|

Conversation Analysis (CA) consists of identifying and evaluating verbal and non-verbal interactions between two or more individuals. Markee (2000) determined that CA is a useful resource tool that can help second language acquisition researchers gain deeper insights and a variety of aspects about language teaching. Additionally, CA is a valuable type of assessment that can identify and determine speech impediments, varying types of spoken languages, and be an index for teachers who are seeking ways to help students learn and acquire the English language. Qi and Tian (2011) explained CA as a formative approach that can assist instructors with creating interactive speaking activities in the English a Foreign Language (EFL) classroom. Coincidentally happening in the comfort of a home, this article reveals implicit meaning-making that informs and incites reflection of one’s own coaching style.The informality of the conversation being conducted in one’s home reflected a “real-time talk” genre that created a relaxed and stress-free environment aimed to ease learning and problem-solving. The use of CA as a method and a rebus puzzle as a teaching tool captured significant nuances of intercultural communication.

Intercultural communication can happen in many ways, such as through rebus puzzles that are typically used to gauge critical thinking and problem-solving skills. “Rebus puzzles involve a combination of visual, spatial, verbal, or numerical cues from which one must identify a common phrase or saying” (Threadgold, Marsh, & Ball, 2018, p. 2). In this exercise, I interviewed the participant by presenting him with a rebus puzzle and asking him to interpret its meaning. To coach the participant, I asked questions, rephrased questions, and provided hints in hopes that the participant would quickly solve the puzzle. The purpose of this exercise was to explore the usefulness and easiness of a rebus puzzle to problem-solve. Usefulness and easiness were based on the amount of time it took the participant to solve the puzzle, number of silent pauses, hints provided, and questions asked. The entire experiment, including transcription analysis, took a total of 42 minutes and 46 seconds to complete.

Conducting the Experiment

To begin the experiment, I used a rebus puzzle which is defined as a picture representation of a name, symbol, or phrase. The rebus puzzle comprised of both numbers and letters (See Figure 1):

Figure 1: Rebus puzzle (Answer: “no one understands”)

The participant is a Nigerian male, in his mid-30s, who speaks Igbo as his native language, English as a Second Language (ESL), and Japanese as an Additional Language (JAL). The exchange began with me showing the participant the rebus puzzle, explaining the meaning of a rebus puzzle, and asking him to tell me what he sees.

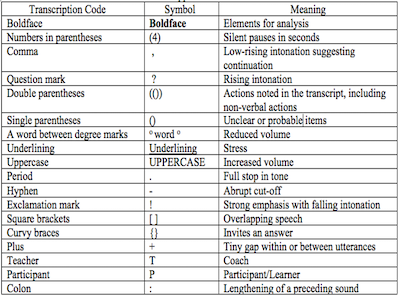

I analyzed the transcription by creating an outline and following Markee’s (2000) transcript conventions (See Figure 2):

Figure 2: Transcript Conventions for CA

The analyzed transcript revealed that there were a lot of silent pauses shown by the participant and coach, overlapping, and frustration, followed by increased volume in voice displayed by the participant. I gave a hint to help the participant figure out the puzzle and continued to prompt him with additional questions, such as “Where are the numbers located?” “Which word is on top?” “What do you see?” After solving the puzzle, the participant lacked motivation to participate in a similar exercise. Again, what I presumed would take seconds to solve actually took the participant 2 minutes and 46 seconds to successfully complete. The analysis showed that the participant had a total of 28 silent pauses and I had a total of 14 silent pauses.

My silent pauses were due to the time it took me to find appropriate questions to ask the participant, but the silent pauses by the participant were seemingly due to a lack of understanding the puzzle. Burns et al. (as quoted in Qi & Tian, 2011) reckoned, “pauses between turns may indicate that a speaker is searching for the correct response or is signaling that an unanticipated response is likely '' (p. 91). The participant mentioned that he was not sure if the puzzle was a code or game, noting that this type of puzzle was a “cultural thing” that he had not learned in Nigeria. I provided a total of six hints to help the participant solve the puzzle, with two of the hints being repetitive statements aimed to enhance the participant’s cognition, and the final hint which ultimately led to the participant solving the puzzle. After the exercise, the participant provided feedback by explaining that the puzzle was a different style of learning from the traditional education he had received in high school. So, what I presumed to be a stress-free, easy to solve puzzle, turned into a frustrating, educational experience for the participant.

Discussion

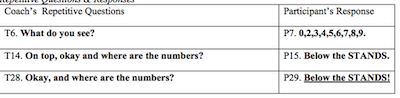

The CA showed that there were only two questions asked more than once and they were “What do you see?” and “Where are the numbers?” The first question, “What do you see?”, was only asked a second time to ensure that the participant believed his provided response. When asked a second time for clarity, the participant quickly changed his response. The question, “Where are the numbers?”, was asked three times as a means of checking to see if the participant was able to solve the puzzle. The second time the question, “Where are the numbers?”, was asked led to the participant raising his voice, and the third time caused the participant to reply with strong emphasis, increased volume, and stressed syllables (See Figure 3):

Figure 3: CA Snippet

A few significant problems were that the participant struggled with my coaching style that entailed repetition and hints. Initially, the participant was unable to comprehend the purpose of my repetitive questions or hints that suggested answers to solving the puzzle. The participant became frustrated and appeared annoyed, because he was unable to immediately solve the puzzle from my provided hints. In addition, the participant did not seek any clarity on the questions that were asked, nor did he initiate any questions to ensure comprehension. The participant depended solely on me to prompt him for an answer and guide him through the puzzle. The participant’s learning approach of this exercise could be the result of a traditional teacher-directed style of learning where student-centered interactions are minimized (Sert & Seedhouse, 2011). My silent pauses took place as a means of determining my next hint or provocative question, while the participant’s silent pauses likely occurred as a means of confusion to solving the puzzle. Based on the participant’s reaction, the selected rebus puzzle was either too difficult to solve or the unfamiliarity of my coaching style was quite perplexing.

Future studies could explore additional factors affecting the participant’s response, such as familiarity with learning/coaching style, type of rebus puzzle (bodily gestures) used, knowledge of participant’s cultural background, or the context the puzzle is introduced in. MacGregor and Cunningham (2009) argued that rebus puzzles incite reading skills and the use of whole words may provide more effective hints. However, while the participant was able to comprehend the whole word “STAND” in the puzzle, he was still unsure of how to conceptualize it as helpful to solving the puzzle. Moreover, the CA indicated that the given hints were not as helpful as expected, which led me to further reflect on my own coaching style and recommendations to others who are considering using CA as a method for engaging culturally-diverse learners.

Implications for Intercultural Communication Educators

Conversation analysis helped to explain reasons and relationships between the amount of time it took before the participant was able to solve the puzzle, number of silent pauses, hints given, and repetitive questions asked during the exercise. Interestingly, the use of repetitive questions became a negative factor that frustrated and possibly discouraged the participant from solving the puzzle in a timely fashion and wanting to engage in similar exercises. Thus, it is highly recommended to learn more about the participant’s educational background first, and practice using rebus puzzles as a preparation component to ensure comprehension of its concept, especially if the intent is to prevent frustration, minimize pauses, and reduce time. It is also recommended to learn more about the participant’s culture as a means of discerning most appropriate rebus puzzles to use. MacGregor and Cunningham (2009) highlighted that “[…]the difficulty of rebus puzzles could be manipulated by systematically varying the restructuring required to solve them” (p. 130). Therefore, creating and using authentic and culturally-referential rebus puzzles are quintessential. In conclusion, the use of rebus puzzles, with CA as a method, provided insight on not only meaning-making between cultures – in terms of learning more about the participant’s learning style and participant learning more about the coaching style – but also a self-awareness of one’s own coaching style and a realization that imagery does not always equate to easiness and usefulness when problem-solving.

References

MacGregor, J.N. & Cunningham, J.B. (2009). The effects of number and level of restructuring in insight problem solving. Journal of Problem Solving, 2(2), 130-141.

Markee, N. (2000). Conversation analysis. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Qi, S. & Tian, X. (2011). Conversation analysis as discourse approaches to teaching EFL speaking. Cross-cultural Communication, 6(4), 90-103.

Sert, O. & Seedhouse, P. (2011). Conversation analysis in applied linguistics. Novitas-ROYAL (Research on Youth and Language), 5(1), 1-14.

Threadgold, E., Marsh, J. E., & Ball, L. J. (2018). Normative data for 84 UK English rebus puzzles. Frontiers in Psychology. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A565570865/AONE?u=kctcsjcc&sid=AONE&xid=6009ae92

Dr. Quanisha Charles grounds her research in narrative inquiry to capture intricate identities that impact how individuals understand themselves within society. Charles has taught the English language in not only the U.S. but also South Korea, China, and Vietnam. Charles is an Assistant Professor of English and TESOL program coordinator at Jefferson Community & Technical College in Louisville, Kentucky. |