|

Aspired to popularize English so that it is “no longer linked

to a single culture or nation” (McKay, 2002, p. 24), English as an

international language teachers are encouraged to expose learners to

different cultures, avoid privileging any native-speaking English

cultures, and expect students to develop multicultural perspectives

without feeling pressed to adjust their communicative behaviors to any

specific English-speaking cultural group. Such teaching practices, while

making English classrooms more democratic, are susceptible to

unfavorable side effects on the cultivation of the intended alternative

cultural perspectives. From the perspective of complex adaptive systems

(CAS), mere exposure to or discussion about cultural products and

practices is not sufficient for the emergence of target cultural

perspectives in our knowledge system. The study discussed in this

article aims to visualize the registration of alternative cultural

perspectives in a person’s knowledge system and draw implications for

avoiding the unfavorable side effects of teaching English as an

international language.

Complex Adaptive Systems and Their “Internal Models”

A CAS is a network of many “agents” acting in parallel to adapt

to all the other agents’ behaviors (Holland, 2014). Agents may be

neurons, organisms, minds, or any self-sustaining entity capable of

adapting to its environment. Agents are themselves complex adaptive

systems. The environment of each agent is actually an emergent

phenomenon resulting from its interactions with all other agents. This

is why the context of communication is constantly changing (McDermott,

1976; Erickson, 2004). Agents are acting in parallel, so the system

assumes no center of control. This is why one’s goal-oriented action can

bring about side effects and why pure free will may not exist

(Gazzaniga, 2011; Eagleman, 2015). CAS are emergent and self-organizing.

New orders emerge as the agents’ interactions in novel circumstances

give rise to new patterns that push the original system away from

equilibrium (Kauffman, 1993). Newly emerged orders constitute a new

species of agents, whose interactions give rise to further novel

patterns and add other new species to the system. The constantly

emerging diversities constitute the transformation of CAS over time.

Active engagement in the process of transformation is crucial for CAS to

survive and thrive. The emergent nature of CAS determines that

higher-order thinking, such as cultural perspectives, may only emerge

when people act beyond their initial patterns. Therefore, understanding

how CAS learn and adapt will shed light on how cultural perspectives get

registered in the learner’s knowledge system.

CAS learn from experience. According to John Holland, one of

the founding fathers of complexity science, “All complex adaptive

systems … build models that allow them to anticipate the world”

(Waldrop, 1992, p. 177). The building blocks are the behavior patterns

that worked well in previous experiences. Each concrete experience, or

interaction, is registered in the agents as tacit “if [circumstances and

action]/then [outcome]” hypotheses, which accumulate into an “internal

model” (Holland, 1995, p. 57). The structure of the internal model is

thus determined by the agent’s unique internal structure and the

environment’s feedback concerning its action. Each internal model

“informs the agent of previous outcomes of particular actions in

particular circumstances and the likely outcomes of similar actions in

similar circumstances” (Wilson, 2017, para. 15). At a very large scale, a

cultural perspective is an integral internal model to a human society.

Each social interaction is a fraction of the entire model, so it has the

same level of detail as the entire model. If all

details are not oriented toward the target cultural perspective through

consistent feedback, the target cultural perspective may not get

registered in the learner’s knowledge system. This will be illustrated

with visual aids in a later section. The concept of internal model has

been understood in a variety of different terms, such as “script”

(Schank, 1990; Turner, 1991), “schema” (Rumelhart, 1980), and “proto

story” (Becker, 1995). However, I will keep the term “internal model” to

retain its broadest, systemic sense.

Cultural Perspectives as “Internal Models”

An understanding of how internal models emerge and change will

help us understand how cultural perspectives emerge and evolve as one

learns a language. Though internal models are too complex and dynamic to

be modeled, a visual representation of the human knowledge system (HKS)

will help us begin to conceptualize its complexity and interaction with

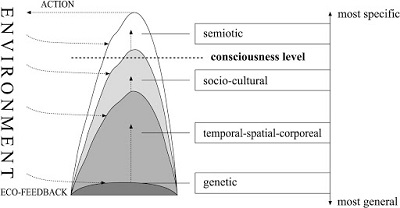

environment. Figure 1 is a rough representation of an HKS. The

representation has been inspired by Bateson’s (1972; 1979)

ecology-of-mind theory, Maturana and Varela’s (1992) autopoiesis theory, Nikolić’s (2014) practopoiesis theory, Donald’s (1991) hypothesis of

the three-stage evolution of the modern mind, Tomasello’s (2014)

hypothesis of the three-stage development of human thinking, and

Damasio’s (1999) philosophical account of different levels of

consciousness. The four major species of agents represented in Figure 1

include (1) genetic knowledge (which emerged as the genes interacted

with the environment), (2) temporal-spatial-corporeal knowledge (which

emerged as the body interacted with the environment), (3) sociocultural

knowledge (which emerged as the person interacted with the humanized

environment), and (4) semiotic knowledge (which emerged as the person

interacted with the shared symbolic systems). Each species is a fraction

of a different but interdependent larger system and co-evolves with the

larger system. For example, as the individual adjusts his behaviors in

response to other agents’ actions, his adjustment also contributes to

the evolution of language and culture on a larger scale over time.

Figure 1. Representation of human knowledge system.

The Environment in Figure 1 is emergent and specific to

individual agents. It is not separate from the agent. Each agent

interacts directly with its environment. The hierarchical structure

indicates the relative generalizability of the “if/then” hypotheses

registered in each species. The hypotheses in the same species also

display a similar hierarchy in terms of generalizability across the

larger system. For example, the reading of some gestures or facial

expressions are almost universal, whereas most sound patterns and

written symbols are unique to small groups of people. The more general

the hypotheses, the deeper they sink below consciousness and the less

frequently they change, but the more readily the relevant ones are

singled out for the given circumstance. This is why our body movements

and our perception of social contexts are mostly subconscious and

automatic. The upward arrows represent how one species’ emergence and

action are dependent on the existence of the species below it (which

have emerged earlier in learning and now act more automatically).

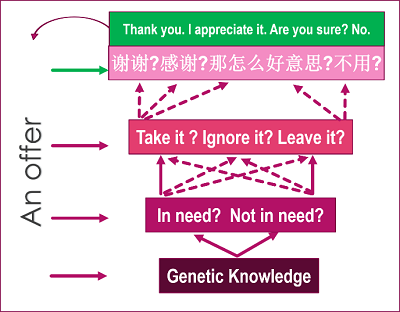

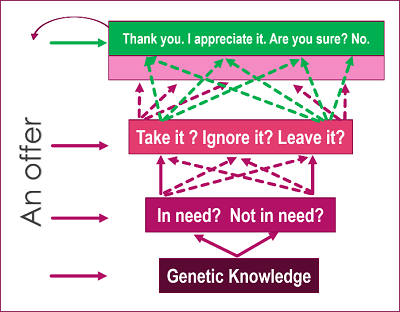

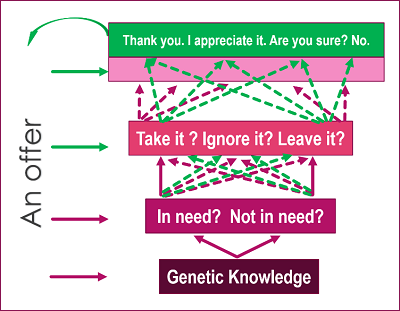

We can apply the representation of HKS to visualizing the

potential modifications to the internal model of a Chinese L1 learner’s

system, depending on the English L2 teacher’s feedback style. Figures 2,

3, and 4 represent the eventual effects of accuracy-oriented feedback

(Figure 2), fluency-oriented feedback (Figure 3), and context-oriented

feedback (Figure 4). All three representations assume the class is

communicative and the teacher employs elicitation strategies to allow

students to anticipate her action (i.e., an offer). In each figure, the

arrows indicate the alternative hypotheses that may be useful when an

offer is anticipated. The dotted arrows indicate the hypotheses

registered in the sociocultural agents. The purple colors indicate the

patterns emerged from L1 interactions, whereas the green color indicates

the patterns emerge from L2 interactions. Since adaptation is

conservative (Maturana & Varela, 1992), in any given

circumstance, the system will first test the hypothesis that requires

the minimum structural change of the system. If the action brings about

the anticipated outcome, the hypothesis will be considered viable and

used again in similar circumstances.

Figure 2. Accuracy-oriented models.

Figure 3. Fluency-oriented models.

Figure 4. Context-oriented models.

To respond to an offer in L2, the least costly action for the

system is to find an L2 “equivalent” for what one would say in L1, such

as “Thanks” for the Chinese word “谢谢xièxie” in the case of accepting. If

the only condition for positive feedback is accurate production of the

phrase “Thanks”, the modifications to the existing internal models

(Figure 2) will only involve the semiotic agents, namely “if accept an

offer and ‘Thanks’ instead of ‘Xiexie’, then positive feedback.” With

such models students may either appear retarded or be unintelligible in

spontaneous L2 communication due to the lack of “equivalents” between

cultures. To improve the situation, students may repeatedly perform the

speech act till the phrase “Thanks” becomes activated simultaneously

with the action of accepting. The modification (Figure 3) will then

involve the semiotic and the temporal-spatial-corporeal agents, namely

“if accept an offer and accompany the accepting movement with ‘Thanks’,

then positive feedback.” With such models students may become more

fluent in L2, but not more intelligent or likeable to L2 speakers who

are not familiar with their L1 culture because the judgement as to

whether it is appropriate to take the offer is still made from their L1

perspective. Different societies have different criteria for

culturally-appropriate behaviors (Agar, 1994) and verbalize different

aspects of events (Slobin, 1996).

For the student to automatically recognize social contexts from

an L2 perspective in spontaneous communication, modifications to

internal models must involve the sociocultural agents (Figure 4). For

the sociocultural agents to register useful hypotheses, the social

context of the offer (including the relationship between the people

involved and the content of the offer) must be specified and the teacher

must give negative feedback and model expected actions in the given

situation. The social context contains the basic elements of any

interpersonal interaction, so it is often taken for granted until the

action fails to bring about the anticipated outcome. This is why the

teacher’s consistent context-oriented feedback is crucial for the

emergence of alternative internal models in the learner’s system. For

example, since the Chinese counterpart for “Thanks” is only expected

when one accepts the offer, Chinese L1 learners tend to decline offers

by just saying “No”, whose Chinese counterpart “Búyòng” would suffice

for declining offers in Chinese-speaking contexts. Therefore, in L2

roleplaying, if a student tends to decline offers by just saying “No”,

it is necessary to always remind him to also say “Thanks” and have them

redo the act in the expected manner. The teacher may also have the

student enact situations where it is appropriate to decline offers by

just saying “No” without “Thanks”. For example, if on a cold day my

friend makes an offer by saying “Shall I close the door?” I may simply

say “No. I’m fine” to decline it. By contrast, if the offer is “Shall I

close the door for you?” or “Shall I get you a blanket?” then it would

be more appropriate to decline it by saying “No. I’m fine. Thank

you.”

Implications

Because consistent teacher

feedback concerning cultural behavior is key to the registration of

cultural perspectives, the target English culture(s) for any given class

should naturally be the one(s) of which the teacher can be

representative. The construction of alternative sociocultural models

would require the teacher to make explicit the specific context and

react to students’ behaviors in the ways a local of the target community

might act in the given context. Specific contextual information is

crucial for useful alternative sociocultural models to emerge. A basic

goal for cultural learning is to cultivate the awareness that

communication patterns are specific to particular groups, though some

patterns may be more generalizable than others. For this awareness to be

registered in the learner’s system, the teacher’s feedback must

consistently orient the learner’s communicative behaviors toward

specific cultures. With this awareness, learners will be more observant

and tolerant with cultural differences in cross-cultural communication.

Over time, this awareness will evolve into full-fledged alternative

cultural perspectives.

References

Agar, M. (1994). Language shock: Understanding the

culture of conversation. New York, NY: William Morrow and

Company.

Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind. New York, NY: Ballantine Books.

Bateson, G. (1979). Mind and nature: A necessary unity. New York, NY: E.P. Dutton.

Becker, A. L. (1995). Beyond translation: Essays

toward a modern philology. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of

Michigan Press.

Damasio, A. (1999). The feeling of what happens: Body

and emotion in the making of consciousness. New York, NY:

Harcourt Brace & Company.

Donald, M. (1991). Origins of the modern mind: Three

stages in the evolution of culture and cognition. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.

Eagleman, D. (2015). The brain with David Eagleman. [DVD]. United States: PBS.

Erickson, F. (2004). Talk and social theory: Ecologies

of speaking and listening in everyday life. Malden, MA:

Polity Press.

Gazzaniga, M. S. (2011). Who’s in charge? Free will

and the science of the brain. New York, NY:

HarperCollins.

Holland, J. H. (1995). Hidden order: How adaptation

builds complexity. New York, NY: Helix Books.

Holland, J. H. (2014). Complexity: A very short

introduction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Kauffman, S. (1993). Origins of order:

Self-organization and selection in evolution. New York, NY:

Oxford University Press.

Maturana, H. R., & Varela, F. J. (1992). The

tree of knowledge: The biological roots of human understanding

(R. Paolucci, Trans.). Boston, MA: Shambhala.

McDermott, R. P. (1976). Kids make sense: An

ethnographic account of the interactional management of success and

failure in one first grade classroom (Unpublished doctoral

dissertation), Stanford University, CA.

McKay, S. L. (2002). Teaching English as an

international language: Rethinking goals and perspectives. New

York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Masny, D., & Waterhouse, M. (2011). Mapping territories

and creating nomadic pathways with multiple literacies theory. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 27(3),

287–307.

Nikolić, D. (2014). Practopoieses: Or how life fosters a mind. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 373, 40–61. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2015.03.003

Rumelhart, D. E. (1980). Schemata: The building blocks of

cognition. In R. J. Spiro, B. C. Bruce, & W. F. Brewer (Eds.), Theoretical issues in reading comprehension (pp.

33–58). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Schank, R. C. (1990). Tell me a story: A new look at

real and artificial memory. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Slobin, D. (1996). From “thought and language” to “thinking for

speaking.” In J. J. Gumperz & S. C. Levinson (Eds.), Rethinking linguistic relativity (pp. 70–96).

Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Tomasello, M. (2014). A natural history of human

thinking. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Turner, M. (1991). Reading minds: The study of English

in the age of cognitive science. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press.

Waldrop, M. (1992). Complexity: The emerging science

at the edge of order and chaos. New York, NY: Simon and

Schuster.

Wilson, J. (2017). Learning, adaptation, and the complexity of

human and natural interactions in the ocean. Ecology and

Society, 22(2). Retrieved from

https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol22/iss2/art43/

Jianfen Wang, currently assistant professor of

Chinese at Berea College, taught EFL in China for seven years before she

received her MA in TESOL. In her PhD research toward a unitary account

of literacy development, she drew broadly from the natural and social

sciences. This allowed her to reflect critically on TESOL practices. |