|

Elizabeth O’Dowd |

|

Mahmoud Arani |

Author and Audience

If we examine the work of experienced writers, we see that it

involves systematic decisions, from the top-down level of organization

to the bottom-up level of word choice and sentence construction. These

decisions are driven by the author’s relationship with the intended

audience as, for example, in the following two “definitions”:

A: Culture Shock

Culture shock is the effect that immersion in a strange culture

has on the unprepared visitor. It is what happens when the familiar

psychological cues that help an individual to function in society are

suddenly withdrawn and replaced by new ones that are strange or

incomprehensible. (Toffler, 1970, p. 14)

B: Wife

I want a wife whom I can depend on; who will care for me when I

am sick and sympathize with my pain and loss of time from school. . . .

I want a wife who will not bother me with rambling complaints about

those duties which she naturally has to do. But I want a wife whom I can

tell when I feel the need to explain a rather difficult point that I

have come across in my course of studies. And I want a wife to whom I

can give my papers for typing after I have written them. (Syfers, 1971,

p. 56)

These texts address very different audiences. The first aims to

inform a relatively mature and educated reader who is not known to the

author. Accordingly, it shows the conventional construction for a formal

definition: a general classification of the concept, followed by

specific characteristics, and then clarifying details about the events

that make up culture shock. Sentence structures match these functions:

adjective clauses are custom-built for distinguishing characteristics

(“that immersion . . . has on the unprepared visitor”). Passive voice

and abstract vocabulary (immersion, psychological cues,

withdrawn) complete the academic tone.

The second text also addresses an educated, unknown audience,

but in order to amuse. Its success depends on reaching readers who would

find this definition of wife outrageous and

understand its satirical purpose. Written for a feminist magazine, the

shared joke is carefully constructed: Instead of a conventional

definition, we have a long list of assertions, expanded by

distinguishing adjective clauses with a repetitiveness that exaggerates

the blundering insensitivity of their meaning. The irony will not be

lost on female readers who may have heard themselves complaining about

such male insensitivity. The academic-sounding whom/to whom, as well as rather and naturally, is belied by

the consistent use of I (11 times in four

sentences), which suggests the self-seriousness of an oversized ego.

These examples illustrate how both writer and readers need to

co-construct the meaning of a text. In other words, readers must read like writers to interpret the author’s

intention, and authors must write like readers to

anticipate their audience’s response.

How can developing writers learn to do this, especially in a

nonnative language? The answer, we propose, is to bring reading and

writing together in the classroom in a conscious integration. The

reading stage involves text analysis of the type indicated earlier.

Through guided discussion, English learners can appreciate what kinds of

choices make a model text work. Next, through guided drafting in a

joint text construction activity (Derewianka, 1990), they can learn to

emulate those choices. This prepares writers for the final stage:

independent construction, where they approach their own writing with a

reader’s eyes. The rest of this article offers suggestions for the

three-stage learning cycle (Coffin et al., 2003), with an

intermediate-level class.

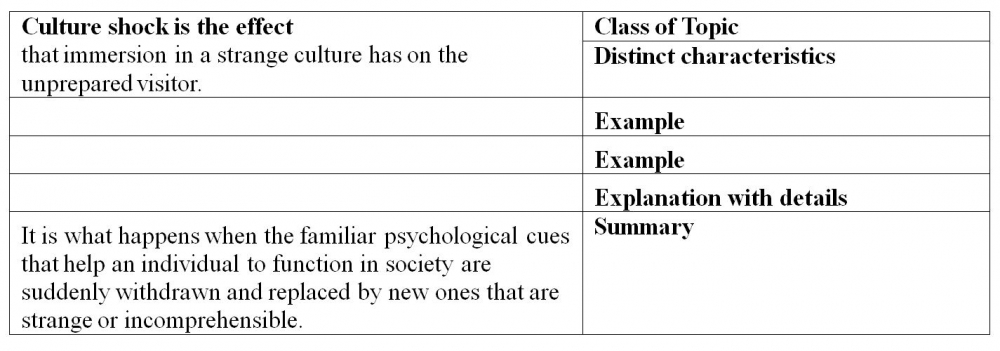

Stage 1: Text Analysis

Focusing on top-down logical organization, students are led to

notice how the culture shock definition is put together logically and

how it may be elaborated through examples and explanations. They might

label the functional parts in the text or, for more engagement,

reconstruct it by choosing and ordering components from the adapted

original, as in Exercise 1.

Exercise 1. Text Analysis: Culture Shock

Here is the definition paragraph that we studied last

week. Expand the paragraph by choosing the three best sentences from the

list below. Make sure your sentence matches the functions on the

right.

- Culture shock is generally not a pleasant experience.

- Peace Corps volunteers suffer from it.

- Culture shock is what happens when a traveler suddenly finds

himself in a place where yes can mean no, where laughter may signify

anger.

- The first stage of culture shock—the honeymoon period—is the easiest.

- Marco Polo probably suffered from it in Cathay.

(Key: Sentences 2, 5, 3 in that order)

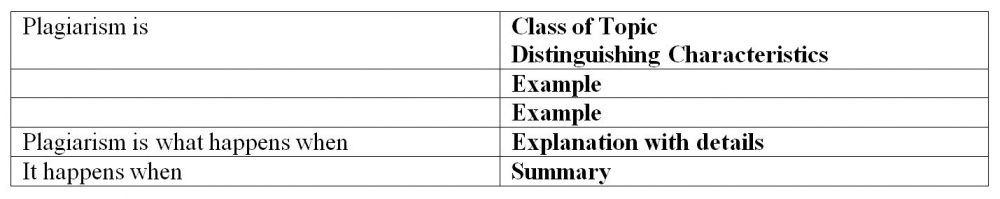

Stage 2: Joint Construction

Having discussed and analyzed the author’s arrangement of ideas

for culture shock, students try making similar decisions themselves for

a text with a similar genre. In Exercise 2, sentence starters

provide a frame but leave content ideas wide open for students to

negotiate in this teacher-led cooperative activity. Thus, less confident

students contribute while listening to the reasoning of stronger

classmates, who are themselves scaffolded by the text they have just

analyzed.

Exercise 2: Joint Construction: Plagiarism

Draft a paragraph following the structure of our

“culture shock” definition. You may expand the paragraph with more

examples and details than you see in the chart.

Stage 3: Independent Construction

During Stages 1 and 2, students have learned rhetorical

concepts such as class and distinguishing characteristics. These will be

used as metalinguistic tools when they write their own definitions and

bring them back to the classroom to share so that peers can read like

writers for each other.

Exercise 3: Independent Construction

Write your own paragraph, defining a behavior or an

experience. Start with the class and the distinguishing characteristics. Use examples and

explanations with details to expand your paragraph. End with a summary.

Some ideas: Success, revolution, respect, addiction.

Bottom-Up Construction

The learning cycle also develops grammar in writing. Exercises

4–6 focus attention on how passive sentences contribute cohesion to a

text by keeping the topic consistently in subject position.

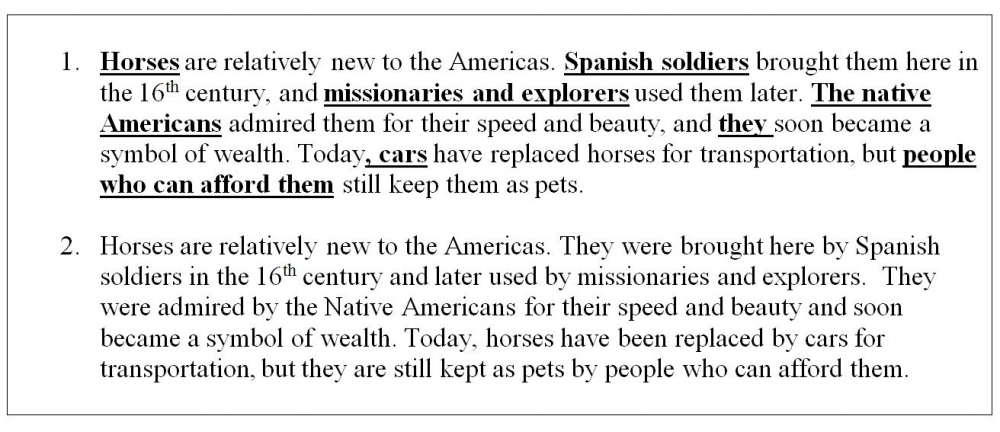

Exercise 4: Text Analysis: Horses in the New World

- Look at the Paragraph 1. The topic is horses. The

paragraph underlines every subject

(first idea) in each sentence. How many different ideas are

underlined?

- Now look at Paragraph 2. Underline the subjects.

How many different ideas are underlined?

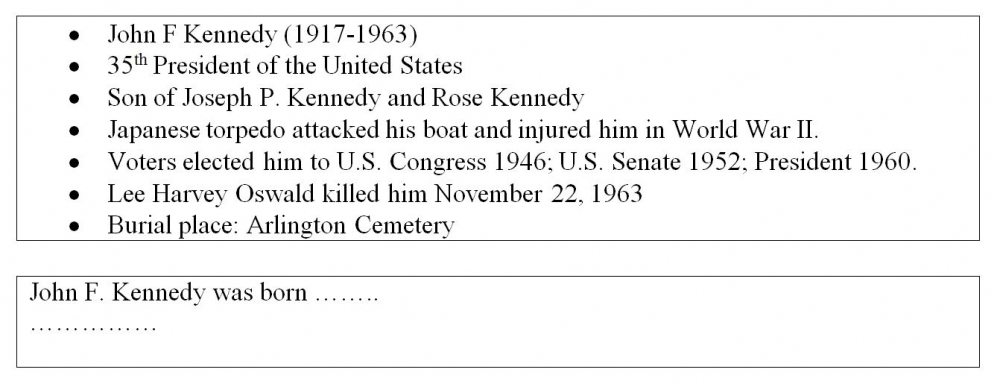

Exercise 5: Joint Construction: JFK

Use these facts about President John F. Kennedy (JFK)

to write his biography. Keep JFK (“he” or “his ___”) as the first idea

in every sentence. Use passive voice where you need

to.

Exercise 6: Independent Construction

Write the biography of a famous person. Keep the

person (“she” or “her ___”) as the first idea in every sentence. Use

passive voice where you need to.

Conclusion

With exercises like these, the learning cycle helps students

become independent writers, by first becoming readers who appreciate

text construction at all levels— in

their own work and in the work of others.

REFERENCES:

Coffin, C., Curry, M. J., Goodman, S., Hewing, A., Lillis, T.

M., & Swann, J. (2003). Academic writing: A toolkit for

higher education. London, England: Routledge.

Derewianka, B. (1990). Exploring how texts

work. Rozelle, New South Wales, Australia: Primary English

Teaching Association.

Syfers, J. (1971). I want a wife. Ms., 1.

Toffler, A. (1970). Future shock. London, England: Random House.

Dr. Elizabeth O’Dowd directs the MATESOL program

at Saint Michael’s College. Her research interests include systemic

functional linguistics as applied to academic reading, writing, and

grammar; teacher collaboration and content-language integration for

English language learners; and World English.

Dr. Mahmoud T. Arani is the chair of the Applied

Linguistics Department at Saint Michael’s College. His general areas of

research interest are second language acquisition, teaching reading and

writing, and the application of discourse/error analysis in teaching

reading/writing and in developing communicative instructional

materials. |