Reading is a vital skill in a university learning environment. International students, however, frequently underestimate its value based on the experience of preparing for standardized tests of English as a foreign language. As Rosenwasser and Stephen (2015) remind us, to move beyond reading for the gist and develop a deeper understanding of a text, readers should become more actively engaged with the text materials by talking about the reading conversationally with other people and being in “some kind of dialogue with it, to see the questions the material asks, and to pose your own questions about it” (p. 207).

Students engage in deconstructing a text by identifying the structural elements and linguistic features that are valued in a particular discipline (Cheng, 2018). They also exchange insights and negotiate roles while working together to construct meaning. In some cases, students may lead discussions among their peers by offering critical comments and asking challenging questions to uncover implicit meanings. This collaboration helps learners process a complex text by reducing the cognitive and emotional demands, which, ultimately, leads them to the realization that reading is a social activity (Su et al., 2018). Further, when a collaborative reading task is supported by technology, students’ interest and motivation to contribute in class activities increase.

In this article, we describe an activity called Collaborative Reading in a Virtual World (VW), during which students use their avatars in a virtual environment to discuss reading materials as a group. This activity was created to encourage students to critically read with their peers by discussing an assigned reading with one another in an environment where they feel comfortable sharing their thoughts and ideas. Benefits of collaborative reading include

- peer support,

- clarification of understandings,

- attention to details in a reading, and

- generation of new ideas.

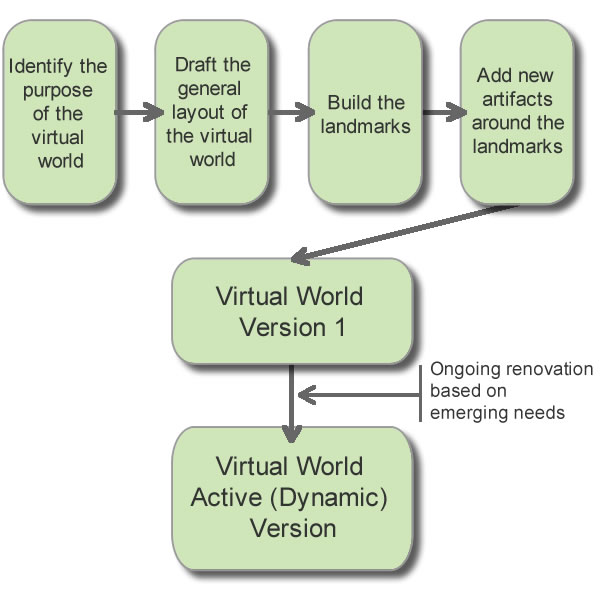

A VW is a more dynamic online environment than other conferencing tools because teachers can design the world based on the students’ emergent needs. For instance, a collaborative board can be built in the VW when students feel they need to take notes while discussing a reading. See Figure 1 for an example of a dynamic VW build around student needs and interests.

Figure 1. Screenshot showcasing a corner of our

departmental VW in which instructors can host end-of-semester

parties.

To conduct the collaborative reading activity, you’ll first need to create a VW and familiarize yourself with the world as you create it. Then, you’ll allow students to explore (or assign small tasks) to let them familiarize themselves with the VW before you assign the activity of collaborative reading.

1. Create a Virtual World

There are many different types of VWs available online; however, for the purpose of this activity, you’ll need a platform that allows users to build their own artifacts in the VW (e.g., Second Life or the Sims), because this affords various kinds of pedagogical activities. In addition, these platforms give the designers ownership of their designed worlds and can limit access to only eligible users.

Figure 2 depicts the process of creating a VW.

Figure 2. Steps to create a virtual world.

To create a VW that can be used for multiple classes, it is important to start with a clear objective. Once a theme is set, you can build the landmarks first, and small artifacts can be built around the landmarks based on the functions of the landmarks and the layout of the region.

An ideal VW is dynamic—it can be constantly updated based on emerging needs. For example, if you plan to hold a virtual presentation session, you can build conference rooms, interactive screens, tables, and chairs in one or several of the buildings you’d already built in the VW.

Although the creation of a VW might seem a daunting task, language teachers have many options:

-

Create a simple VW with fewer artifacts for your own classes.

-

Form a team with other teachers; work together to create a comparatively complex VW and share the virtual space for different purposes.

-

Involve students in cocreating a VW.

2. Let Students Explore

To maximize the benefit of collaborative reading in a VW, students must be familiar with the relevant technologies and prepared to meet with their peers in the world. Before beginning the activity, you can help students become familiar with all the basic functions inside a VW, such as

- talking using an avatar,

- moving around (walking, running, and flying),

- teleporting to different locations, and

- using embedded collaborative boards or other tools.

Once students become adept at the VW technologies, you can model how to read collaboratively in a VW.

3. Assign the Collaborative Reading Activity

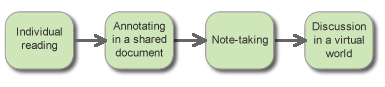

There are several key steps in this activity for students to make meaningful contributions to the joint discussion. Collaborative reading in a VW generates a learning process (see Figure 3) in which students read individually first, annotate in a shared document, and then take thoughtful notes that end with discussion in the VW.

Figure 3. Collaborative reading process.

Preread and Annotate

It is essential for students to read individually in advance so that they can formulate questions to discuss with their peers when they meet in the VW. Divide students into groups of three to four and have each group annotate a reading using different colors in a collaborative document, such as in Google Docs. Annotations are key in this activity because they prompt students to ask each other questions. When students meet in the VW and look at the annotated reading, they can see how they annotated differently, and these differences in annotation will lead to conversations about their understanding of a reading.

Take on Roles

Students may take on different roles in the joint task; assigning these roles can ensure active participation from each person. For example, one student can be a lead discussant while other students can be assigned to summarize main points raised by their peers or become word masters (defining unfamiliar terms). Another responsibility may be to provide an in-depth commentary on a selected passage.

Discuss the Reading

When students meet in the VW, they will teleport to a location they have agreed upon before the meeting where they will be able to see a collaborative board on which everyone can write while discussing. The group member whose role is to lead the discussion can begin by listing the questions each member had about the reading.

Figure 4 captures a group engaging in collaborative reading in the VW; the group was discussing the concept of “deepfake” that came up from the reading material. Record the collaborative reading sessions for further reflections as a postreading activity.

Figure 4. Screenshot of a collaborative reading

session.

Other Uses for Virtual Worlds

A VW has many potential uses in language learning classrooms. Once you’re comfortable as a VW designer and know what things your students relate to, you can create meaningful spaces with different function-carrying artifacts based on the needs of your students and your classroom activities.

In addition to reading, you can also use VWs for writing and public speaking. Some activities include

- designing a writing process in a group,

- group free writing,

- mock public speeches, and

- debates.

Conclusion

Based on student feedback, collaborative reading in a VW has been shown to be effective in our reading classes. Students enjoy the novelty of using their avatars to read with their peers. Instead of treating reading as an individual activity, they embrace the opportunity to participate in social regulation by providing input into one another’s annotations and sharing what they found interesting, confusing, and even frustrating about a reading. Because we asked students to record their virtual collaborative reading sessions, they reported that they were motivated to read an assigned article in depth to have a more robust discussion.

The process of discussing a text in a virtual space allows students to dialogue with the reading materials in depth and have more opportunities to think critically about the text, both in terms of ideas and linguistic choices to express them.

References

Cheng, A. (2018). Genre and graduate-level research writing. University of Michigan Press.

Rosenwasser, D., & Stephen, J. (2015). Writing analytically. Cengage Learning.

Su, Y., Li, Y., Hu, H., & Rosé, C. P. (2018). Exploring college English language learners’ self and social regulation of learning during wiki-supported collaborative reading activities. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 13(1), 35–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-018-9269-y

|

Download this article (PDF) |

Lin Zhou is an assistant teaching professor in the NU Global program of Northeastern University. Specializing in pedagogical game design and innovative course design, Dr. Zhou promotes and practices teaching that revolves around experiential learning, project-based instruction, and game-supported pedagogies. A frequent speaker at international conferences, she has presented papers on topics including language learning with an augmented reality mobile game, translanguaging in pedagogical drama gaming, and an ecological approach to an online second language writing course.

Natalya Watson holds a master’s in TESOL from Northern Arizona University and a doctorate in education from the University of Colorado Denver. She teaches in the Global Pathways Program at Northeastern University of Boston. Her research interests include academic literacy of second language learners, genre analysis, and English for specific purposes. She frequently presents her work at TESOL and AAAL.