhaling for four counts and exhaling for seven counts. The idea is to slow down your nerves, and connecting with your breath is most effective.

3. Water: Taste something that will liven up or refresh you. This could look like drinking a cup of comforting tea or sucking on a peppermint candy.

4. Fire: Imagine your safe and happy place. As you pull up this image in your mind, place yourself in it and think about how you feel when experiencing your comforting space. Allow yourself to dwell on that thought for a minute before repositioning yourself in your circumstance or environment.

Technique 4. Self-Scan, Awareness, and Containment

Guiding Objectives: Psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk (2014) is known for saying “The body keeps the score.” A body that keeps the score, a dysregulated body, is often unmotivated to learn because it is under duress. By teaching students the practice of drawing awareness to how one is feeling, they can then learn how to direct feelings to an appropriate place in one’s experience—a form of containment. Cultivating an atmosphere where acknowledging how students feel in the classroom as a regular component of the day’s agenda brings balance to the era of “leave your feelings at the door” in education and academia.

Approach

-

Be in tune with your class and make it a conscientious point to take the social-emotional pulse of your students as they enter. This might look like making eye-contact and addressing students by name as you welcome them to class. Look for verbal and nonverbal cues to determine whether this mindfulness technique is appropriate for the day.

-

Consider adopting a mindfulness warm-up practice in the first 10 minutes of class where you walk students through a body scan. Here is an example:

Example

Teacher: Good morning. Welcome to class. I invite you to participate in a brief warm-up before we dive into our lesson today. Participation is optional. If you choose not to participate in our warm-up, take these next 5 minutes to center (focus) yourself ahead of our time together.

Self-Scan and Awareness

Are we ready?

Close your eyes in 5, 4, 3, 2, 1.

Ease (become comfortable) into your seat and into this classroom.

We’ll begin by becoming aware of our breath.

At your own pace, take three breaths. Inhale (breathe in) and slowly exhale (breathe out). [Wait 5 breaths.]

Become aware of any tension or discomfort you might feel. What is weighing you down today? What might be occupying your thoughts?

Containment

As you become aware of how you are feeling, acknowledge yourself and direct those feelings to where you want them to go. This could be in a container on a shelf or even in box that you dump in an ocean.

Remind yourself that you can always revisit what is bothering you or occupying your thoughts at any time, but that you are choosing to acknowledge and contain them for our class time together.

Closing

Once you have directed your feelings to where you want them to go during our time together, take three breaths at your own pace. [Wait 5 breaths]

Now, open your eyes in 5, 4, 3, 2, 1.

Technique 5. Reframing Automatic Negative Thoughts (ANTs)

Guiding Objectives: Conceptually designed from the work of Beck et al. (1979) and later coined and further developed by psychiatrist Amen (2015), the term “automatic negative thoughts” (ANTs) refers to the proliferation of one’s long-held automatic negative beliefs. Students often curate narratives of what they might have been told their strengths or weaknesses are in a subject or academic history and use those frames for how they position themselves in class and how they see themselves as independent language learners. Whether the negative thought be categorized as catastrophizing, labeling, mind reading, or blaming—just to name a few ANTs categories—the thought presents a cognitive distortion that needs reframing so students can progress. The objective is first to help train the mind to identify ANTs and afterwards, to reframe them.

Approach

-

Teach students the concept that our brains believe what we tell them and, like anything else, the brain becomes what we feed it. So, it is best to feed it a great diet.

-

Briefly walk students through a reframing ANTs exercise like the following:

Teacher: We often have ANTs that can influence how we view ourselves and even learn and grow. For me, your professor, this is what my ANT sounded like: “I’m not good at math. I’ve never been good at math. I’ll never be good at math. So, I’ll stick to what I’m good at—reading and writing.” For someone learning a new language, an ANT might sound like this: “Others laugh at my pronunciation, so it is better if I stay quiet. If I don’t speak up, I will never be humiliated.” ANTs are like jokes—they only have a little bit of truth to them. ANTs are not the whole picture we want to believe.

Practice

-

First, take 1–2 minutes and write down one or more ANTs that often come up for you while in our class. You are the only person who is going to see your ANTs.

-

Then once you have your ANTs down, answer these questions about them:

-

My ANTs are 100% true all the time. ❏ Yes ❏ No

-

My ANTs define who I am. ❏ Yes ❏ No

-

My ANTs are the reality I want. ❏ Yes ❏ No

-

Chances are all your answers to the checklist above are NO!

-

Finally, write down what I like to call “positive encouraging thoughts” (PETs). PETs counter your ANTs. Your PETs are what you want to think about and believe. For me, my PET sounds like this: “Math can often be difficult for many people. Some concepts are easier than others for me to learn. Like other things that I learn, practice and progress are what I choose to believe I am capable of.”

-

For you, a PET for pronunciation skills while learning a new language might sound like this: “Learning and speaking an additional language proves how capable I am. I have language abilities that others may not have, and I am unique. My accent is part of who I am. Other people’s ability to understand me is what is important, not having perfect pronunciation. What people think about me is their problem—not mine.”

-

Repeat this process daily to avoid ANTs and keep PETs!

Conclusion

Often, teachers and students alike enter the classroom with conscious and unconscious assumptions of each other and the year or semester ahead. We must remember that our language learners enter our classrooms with an entire history of which we do not know, and stress and anxiety may very well be exacerbated by classroom happenings. The task at hand is clear—to provide multilingual learners of English with the knowledge and tools necessary to achieve learning gains and, hopefully, establish an environment in which they have ease and joy doing so.

References

Amen, D. G. (2015). Change your brain, change your life: The breakthrough program for conquering anxiety, depression, obsessiveness, lack of focus, anger, and memory problems. Harmony Books.

Beck, A. T., Rush, J., Shaw, B., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford Press.

Shapiro, E. (2012). 4 elements exercises

for stress reduction (earth -air -water -fire).https://emdrfoundation.org/toolkit/four-elements.pdf

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Mind, brain and body in the transformation of trauma. Penguin Books.

|

Download this article (PDF) |

Dr. Saghar Leslie Naghib, a second generation Persian American and Miami native, is a senior lecturer of English language with Duke Kunshan University’s Language and Culture Center and an advocate for normalizing the role of a positive mental health approach in education and academia.

| Next Article |