|

Jane Conzett |

|

Lara Dorger |

When we become teachers, we understand that we will provide

learning experiences for students and give them feedback about their

performance. We know that this feedback helps students develop their

skills and informs them of the quality of their achievement. In recent

years, however, an even greater focus on student performance and

achievement has increased assessment expectations of teachers

everywhere. Besides giving formative and summative feedback to students

on how well they meet objectives, teachers must now

- observe and measure students’ ability to meet learning outcomes and

- report and document outcomes and grades to programs, schools, and accrediting bodies.

Focusing on student achievement is important and laudable, and

so today’s “culture of assessment” is likely here to stay. Yet for

teachers in intensive English programs (IEPs), whose classes often meet 5

days per week and whose curricula are ambitious and extensive, these

increased reporting and documentation requirements can become

overwhelming. Students need and deserve timely feedback, but busy

teachers have finite time and energy for additional

documentation.

In our IEP at a university in the midwestern United States, we

began in recent years to feel overwhelmed by the increasing

documentation load. The “intensive” in intensive English program took on

a new meaning for instructors, and we had concern that constant

measurement and evaluation by teacherstook students out of the learning

equation, making them less independent. We decided to devote an

in-service day to assessment issues, and after discussion the faculty

developed our program’s Assessment Vision. In our ideal world, students

receive frequent and timely feedback from multiple sources, and

instructors grade and assess enough to document students’ achievement of

outcomes. In addition, instructors strike a balance in the freedom of

assessment, using as appropriate response, assessment, evaluation, or

grading (Tschudi, 1997). Finally, assessment and evaluation is a

responsibility that is shared by both the teacher and the

student.

As we worked to achieve our vision, we took specific steps:

1. Define Expectations for Frequency of Assessment

How often should we measure whether students meet learning

outcomes? Unless expectations for frequency of assessment are defined by

a program, teachers may be overassessing for their documentation,

leading to stress. At our in-service day, we had a group discussion and

reached consensus about assessment frequency for our specific program

and for our specific learning outcomes. This gives all faculty—both new

hires and senior instructors—benchmarks for assessment frequency.

Focusing our definition on outcomes puts emphasis on student learning,

not on what teachers “do” in the classroom. Here is one

example:

Intermediate-Level Outcome: Student will be able to write a

short essay with rudimentary organization (introduction, body, and

conclusion)

Assessment Type: Program rubric

Frequency: 3-4 times per semester

By setting specific expectations for frequency, we avoid the

possibility that instructors might be underassessing or overassessing.

By defining “enough,” we can prevent instructor overload.

2. Share Ideas and Models for Assessment Types

Great ideas for dealing with the grading load may be close at

hand from your own colleagues. Another agenda item at our in-service day

was to brainstorm and share models for assessment types for all of the

subjects we teach. Then we selected from this list assessment types that

documented observable and measurable outcomes, that saved time, or that

promoted students’ independence and ability to self-assess.All of these

criteria were important to us. Some of the ideas in this article were

gleaned from our program’s meeting.

3. Adopt Technology

Technology can help teachers handle the grading load. In our

IEP, we have used freeware and also programs licensed by our university

to assist us with grading, reporting, and documentation. Engrade is a free online

grade book program we have adopted. ¨Instructors can record grades,

students can see them in real time, and—most significant for us—we can

tag assignments with standards that document specific outcomes. Turnitin and its companion

program, GradeMark

allow us to check for plagiarism and originality; they also allow

instructors to drag and drop their comments onto uploaded student essays

from a customizable comment library. Instructors can also set up their

own rubric in GradeMark or import Common Core rubrics to assess writing. Jing is a

freeware program that allows instructors to make short screencast movies

with audio. An instructor can open a document sent electronically from a

student and use Jing to highlight problem areas while making voice

commentary to explain the issues. Sending the student a link to the

screencast means paperless grading. Camtasia,

the paid version, has more features and capabilities. Using Blackboard, Moodle, or similar learning

environments can also help instructors manage their grading loads when

testing applications are incorporated in the setup.

Technology can also be used to outsource some of the grading

that instructors have to do. Online textbook ancillaries are

increasingly common, and textbook publishers are moving some of their

workbooks online. Intentional adoption of these supporting ancillaries

can lighten the checking and grading responsibilities of teachers and

may be motivating to students.

4. Use Multiple Modes of Assessment and Feedback

Some of the pressure on teachers in today’s culture of

assessment is the time factor—getting feedback to students quickly. The

following strategies can decrease pressure on instructors to “mark and

return” students’ work to them, yet still provide them with timely

feedback:

- Special scratch-off answer sheets, IF-AT (Immediate Feedback

Assessment Technique). These can be used for clear multiple-choice

tests. Students know the correct answer immediately, so instructors have

more time to record scores in the grade book. Anecdotally, students

seem to answer with greater consideration and care. These can also be

used for group tests on which students share a grade, encouraging

greater discussion and critical thinking. IF-AT answer sheets are

available from Epstein

Educational Enterprises.

- Projecting answers immediately after a test or quiz, with PowerPoint or a document camera.

- Online quizzes (with Engrade, Blackboard, etc.). Quizzes are

automatically scored and uploaded to the grade book. These might be best

reserved for low-stakes evaluation and review.

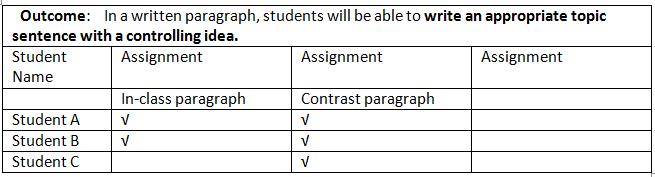

- Rubrics for observable outcomes. Rather than always marking

up and correcting student work, instructors can focus on one outcome and

record whether students met this specific outcome. These are especially

useful for in-class work. Example:

Observed Outcomes Chart

- Portfolios: Items are not formally assessed until students submit a “best of” example.

- Fluency journals (graded: accept/revise): Students gain

experience as writers and spend important time on task without requiring

detailed marking by the instructor. Students can also later revise a

piece of writing in the journal as a graded essay.

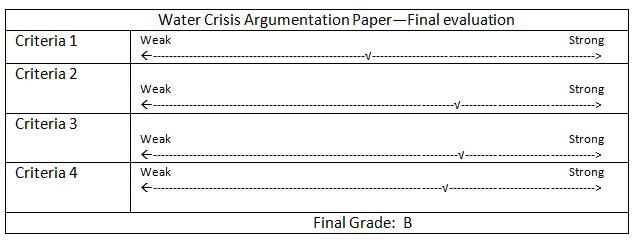

- A summative continuum: After a student submits a first draft

and receives formative feedback according to a specific rubric, final

feedback can be more summative. Example:

Summative Continuum Rubric

- Oral feedback: Instructors can do this in person or with a recording.

- On-the-spot grading: Useful for oral presentations. With a

well-designed rubric, instructors evaluate during class, while students

are speaking.

- Audio and video recordings: Students can view and self-assess with a checklist or rubric

prior to the instructor’s assessment. This is very powerful feedback,

and recordings are also documentation of outcomes.

5. Stack the Deck for Student Independence and Responsibility

The last thing we want to hear students say is, “I haven’t

worked on this anymore because I haven’t received your corrections on my

first draft yet.” Ensuring that students are doing their own part in

achieving outcomes is also a goal of those who wish to “handle the

grading load.” Consider trying the following:

- In a class that focuses on note taking, assess students’

lecture notes every other chapter. Students self-assess on the other

chapters.

- Require multiple drafts of an assignment prior to submission

for final evaluation (giving process points along the way). This can

result in a better final product to grade and evaluate.

- Require students to assess their own work before submission,

with a checklist or rubric. They can include things as basic as “Is your

paper double-spaced? ___yes ___no. Is your Reference list alphabetized?

___yes ___no”—or anything you find yourself correcting over and

over.

- Require students to assess themselves with the assignment

rubric and attach it to the final draft when submitting it. The rubric

can have two columns: one for students, one for the teacher.

- If you do peer editing, support the peer editors with a

checklist to guide them. Have peer editors focus on big-picture ideas

and support, and reserve the grammar feedback for the

instructor.

- Develop a program-wide editing checklist, if you use editing

symbols in feedback, so that students become familiar with them and with

the meta-language.

All teachers share the goal of wanting students to learn and

improve. Documenting this student learning beyond simple grades in

today’s culture of assessment may be time-consuming, but it can be done.

By defining expectations for frequency of assessment, sharing ideas for

assessment collaboratively, adopting technology, using multiple modes

of assessment and feedback, and encouraging student independence and

responsibility, IEPs can strike a balance in grading and assessment.

Teachers can document student learning outcomes as they “handle the

grading load.”

REFERENCES:

Tschudi, S. (Ed.). (1997). Alternatives to grading

student writing. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of

English.

Jane Conzett is the director of the Intensive English

Program at Xavier University, in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Lara Dorger is a longtime Instructor in the Intensive

English Program at Xavier University. |