|

Writing center tutoring consists of a variety of speech acts,

including suggestions. The results of the study discussed in this

article show that different factors may affect the use of various

suggestion linguistic realization strategies at face-to face writing

center sessions, including the influence of a person’s first language,

home country culture and level of L2 proficiency, social distance, power

and imposition, and other social and psychological factors. All of

these factors should be considered when training writing center tutors

so that they can use different and appropriate forms of providing

suggestions.

Performing speech acts has been regarded as a complex

phenomenon that intrinsically involves interaction between at least two

participants (Jiang, 2006; Koester, 2002). For example, suggestions are

the acts in which the speaker asks the hearer to perform an action that

will potentially benefit the hearer (Rintell, 1979). They belong to the

group of directive speech acts which, according to Searle (1976), are

those in which the speaker’s purpose is to get the hearer to commit

him/herself to some future course of action.

Studies (e.g., Bardovi-Harlig, 1999; Kuriscak, 2010) suggest

that not all speakers in their native language (L1) produce and respond

to suggestions and other speech acts in the same way. Second language

(L2) learners also show much variation in how they perceive and carry

out their own or react to others’ speech acts. As demonstrated in many

studies (e.g., Bardovi-Harlig, 2001; Félix-Brasdefer, 2003; Matsumura,

2003; Owen, 2002; Taguchi, 2007), linguistic competence does not

necessarily correlate with pragmatic competence. At some point in my

work as a writing center tutor, this made me assume that various

factors, including location of the interaction, age and social status of

the interlocutor, the level of familiarity with the interlocutor and

the culture of the interlocutor’s home country as well as various

personality measures, study abroad experience, motivation, and L2

proficiency level should influence L2 speakers’ production and reaction

to others’ speech acts, including suggestions. This also gradually made

me realize that using different strategies of providing suggestions in

accordance with the specific features of a particular communicative

situation is one way to ensure effective communication between tutors

and students at face-to-face writing center consultations.

Writing centers can be regarded as an example of such a place

where the aforementioned factors interact with each other, and where

they determine students’ pragmatic and writing development in a certain

language. Writing centers aim to help students improve their writing

through individualized assistance. However, successful study depends on

good communication between tutors and student writers (Fujioka, 2012).

Fujioka (2012) concludes that pragmatics can play a key role in

effective communication in writing center practice that studying writing

center tutoring sessions, with their rich language interactions and

opportunities as a learning place for both tutors and student writers,

can enhance our understanding of human interaction and development from

both applied linguistics and educational perspectives. Thus, when

writing center tutoring is conducted in students’ L1s and especially in

students’ L2s, it is important that tutors attend to pragmatic elements

that affect tutoring talk and help students communicate smoothly in the

tutoring session.

Writing center tutoring consists of a variety of speech acts.

Tutors compliment students’ writing, request information about the

content and purposes of writing, and offer suggestions for improvement,

while students coming to writing centers may request tutors to repeat

utterances as well as accept or reject tutors’ suggestions (Fujioka,

2012). The proper use of these speech acts depends on one’s knowledge

and understanding of communication norms and traditions associated with

L2 interactions. At the same time, as it was shown earlier, another

pragmatic aspect implying the existence of different social norms and

cultural values is associated with suggestions in a variety of

languages. Providing and interpreting suggestions expressed by writing

center tutors and student writers in appropriate ways is one of the

prerequisites ensuring effective communication between tutors and

students at the consultations organized by writing centers.

The importance of understanding different peculiarities of

using various suggestion linguistic realization strategies (SLRS)—that

is, pragmalinguistic forms of providing suggestions (e.g.,

Martínez-Flor, 2010; Wolfson, 1983)—for avoiding miscommunication

between tutors and L1 or L2 writer students explains the necessity of

investigating forms of suggestions used by writing center tutors and

their clients in different communicative situations which may take place

in writing center practice. Therefore, this study examines and presents

various similarities and differences observed in the ways of using

different SLRS at the writing center sessions conducted by the tutors

being the native or nonnative speakers of English for the students who

are also the native or nonnative speakers of English.

The corpus consisted of 17 transcripts of the consultations at

the writing center of one of the U.S. universities located in the

south-central part of the country. All those consultations were

videotaped in 2014 for investigating the intonation units observed in

the speech of tutors and clients. Each consultation lasted 45–65 minutes

(mostly 50–55 minutes). Twenty-seven subjects (10 tutors and 17

students) were involved in this study, including six native-speaking

(NS) and four nonnative-speaking (NNS) tutors (both male and female) as

well as nine NS and eight NNS students (both male and female too). All

sessions analyzed in this study were divided into four major groups: 1)

the sessions conducted by NS tutors for NS students, 2) the sessions

organized by NS tutors for NNS students, 3) the sessions conducted by

NNS tutors for NS students, and 4) the sessions by NNS tutors for NNS

students.

In the process of research, a transcription of writing center

consultations retaining the phonological images of words and

sociolinguistically relevant information was used. All features of

natural speech (including word repetitions, use of interjections and

pause-fillers, occurrences of stumbling, etc.) were reflected in the

transcription and preserved in the examples cited in this article. After

transcribing all 17 sessions analyzed in this study, the occurrences of

suggestions provided at those sessions were identified and categorized

into the groups and subgroups included in Martínez-Flor’s (2005)

classification of different kinds of SLRS (see Table 1).

Table 1. Taxonomy of Suggestion Linguistic Realization Strategies

(from Martínez-Flor, 2005, p. 175)

|

Type |

Strategy |

Example |

|

DIRECT |

Performative verb

Noun of suggestion

Imperative

Negative imperative |

I suggest that you …

I advise you to …

I recommend that you …

My suggestion would be …

My suggestion would be …

Try using …

Don’t try to … |

|

CONVENTIONALISED FORMS |

Specific formulae

(interrogative forms)

Possibility/probability

Obligation

Need

Conditional |

Why don’t you …?

How about …?

What about …?

Have you thought about …?

You can …

You could …

You may …

You might …

You should …

You have to…

You need …

If I were you, I would … |

|

Inclination |

I will …

I’ll …

I want to …

I would like to … |

|

INDIRECT |

Impersonal

Hints |

One thing (that you can do) would be …

Here’s one possibility: …

There are a number of options that you …

It would be helpful if you …

It might be better to …

A good idea would be …

It would be nice if …

I’ve heard that … |

As shown in Table 1, the first type of suggestions involves

that of direct strategies, in which speaker clearly states what he/she

means. Direct suggestions are performed by means of imperatives and

negative imperatives, a noun of suggestion, and performative verbs

(e.g., I suggest that you buy a new laptop). The type of

conventionalized forms for suggestions still allow the hearers to

understand the speaker’s intentions behind the suggestion, because the

illocutionary force indicator appears in the utterance, although this

second type of suggestion realisations is not as direct as the first

type. Within this group, there is a greater variety of linguistic

realisations to be employed, such as the use of specific formulae,

expressions of possibility or probability, suggestions performed by

means of the verbs should and need, and the use of the conditional (e.g., Have you

thought about buying a new computer?). This group of suggestions may

also include the expressions of inclination, or a particular disposition

of the speaker him/herself toward the things discussed with his/her

interlocutor(s) (e.g., I want to use in this phrase the preposition in rather than at as it is done in

the current variant of your writing). Finally, the group of indirect

suggestions refers to those expressions in which the speaker’s true

intentions are not clearly stated. These indirect forms for suggestions

do not show any conventionalized forms. That is, there is no indicator

of the suggestive force in the utterance, so the hearer has to infer

that the speaker is actually making a suggestion. The use of different

impersonal forms has been regarded as a way of making indirect

suggestions and the use of hints is considered the most indirect type of

comment that can be employed to make a suggestion (e.g., It would be

helpful if you bought a new computer; Martínez-Flor, 2010).

Understanding these differences between various forms of providing

suggestions should help writing center tutors ensure their effective

communication with clients and, eventually, the higher level of uptake

of tutors’ advice.

Beside systematizing all SLRS identified in this study into

different categories in accordance with Martínez-Flor’s (2005)

classification, this data set also includes information about the token

frequency of using different kinds of SLRS in all four groups of writing

center sessions analyzed in this project. It means that the percentage

data used in our analysis refer to the overall frequency of providing

suggestions in the transcripts of the study, including the instances of

the suggestions having the same structure and containing the same

lexical units. Calculating and comparing the token frequency of using

different kinds of SLRS in different kinds of writing center sessions

enabled me to determine what kinds of these strategies tend to prevail

in each of them, as well as to identify and interpret the trends

observed in the use of different forms of SLRS by NS and NNS writing

center tutors in their actual work with NS and NNS students.

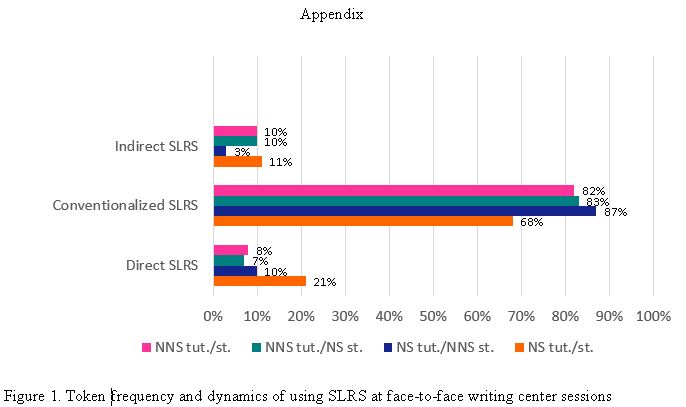

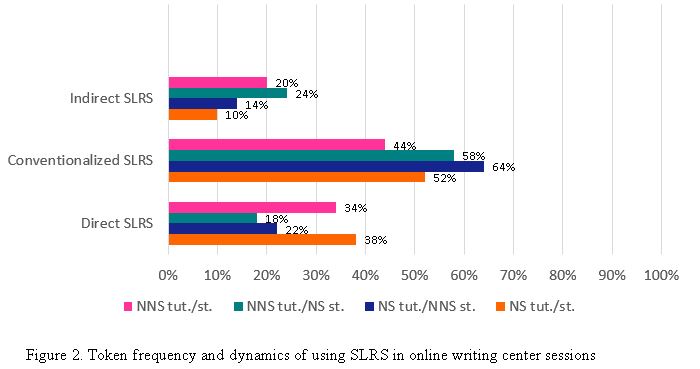

This study reveals that the use of suggestions in different

kinds of the writing center sessions analyzed in this study is

characterized by some common and varying features. Information about the

presence (“+”) or absence (“–“) of certain SLRS, which were revealed in

different groups of writing center consultations, is presented in Table

2. They also indicate the token frequency of using various SLRS in all

four groups of the sessions investigated in this study. Observations

regarding the use of direct suggestions in writing center practice are

summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Variety and Token Frequency of Using Direct SLRS at Writing Center Sessions

|

Type of Writing Center Session |

Direct/

Imperative |

Direct/

Negative

Imperative |

Direct/

Performative

Verb |

|

NS Tutors-NS Students |

+

(11%) |

+

(4%) |

+

(6%) |

|

NS Tutors-NNS Students |

+

(7%) |

– |

+

(3%) |

|

NNS Tutors-NS Students |

+

(5%) |

– |

+

(2%) |

|

NNS Tutors-NNS Students |

+

(8%) |

– |

– |

The results suggest that the widest range of direct SLRS was

observed in the transcripts of the sessions conducted by NS tutors for

NS students. In particular, while imperative forms of verbs and

performative verbs were used in all or almost in all kinds of writing

center sessions, the Negative Imperative strategy of providing

suggestions was observed only at the sessions conducted by NS tutors for

NS students, for example:

Tutor (T): Only because it could be Master’s

plural because more than one people, and then again it could be…But

even if, I mean, they are always called Master’s, so I’d like you wouldn’t say “my Master

degree.”

Student (S): Right.

In this example, the tutor preferred to use the direct negative

imperative form of providing suggestions (“I’d like you wouldn’t say…”)

to show the student what he/she (the tutor) wouldn’t like the student

to do. It is interesting that in this case (as well as in some examples

of using this strategy revealed in the transcripts), the imperative verb

form is mitigated with the help of the subjunctive construction “I’d

like you.” This probably makes the tutor’s suggestion not so categorical

and not so peremptory as it would sound without the use of this or any

other similar mitigation device.

It is quite possible that the Negative Imperative strategy was

employed at the sessions conducted by NS tutors for NS students because

of NS tutors’ wish to emphasize the importance of certain things while

being not afraid of becoming too strict or persistent in their work with

NS students. This tendency can also be explained by the fact that

English is the first language for all of those tutors and students.

Besides, as they have lived in the United States for at least most of

their lives, it is logical to assume that they are highly familiar with

the traditions of communication that are popular in the American

culture. Hence NS tutors’ and NS students’ expectations about each

other’s English proficiency and familiarity with the local traditions of

communication in different situations are quite high, which enables NS

tutors to use a variety of SLRS in their comments and remarks.

It also follows from the data presented in Table 2 that the NS

and NNS tutors working with NNS students tended to use the imperative

forms of verbs and performative forms of SLRS more often than the NS

tutors working with NS students and the NNS tutors working with NS

students:

T: This is the one, I mean, your other career

goal… Ja, it’s what I would

suggest.

S: Okay.

In this case, the tutor showed explicitly that his/her advice

about making certain grammar changes in the student’s writing was based

on his/her own experience and on his/her own assumptions. At the same

time, the use of the performative verb to suggest made the tutor’s suggestion more noticeable and persuasive

(even if it was mitigated with the help of would).

Perhaps a more frequent use of the imperative forms of verbs

and performative forms of SLRS in tutors’ work with NNS students is

connected with tutors’ wish or necessity to simplify their language when

communicating with NNS students. In the case of NNS tutors, feeling

more “at the same social level” with NNS students rather than with NS

students may have stimulated them to become more directive in such

cases, too.

The results of the study suggest that the smallest range of

different kinds of direct suggestions was observed in the transcripts of

the sessions conducted by NNS tutors for NNS students. A more limited

number of different kinds of direct SLRS used in NNS tutors’ remarks

compared to those of NS tutors can be connected with the fact that,

unlike the NS tutors working at the university where this study was

conducted, the NNS writing center consultants working at that university

have lived in another country for at least most of their lives.

Therefore, they may be not very familiar with the local traditions of

communication and particularly with the pragmatic norms preferred in

American culture. Numerous studies (e.g., Bardovi-Harlig &

Hartford, 1990; Matsumura, 2001; Rintell, 1979) reveal that, because

English is not the L1 for NNS tutors and NNS students, some limitations

in the use of certain SLRS can also be connected with NNS tutors’ and

NNS students’ level of L2 proficiency, as well as with the actual level

of their familiarity with the local traditions of communication in

different situations.

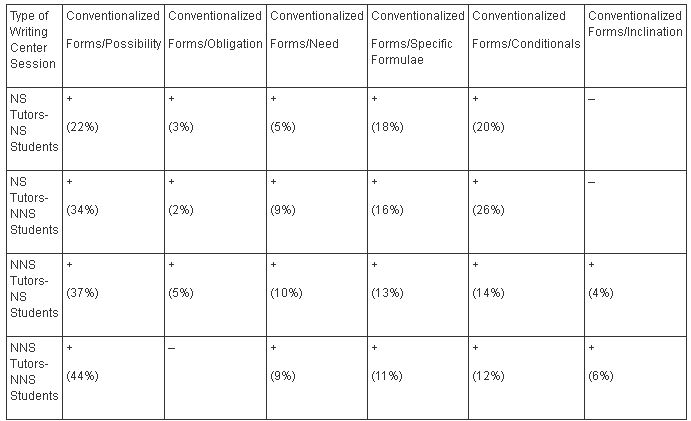

Some other tendencies reveal themselves in the use of different

conventionalized forms of providing SLRS at writing center sessions

(see Table 3).

Table 3. Variety and Token Frequency of Using Conventionalized

Forms of Providing SLRS at Writing Center Sessions (Click image to enlarge)

The data in Table 3 reveal that the majority of different kinds

of conventionalized forms of providing SLRS (including the

Possibility/Probability, Need, Specific Formulae, and Conditionals SLRS)

were used in all four groups of the sessions analyzed in this study,

for example:

T: …And then you can come to this quotation and to this conclusion…

S: Yeah, I think so.

In this example, the use of the second-person pronoun you and the modal verb can in the

tutor’s suggestion allowed the student to infer that the tutor expected

some reaction from him/her and that the student could either agree or

disagree with the tutor. This is likely why the student said “Yeah” in

his response to the tutor’s comment.

It is interesting that in most cases, the token frequency of

using different kinds of conventionalized forms of providing SLRS was

rather similar in different kinds of sessions, too. It is also worth

noting here that some conventionalized forms of providing SLRS (namely,

the Possibility/Probability, Specific Formulae, and Conditional forms)

prevailed over direct and indirect SLRS in all four groups of writing

center sessions. This tendency can be probably connected with the

popularity of these forms of providing suggestions in different

languages and cultures. Their frequent use by the NS and NNS tutors

working with NS and NNS students may also have been caused by the

tutors’ understanding of the rules of politeness and their experience of

communicating in different social situations.

Though most of the conventionalized formulae were identified in

all kinds of writing sessions, the Inclination form of providing

suggestions was observed only at the sessions organized by NNS tutors

(both for NS and NNS students), for instance:

T: Okay. I’ll just cross this off, then.

S: Okay, right.

As can be seen from this example, of all conventionalized forms

of providing SLRS, the Inclination suggestions are the most categorical

ones. It is possible that NNS tutors tended to use them in those

situations when they were confident in the validity of their

suggestions, and perhaps in those cases when their current level of

English proficiency did not let them use some other linguistic and

rhetorical means for making their utterances sound stronger and more

persuasive (e.g., certain evaluative and emotional lexical units,

idioms, emphatic constructions, rhetorical questions).

The Inclination form of providing suggestions was observed only at sessions by NNS tutors. This may be explained by the influence of NNS tutors’ home country culture, their previous teaching experiences in their home country, and their communicative behavior in the host country. Their tendency to

be more direct in general and some possible limitations caused by their

current level of L2 proficiency and familiarity with the local

traditions of communication in different situations could also be

regarded as the factors leading them to use the Inclination form of

providing suggestions in their writing center practice.

It is also important to mention here that, while the Obligation

form of providing SLRS was used at most of the sessions investigated in

this project, it was not found in the transcripts of the sessions

conducted by the NNS tutors working with NNS students. Perhaps the

absence of the Obligation form of SLRS in this group of writing center

sessions is connected with the wish of NNS tutors not to put too much

pressure on NNS students. Being not so confident about the validity of

some of their suggestions compared to NS tutors and feeling as if they

were at the same social level with NNS students rather than with NS

students may have influenced NNS tutors’ avoidance of employing the

Obligation form of SLRS in their work with NNS students, too. To some

extent, this resembles the results of Banerjee and Carrell’s (1988)

study, which showed that NNS are significantly less likely to make

suggestions in potentially embarrassing situations than NS. NS and NNS

tutors’ and students’ expectations about their actual knowledge of the

necessary pragmatic norms and about their previous experience of

communication in some similar situations could also play some role in

NNS tutors’ avoidance of using the Obligation form of providing SLRS in

certain situations. Perhaps this also explains why in their work with NS

and NNS students, NNS tutors tended to use a greater number of sentence

modifiers for mitigating their suggestions, compared to NS

tutors.

Finally, the findings related to the use of indirect SLRS at

the writing center sessions are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Variety and Token Frequency of Using Indirect SLRS at Writing Center Sessions

|

Type of Writing Center Session |

Hint |

Impersonal |

|

NS Tutors-NS Students |

+

(4%) |

+

(7%) |

|

NS Tutors-NNS Students |

+

(3%) |

– |

|

NNS Tutors-NS Students |

+

(6%) |

+

(4%) |

|

NNS Tutors-NNS Students |

+

(4%) |

+

(6%) |

As shown in Table 4, almost all groups of tutors and students

(except the NS tutor-NNS students’ group) applied both forms of indirect

strategies. Though the Impersonal form of SLRS was not used only by the

NS tutors working with NNS students, the Hint form of SLRS could be

observed in all four groups of the sessions analyzed in this study, for

example:

T: This theme of diversity forms the rhetoric of the speech. You use the word rhetoric a

lot.

S: Yeah, I know. Oratory, for example?

In this case, adding the hint “You use the word rhetoric a lot” stimulates the student to come up

with a synonym (oratory). Formulating his/her

suggestion in the form of a hint made the tutor’s comment less

categorical and more indirect at the same time.

As follows from the results of the analysis, the use of hints

and impersonal SLRS prevailed at the sessions of NNS tutors conducted

for NS students:

T: It’s also better to paraphrase this part, not just to repeat.

S: Okay.

The use of the impersonal pronoun it and the

absence of any first- or second-person pronouns and downgraders in this

suggestion made the latter sound more direct and didactic. So, it is

not surprising that the student just replies “Okay,” not showing any

attempt to add anything to the tutor’s suggestion or to express his/her

opinion about its usefulness in this particular case. In this

connection, it is possible to conclude that the ways of formulating

one’s suggestions and the choice of certain SLRS may either amplify or

minimize the threat to the hearer’s face and thus either increase or

reduce the impact that suggestions make on the interlocutor.

Prevalence of hints and impersonal SLRS at the sessions

organized by NNS tutors for NS students may be connected with a lower

degree of NNS tutors’ confidence in the effectiveness of their

suggestions in such cases, as well as with their willingness to share

the responsibility for the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of their

suggestions with the students themselves.

Based on the findings in previous research (e.g.,

Bardovi-Harlig & Hartford, 1990; House & Kasper, 1981;

Koike, 1994; Matsumura, 2003), it is possible to assume that the

aforementioned tendencies regarding the use of different kind of SLRS in

the four groups of writing center sessions analyzed in this study could

have been caused by different factors. First, the differences observed

in the ways of using various kinds of suggestions can be associated with

the influence of students’ L1s and the culture of their home country

culture as well as with the level of NNS tutors’ English language

proficiency at the time of conducting the study. The degree of their

familiarity with the local traditions of communication in different

social situations might have influenced their certain pragmatic choices

as well. Finally, some social factors, including the factors of social

distance, social power, and imposition, as well as the differences in

understanding of the principle of modesty peculiar to different

cultures, might have had much impact on choosing or not choosing this or

that strategy of providing suggestions by NS and NNS tutors working

with NS and NNS students.

The results also suggest that NS and NNS tutors’ suggestions

may occasionally consist of more than one move. In such cases, tutors’

remarks usually (but not always) include several different kinds of SLRS

which are combined together and which can be traced in one or two moves

comprising such a suggestion:

T: So…Yeah, let’s read on—I will say,

maybe…Could we put a mark in? This is what I

would suggest. Is that after this sentence? I’m ready to get

to your topic.

S: Okay.

In this fragment of the writing center session conducted by a

NS tutor for a NS student, the tutor used a specific conversational

formula (“let’s read on”), a question pointing to the fact of having the

possibility of undertaking a certain action (“Could we put a mark

in?”), and a performative verb (suggest in “This is

what I would suggest”). In this case, the tutor preferred to use several

forms of direct and conventionalized kinds of SLRS at the same time,

which should have increased the impact of his/her suggestions on the

student’s further actions and behavior regarding the student’s future

writing activities.

At the same time, occasionally the NS students working with NNS

tutors participated in coproducing suggestions with their tutors,

helping them express the necessary thoughts and ideas in

English:

T: En…So maybe consider…

S: …breaking the paragraph off from right here.

T: Right. Uh-huh.

In this fragment, the tutor began to express a suggestion (“So

maybe consider…”). As the tutor made a longer pause then (while,

probably, searching for appropriate English words and formulating

thoughts in English), the student continued formulating the tutor’s

suggestion, based on his/her own assumption about the idea which the

tutor might have planned to express in his/her suggestion. The tutor’s

reply (“Right”) points to the fact that the student’s guess regarding

the final part of the tutor’s suggestion was probably correct. It is

possible to say that in a few cases, NNS tutors and NS students were

coproducing suggestions. This tendency was not typical of the other

groups of writing center sessions analyzed in this study, which is

probably connected with the fact that during NNS tutors-NS students’

sessions, the NNS tutors for whom English is not the first language were

working with the NS students for whom English is the first language and

who therefore should have faced fewer difficulties when expressing the

necessary thoughts and ideas in English.

These observations reveal that the structure of suggestions and

the ways of providing them may highly vary in NS and NNS speakers’

utterances, depending on specific peculiarities of a certain

communicative situation, speakers’ motivation, their own and their

interlocutor’s social and cultural background, speakers’ L1 and the

level of their L2 proficiency, various psychological and social factors

(e.g., social distance, power, and imposition), as well as speakers’

understanding of the concept of politeness and the degree of their

familiarity with the pragmatic norms that are culturally accepted in the

culture where a concrete instance of communication takes place. A

combination of all these factors explains the complexity of pragmatic

variation which, as previously shown, could be observed in the use of

different kinds of SLRS by NS and NNS speakers in writing center

settings. Therefore, it is logical to conclude that all aforementioned

factors need to be considered in the system of training writing center

tutors so they can use and react to different forms of these and other

speech acts in appropriate ways. According to Wolfson (1989), the lack

of pragmatic competence can easily lead to a negative interpretation of

the interlocutor’s personal traits and stereotypes of other cultures. In

this connection, it is logical to assume that taking the aforementioned

factors into account can be helpful for writing center tutors in terms

of using various strategies of providing suggestions as effectively as

possible in the different communicative situations they may encounter

during face-to-face writing center sessions.

The findings in this study may also have some importance in

terms of planning the content and purposes of EFL/ESL, business English,

introduction into speech, and other classes connected with the

questions of language use and communication. Because suggestions reflect

certain values underlying different cultures, instruction regarding the

use of these speech acts can enhance students’ cultural literacy as

well as their linguistic control of these speech acts. Besides, as shown

by Martínez-Flor (2010), learners’ suggestions have often been regarded

as direct, unmitigated, and less polite than those made by NSs. In this

connection, numerous researchers (e.g., Koike & Pearson, 2005;

Martínez-Flor & Fukuya, 2005; Martínez-Flor & Alcón,

2007) suggest that some pedagogical intervention may be beneficial to

make learners become pragmatically competent when performing

suggestions. Through training and/or instruction, writing center tutors

and L2 learners can become better prepared for providing and

interpreting others’ suggestions as intended. In the long run, all this

should contribute to the enhancement of cross-cultural

understanding.

Click images to enlarge.

References

Banerjee, J., & Carrell, P. L. (1988). Tuck in your

shirt, you squid: Suggestions in ESL. Language Learning,

38(3), 313-364.

Bardovi-Harlig, K. (1999). Exploring the interlanguage of

interlanguage pragmatics: A research agenda for acquisitional

pragmatics. Language Learning, 49(4), 677-713. doi:

10.1111/0023-8333.00105

Bardovi-Harlig, K. (2001). Evaluating the empirical evidence:

Grounds for instruction in pragmatics? InK. K. Rose & G. Kasper

(Eds.), Pragmatics in Language Teaching (pp. 13-32).

Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Bardovi-Harlig, K., & Hartford, B. S. (1990).

Congruence in native and non-native conversations: Status balance in the

academic advising session. Language Learning, 40(4),

467-501.

Félix-Brasdefer, J. C. (2003). Declining an invitation: A

cross-cultural study of pragmatic strategies in American English and

Latin American Spanish. Multilingua, 22(3),

225-255.

Fujioka, M. (2012). Pragmatics in writing center tutoring:

Theory and suggestions for tutoring practice. Kinki University

Center for Liberal Arts and Foreign Language Education

Journal, 3(1), 129-146.

House, J., & Kasper, G. (1981). Politeness markers in

English and German. In F. Coulmas (Ed.), Conversational

Routine (pp. 157-185). The Hague, The Netherlands:

Mouton.

Jiang, X. (2006). Suggestions: What should ESL students know? System, 34(1), 36-54.

Koester, A. J. (2002). The performance of speech acts in

workplace conversations and the teaching of communicative functions. System, 30(2), 167-184.

Koike, D. A. (1994). Negation in Spanish and English

suggestions and requests: Mitigating effects? Journal of

Pragmatics, 21(5), 513-526.

Koike, D. A. & Pearson, L. (2005). The effect of

instruction and feedback in the development of pragmatic competence. System, 33(3), 481-501.

Kuriscak, L. M. (2010). The effect of individual-level

variables on speech act performance. In A. Martinez-Flor & E.

Usó-Juan (Eds.), Speech act performance: Theoretical, empirical

and methodological issues (pp. 23-39). Amsterdam, The

Netherlands /Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins Publishing

Company.

Martínez-Flor, A. (2005). A theoretical review of the speech

act of suggesting: Towards a taxonomy for its use in FLT. Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses, 18,

167-187.

Martínez-Flor, A. (2010). Suggestions. How social norms affect

pragmatic behavior. In A. Martinez-Flor & E. Usó-Juan (Eds.), Speech act performance: Theoretical, empirical and

methodological Issues (pp. 257-274). Amsterdam, The

Netherlands/Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins Publishing

Company.

Martínez-Flor, A. & Alcón, E. (2007). Developing

pragmatic awareness of suggestions in the EFL classroom: A focus on

instructional effects. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics,

(10)1, 47-76.

Martínez-Flor, A. & Fukuya, Y. I. (2005). The effects

of instruction on learners’ production of appropriate and accurate

suggestions. System, 33(3), 463-480.

Matsumura, S. (2001). Learning the rules for offering advice: A

quantitative approach to second language socialization. Language Learning, (51)4, 635-679.

Matsumura, S. (2003). Modelling the relationships among

interlanguage pragmatic development, L2 proficiency, and exposure to L2. Applied Linguistics, 24(4), 465-491.

Owen, J. S. (2002). Interlanguage pragmatics in

Russian: A study of the effects of study abroad and proficiency levels

on request strategies. Ph.D. dissertation, Bryn Mawr College,

PA.

Rintell, E. (1979). Getting your speech act together: The

pragmatic ability of second language learners. Working Papers

on Bilingualism, 17, 97-106.

Searle, J. (1976). A classification of illocutionary acts. Language in Society, 5(1), 1–23.

Taguchi, N. (2007). Task difficulty in oral speech act

production. Applied Linguistics, 28(1),

113-135.

Wolfson, N. (1983). An empirically-based analysis of

complimenting in American English. In N. Wolfson & E. Judd

(Eds.), Sociolinguistics and Language Acquisition

(pp. 82-95). Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Wolfson, N. (1989). Perspectives: Sociolinguistics and TESOL. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Olga Muranova

is currently a fifth-year PhD student majoring in TESOL/applied

linguistics and a graduate teaching/research associate in the English

Department at Oklahoma State University. Her research interests include

text linguistics (especially the linguistic and rhetorical features of

popular science texts), discourse and genre analysis, stylistics,

intercultural bilingualism, English for specific purposes teaching, and

teaching ESL/EFL writing. |