|

EAP programs begin with Needs Assessments (Benesch, 2001;

Brinton, Snow & Wesche, 2003; Bruce, 2011; Hyland, 2006) of

where students are (present situation analysis) and where they need to

go (target situation analysis) (Benesch, 2001; Bruce, 2011; Hyland,

2006). We, as EAP professionals, are concerned with bridging the gap

between students’ current language proficiency to that which is required

for academic success. As such, there is a large body of research to

identify those needs (Benesch, 2001; Bruce, 2011; Hyland, 2006).

Moreover, I do not think anyone would disagree that EAP is high-stakes.

My context is such. I teach in an intensive, pre-sessional EAP

program at the advanced level. Our curricula are based on the language

and skills ‘needed’ for post-secondary programs. Most of my students are

international pre-undergrads who have been in Canada fewer than 4

months and are on their own for the first time.

Given our SLA knowledge, needs analyses, and what is at stake,

why do some of our students display ineffective learning behaviours? In

our quest as EAP professionals to define the academy and its English,

sometimes the person has been lost. Although there

are many factors involved in adult SLA success (or not) such as aptitude

and affect (Gregerson & Horwitz, 2002; Horwitz, 2001),

motivation (Dörnyei, 2001), and L1 proficiency (Sparks &

Ganschow, 1991, 1995), intercultural experiences are the focus of this

article.

Personal Interest

I had the opportunity to move to a small village in Austria

after taking German as a foreign language for only 6 months. The

experience of total language and cultural immersion was eye-opening. I

now understand that my EAP students not only face language issues, but

they also face socio-cultural issues that can be more pressing than

academic vocabulary or note-taking. Adopting a new culture, temporarily

or permanently, causes more immediate issues than simply learning

language, and sometimes life’s social needs will take precedence over

academic language needs. One need only go back to Maslow’s Hierarchy of

Needs to find explanations for unproductive classroom behaviours that we

sometimes assume to be a lack motivation.

Although I am applying these issues to my EAP context, I

believe what I am saying also applies to community ESL programs. My

personal examples stem from my experience as a recent immigrant and not

as an academic. The experiences in this article are anecdotal; my goal

is to raise awareness and understanding of intercultural experiences

that could affect classroom behaviours.

Theoretical Framework

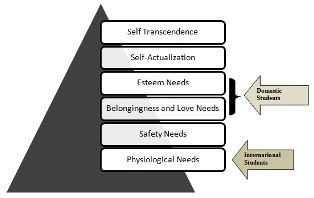

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (see figure 1) requires the lower

levels to be fulfilled before attainment of the higher level needs can

begin (Owens & Loomes, 2010). Owen and Loomes (2010) contend

that international students are generally at the bottom of the hierarchy

whereas domestic students are at the levels associated with

post-secondary studies (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. (Based on Owens & Loomes, 2010).

Furthermore, I would argue, domestic students are concerned

with Belongingness and Esteem Needs predominantly within the academy as

they are already members of the dominant society. International

students, however, not only additionally face Physiological and Safety

Needs, they are facing Belongingness and Esteem Needs in the ‘new’

society and also within the academy.

Hierarchy Affecting Learning

Physiological needs are the most basic, and if they are not

met, it is difficult to focus on anything else. While my EAP students

have the basic needs, as I did, this does not mean that there are no

issues. To illustrate, the food in Austria is good but different from

what I was used to. I suffered some gastro-intestinal distress while my

body adjusted; I was quite uncomfortable some days. Additionally, some

students have explained to me that Canadian meal sizes and times are

quite different from those in their countries. For students staying with

host-families, hunger in the classroom can occur as they may be used to

larger breakfasts or lunches and smaller dinners than is the Canadian

custom. It is not their house, so they often do not explain this to

their host-families and simply come to class hungry. It is difficult to

concentrate on what makes a good thesis statement when you are

uncomfortable or hungry.

Maslow’s Safety Needs entail adjusting to a new/no family

environment (figure 1) and having a sense of security (Owens &

Loomes, 2010). In my experience, social networks offer a sense of

security. I, like many of my students, left my family behind. I moved to

Austria with only my husband, who worked full time. I ‘knew’ adjusting

would be difficult, but I had no idea how difficult. My first few months

were fraught with fear. I did not feel completely secure in my

apartment or with my health because I worried that an issue would arise,

and I would not be able to explain it. I drove, so my husband got me a

cell phone. I still did not feel completely secure: What if I got a flat

tire? I didn’t know that vocabulary! And what if I got into an

accident? How would I explain? There have been many times that students

have requested a meeting with me only to ask about very personal medical

issues or legal contracts (ie: apartment leases) instead of course

content; they have no idea where to go or what to say, and they are

worried and/or scared. I suspect that many more of my students are also

experiencing similar anxieties, and although there is an optimal level

of anxiety that can foster performance, too much can be debilitating.

Once safety has been established, Belongingness (figure 1) is

next: wanting to feel accepted and being able to communicate effectively

(Owens & Loomes, 2010). In my experience, the former can work

against the latter. The first few months in Austria, I felt detached, so

I sought out English speakers, and I mostly watched CNN. This did not

help my German and I knew it, but I felt less detached. A ‘common’

comment I hear is ‘their English would improve faster if they didn’t

switch to L1 as soon as class is over!’ Clearly, this practice does not

foster L2 acquisition (Owens & Loomes, 2010), but as

international students “...commonly experience comprehensive social

separation and isolation...” (Owens & Loomes, 2010, p.276), it

does help foster a sense of belonging and community.

Suggestions

We are probably all guilty of complaining about students that

are not ‘doing their homework’, ‘working hard enough’, or ‘attending

class regularly’. As previously stated, there are a multitude of reasons

for these behaviours, but socio-cultural factors may be affecting some

students more than others. Talk to the student and find out why they

were online all night: was it to decrease loneliness? In situations

where socio-cultural adjustment is particularly difficult, I have found

that directing students to college counsellors, bringing them to the

International Office and introducing them to staff and students, and

sending them links to campus cultural clubs can assist in their

transition by fostering community membership, meeting potential

advocates, and talking to those who have ‘survived’ the transition for

advice and empathy. We are not trained to assist with these issues; we

are teachers, but we can guide them to those who can.

Conclusion

International students are not just negotiating academic needs;

they are concurrently navigating basic, safety and belonging needs

socio-culturally. Sometimes, physiological issues and safety needs or

concerns will manifest as a lack of concentration in class. Homework may

not be done because of hours on the internet researching health

information or Skyping with family to diminish loneliness. The lives of

international students, especially at the beginning, are complex. We

need to be aware that there are many possible, but invisible, causes to

ineffective classroom behaviours and not make assumptions. My students

need EAP, but sometimes life will be more pressing than the ten academic

words I assigned for homework. “Education that ignores the conditions

of students’ lives and simply focuses on transferring knowledge denies

students their humanity” (Benesch, 2001, p.52).

References

Benesch, S. (2001). Critical English for academic purposes:

theory, politics, and practice. Mahwah, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum.

Brinton, D.,M., Snow, M.,A., & Wesche, M. (2003). Content-based Second language Instruction (Classics

Ed.) MI: University of Michigan Press.

Bruce, I. (2011). Theory and concepts of English for Academic Purposes. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). New themes and approaches in second

language motivation research. Annual Review of Applied

Linguistics, 21, 43-59

Gregerson, T. & Horwitz, E.K. (2002). Language learning

and perfectionism: Anxious and non-anxious language learners’

reactions to their own oral performance. The Modern Language

Journal, 68 (iv), 562-570.

Horwitz, E.K. (2001). Language anxiety and achievement. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 21, 112-126.

Hyland, K. (2006). English for Academic Purposes. New York, NY: Routledge

Owens, A.R., & Loomes, S.L. (2010). Managing and

resourcing a program of social integration initiatives for

international university students: What are the benefits? Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 32 (3), 275-290.

Sparks, R.L., & Ganschow, L. (1991). Foreign language

learning differences: Affective or native language aptitude

differences? The Modern Language Journal, 75 (i),

3-16.

Sparks, R.L., & Ganschow, L. (1995). A strong inference

approach to causal factors in foreign language learning: A response to

MacIntyre. The Modern Language Journal, 79 (ii),

235- 244.

Angela teaches EAP at Fanshawe College in London,

Ontario and is a Doctoral student in Applied Linguistics at York

University in Toronto. Her research and teaching interests include EAP,

reading comprehension, academic writing, and teacher education. |