|

Despite many important advances in our field over the years,

intercultural concerns remain primarily within special interest groups. A

more effective response to these concerns, however, must involve our

collective efforts. As Sercu (2006) proposed, we may need to broaden our

professional identity. For this to happen, however, we need to

reexamine our goal and our role as language educators.

If our goal is to prepare students for effective, appropriate,

and positive intercultural participation through effective

communication, our students need not only to make themselves understood

but also to gain acceptance behaviorally and interactionally, especially

because acceptance by others is more often strained by offending

behaviors than by incorrect grammar. This insight, in fact, prompted the

development of the field of intercultural communication more than 50

years ago. In today’s world, we need to rethink the design and

implementation of language courses, given their potential to affect

millions of people worldwide.

Curiously, intercultural educators who explore perceptions,

behaviors, and interactional strategies mostly ignore the specific

language of encounters. And conversely, language teachers generally

overlook behavioral and interactional aspects; after all, we call

ourselves language teachers, not teachers of intercultural competence.

Yet the latter is precisely what is needed to produce competent English

language learners.

Intercultural abilities have been identified by a great many

names: global competence, transcultural communication, and global intelligence, among others. No

clear consensus exists among interculturalists about the terms or their

meanings. An extensive survey of the literature (over 240 publications),

however, substantiates intercultural (communicative)

competence (ICC) as the most widely used and most

comprehensive term.

It is clear that ICC involves a complex of abilities that are

necessary to perform effectively and appropriately when interacting with

others who are linguistically and culturally different from oneself.

Whereas effective reflects a view of one’s own

performance in the target language-culture (LC2; i.e., an etic or outsider’s view), appropriate reflects

how native speakers perceive such performance (i.e., an emic or insider’s view). Our task, then, as ESOL educators is to

help students recognize their etic stance while attempting to uncover

the emic viewpoint. The aim is not necessarily that students will

achieve native-like fluency, but that they will develop some degree of

ability in communicating and interacting in the style of LC2

interlocutors.

On the basis of the results of the literature survey, I

proposed a construct of ICC with multiple and interrelated components,

as follows (described in more detail below): a cluster of

characteristics, three areas, four dimensions, target language

proficiency, and developmental levels. Not all of these components,

however, are equally promoted through classroom work alone; direct

experience with the LC2 greatly enhances their development. This

observation led the Consortium for North American Higher Education

Collaboration and the American Council on International Intercultural

Education to strongly endorse academic mobility and other intercultural

experiences for all college students.

Nonetheless, ESOL classes initiate processes that often lead to

intercultural experiences, and ESOL classes provide venues where

students can process their experiences that occur outside the classroom.

Both situations assume, of course, appropriate course designs and

strategies.

Characteristics of ICC most commonly cited in the literature

are flexibility, humor, patience, openness, interest, curiosity,

empathy, tolerance for ambiguity, and suspending judgments, among

others. The three interrelated ICC areas are the ability to establish

and maintain relationships, the ability to communicate with minimal loss

or distortion, and the ability to cooperate to accomplish tasks of

mutual interest or need. Each area is embedded within the others; no one

area alone is adequate for ICC.

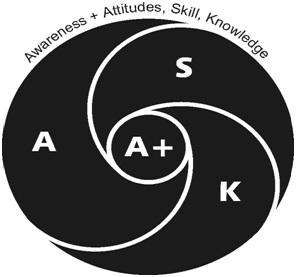

Consider also the four dimensions of ICC: knowledge, (positive)

attitudes (or affect), skills, and awareness (shown in the KASA

Paradigm; see Figure 1). All four allude to both target culture (LC2)

and one’s native culture (LC1); this is especially true of awareness

placed at the center. Awareness is enhanced through reflection and

introspection by comparing and contrasting the LC1 and the LC2. It

differs from knowledge, focusing on the self vis-à-vis everything else

in the world—things, people, thoughts—and ultimately elucidates what is

most relevant to one’s values and identity. Whereas knowledge can be

forgotten, awareness is irreversible.

Figure 1. The KASA Paradigm

Language proficiency is central to ICC (although not equal to

it) and, of course, central to our task as ESOL educators. Communicative

ability in the target language enhances all other ICC aspects in

quantitative and qualitative ways: Grappling with another language

causes people to confront how they perceive, conceptualize, and express

themselves, and it promotes new communication strategies on someone

else’s terms. This challenge aids in transcending and transforming one’s

habitual view of the world. Conversely, lack of a second language, even

minimally, constrains people to think about the world and act within it

only in their native system. Lack of a second language, then, deprives

people of a valuable aspect of intercultural experience (suggesting why

ESOL teachers must also be students of another tongue).

IMPLEMENTING CULTURAL AND INTERCULTURAL EXPLORATION

Both ESL and EFL contexts present different possibilities for cultural exploration. In the ESL

context, learners are immersed in an English-speaking milieu and

classroom work is naturally bolstered by continuing exposure to English,

even after classes are over. In the EFL context, however, English is

often limited to the classroom itself, with fewer opportunities for

real-life exposure. Nonetheless, in both situations cultural and

cross-cultural exploration is essential for furthering students’

development of intercultural competence.

The Process Approach Framework (A. E. Fantini, 1999) can help

to ensure the inclusion of cultural and cross-cultural activities in the

classroom. This framework posits seven stages to guide lesson plan

development:

- Presentation of new material

- Practice in context

- Grammar exploration

- Transposition (or use)

- Sociolinguistic exploration

- Target culture exploration

- Intercultural exploration

Whereas most teachers are familiar with stages 1 through 4, the

latter stages are less common. But including these three additional

stages ensures that language exploration is complemented by explicit

attention to sociolinguistic, cultural, and intercultural aspects.

Textbooks generally focus on language structure and, increasingly,

communication (stages 1 through 4) but pay little attention to stages 5

through 7, and teachers must often develop such activities on their own

(or not).

This framework establishes an explicit process that clarifies

objectives and activities that are appropriate for each of the seven

stages of a lesson unit. It also helps teachers select, sequence, and

evaluate learning and teaching activities that are chosen because of

their match with learning objectives. Most important, when developing

the course syllabus and lesson plans, teachers are reminded that stages 5

through 7 activities form part of each lesson cycle. Of course, not all

stages need to be covered in a single lesson; rather, together they

form a unit of material in which the cycle from stages 1 through 7 is

completed before going on to present new material. In the end, what

remains important is that language, cultural, and cross-cultural

exploration together form the integral parts of each unit and together

enhance the development of intercultural competence.

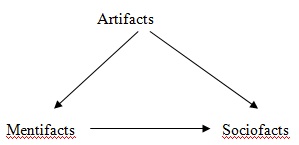

A second framework that aids in cultural and cross-cultural

exploration addresses relationships among artifacts, sociofacts, and

mentifacts (ASM; B. Fantini & Fantini, 1997), a model adopted by

the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages as part of

the National Standards for Foreign Languages (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The ASM Framework

Based on a sociological concept, this framework interrelates

three cultural dimensions: artifacts (things people make), sociofacts

(how people come together and for what purpose), and mentifacts (what

people think or believe). This scheme reminds us that whatever dimension

one begins with, the other two are also present and available, and

their exploration helps deepen understanding of the target

language–culture paradigm.

For example, if we consider any object or item (say, a

sandwich), we can investigate, first of all, what a sandwich is (e.g.,

lunch, snack, bread and cold cuts); then what types of people use a

sandwich, and how (e.g., working people, students, for picnics, bite

size to accompany cocktails); and finally, what the notion of sandwich

represents or means (e.g., portable, inexpensive, quick, common fare).

This exploration goes beyond merely considering cultural items; it

encourages the consideration of their social uses and significance. In

addition, comparing the artifacts, sociofacts, and mentifacts of host

culture items with those of the learners’ cultures (e.g., sandwiches

with tacos or rice balls) permits cross-cultural

investigation.

Many varied, interesting, and exciting activities exist to help

address the cultural and cross-cultural aspects of language. Some have

been developed within the intercultural field yet fit nicely into stages

5 through 7. For example, New Ways in Teaching

Culture (A. E. Fantini, 1997) contains 50 activities selected

from submissions sent by educators from around the world and grouped

according to their focus on sociolinguistic, cultural, or intercultural

exploration.

Of the many possibilities, I will describe one class of

techniques—operations—that are essentially ordinary activities from

everyday life that reveal cultural information. One example is how to

prepare a peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwich, something that every young

(and even older) American is familiar with.

Have students sit in a semicircle so that they can all witness

the operation and provide some background or context for the event.

Then, using real props, make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich,

explaining the process one step at the time. After completing the

operation, ask students to recount what they experienced and to narrate

the precise steps in sequence. Then have the class give instructions to a

volunteer for making a second sandwich. When the task is completed,

students can taste small pieces of the sandwich and comment on their

reactions. Cross-cultural exploration can be accomplished by then having

students discuss comparable snacks in their own cultures. Innumerable

operations and variations are possible as follow-up

activities.

CONCLUSION

Helping students develop intercultural competence is not only

fun but essential. Frameworks such as the Process Approach and the ASM

models can help teachers develop lesson plans that include activities

that explore cultural and cross-cultural aspects of English. These

activities add new dimensions to the traditional language class while

helping students develop the knowledge, attitude, skills, and awareness

that will foster development of the competence they need for

English-speaking contexts.

Developing ICC is clearly a challenge—for educators and

learners alike—but its attainment makes room for exciting possibilities.

It offers a chance to transcend the limitations of one’s own worldview.

“If you want to know about water,” it has been said, “don’t ask a

goldfish.” Intercultural contact is a provocative educational experience

precisely because it permits people to learn about others and

themselves. On the other hand, a lack of ICC can result in negative

outcomes such as the misunderstandings, conflict, ethnic strife, and

genocide that result from failed interactions across cultures.

Today, everyone needs ICC, and we as language educators play a

major role in this effort. Achieving this, however, requires a paradigm

shift—and an expansion of our professional vision.

REFERENCES

Fantini, A. E. (Ed.). (1997). New ways in teaching culture. Alexandria, VA: TESOL.

Fantini, A. E. (1999). Comparisons: Towards the development of

intercultural competence. In J. K. Phillips (Ed.), Foreign

language standards (pp. 165–218). Lincolnwood, IL: National

Textbook Company.

Fantini, B., & Fantini, A. E. (1997). Artifacts,

sociofacts, mentifacts: A sociocultural framework. In A. E. Fantini

(Ed.), New ways in teaching culture (pp. 57–61).

Alexandria, VA: TESOL.

Sercu, L. (2006). The foreign language and intercultural

competence teacher: The acquisition of a new professional identity. Intercultural Education, 17, 55–72.

Dr. Alvino E. Fantiniholds degrees in anthropology and

applied linguistics and has worked in language education and

intercultural communication for over 40 years. His research has produced

publications in bilingualism, language development, and language and

cross-cultural matters, including Language Acquisition of a

Bilingual Child and TESOL’s New Ways in Teaching

Culture. Fantini served on the National Advisory Panel, which

developed the National Foreign Language Standards for U.S. education. He

is past president of SIETAR International, a recent graduate faculty

member of Matsuyama University, Japan, and professor emeritus at the SIT

Graduate Institute in Vermont, and is currently serving as an

international consultant. |