|

Ryan Lidster |

|

Kate Nearing |

|

Stacy Sabraw |

At our director’s request, the authors formed a Level 1

revision committee in order to bring the courses in line with 2008 curricular reforms, among

which was a qualities scale moving from fluency to clarity/complexity to

accuracy. The rationale for making the change was twofold: 1) There is

great theoretical support for integrated skills and inductive learning;

2) The teacher and student goals were not being met fully in that

course.

Background

When we began the revision process, students met 4 hours per

day for reading and writing instruction (2 hours), oral communication

instruction (1 hour), and grammar instruction (1 hour). The grammar

course format was traditional, explicit practice with grammatical forms,

presented in textbook order. At the same time, our student demographics

were shifting. Several “true beginners” were enrolling each session,

and there was an increase in the number of students not passing as well

as an increase in teacher feedback on students having

difficulty.

We proposed a change in instruction breakdown, which would

retain the 2 hours of reading and writing and give 2 hours for oral

communication. The two overarching goals of “communication” were to

develop fluency and meet students’ survival needs. Features of the new

class included integrated speaking and listening (and other) skills, and

a focus on situated meaning in our local context while also providing

explicit attention to form. Grammar was still incorporated with a focus

on syntax and semantics, and pronunciation was added, including

phonology and sound-spelling correspondence.

Why did we replace explicit grammar? Because studies have shown

that an early focus on fluency helps learners gain access to more of

the language (Brown, 2007; Larsen-Freeman, 200; Murphy & Byrd, 2001). Metalinguistic explanations help more at higher levels

when situated within meaningful content and when they are on a level the

students can understand (Ellis 2006). This was corroborated

by teacher reports and student performance data, which evidenced a lack

of understanding. Our goal was to provide opportunities for explicit

attention to form within classes that focus first on communicative

needs (Snow 2001; Spada & Lightbrown, 2008).

Why did we choose integrated skills?Grammar instruction,

especially at early levels, is more effective when taught as part of an

integrated skill class than as a “discrete skill” (Nassaji &

Fotos, 2004). In addition, many students displayed a gap between oracy

and literacy skills. That is, they use one to “bootstrap” the other, and

it increases the number of ways the language is experienced and/or

processed.

Why did we choose to embed lessons in context? First, providing

personally relevant contexts for language use helps to increase

motivation, salience, and learning rate (Schumann, 2010; Ellis, 2008; Hinkel, 2006). Second, beginners have

immediate, practical needs such as being able to ask for help, providing

basic personal information, or understanding simple instructions.

Practically speaking as teachers, embedding the task makes it easier to

explain.

Why did we include pronunciation? First, according to research (Best & Tyler, 2007), learners show the most improvement in pronunciation in the first few months after arrival. Second, early-level

pronunciation instruction can help improve intelligibility, especially

when embedded in meaningful communication (Bradlow, et al,, 1997; Rvachew et al., 2004). What's more, learners

may use emerging knowledge of the spelling system to help develop new

sound categories, and vice-versa. Further, perfect grammar won’t result

in successful communication if their pronunciation is unintelligible.

Finally, spelling is a pervasive problem that might affect reading,

writing, and even oracy skills.

In concrete terms, we started with student learning outcomes

(SLOs). One of these, for example, is “Use appropriate social greetings,

introductions, and invitations,” which includes “a) Introduce yourself,

and b) Ask and answer questions about personal details such as where

you live, people you know, and things you have and do.” Another SLO is

“Distinguish between singular and plural in the present, past, and

future.” We matched these outcomes to real-life situations that best

illustrate the context (Murphy, 1991) and then determined what language forms were

necessary for successful communication in those contexts.

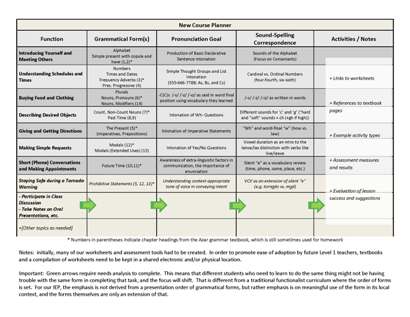

The units in our initial course planner (see the final version

in Figure 1) were based on what functions we anticipated would be of

immediate need for the students.

Figure 1. New course planner (click on image to enlarge)

In Practice: Four Challenges

Once we implemented the new course, we discovered several challenges.

Challenge One: Changing Proficiency

Level.Level 1 is a catch-all for all students below Level 2.

Real Level 1 classes have true beginners, multiple repeaters, orally

proficient speakers with developing literacy skills, and everything in

between.

Our Adaptations:When possible, we assigned different roles,

work, and expectations to higher-level students. Tasks included

extensions and adaptive rubrics for a variety of answers and levels. We

recruited the help of a translator to explain the syllabus and course

expectations (we had a homogeneous L1 population).We also gathered

production data to track what our students were able to do and to what

degree (in the four skills).

Challenge Two: Varying Needs.Not all the

students always needed what we had predicted they would. Some students

were proficient in many or all of the functions in the course planner,

and yet were not ready for Level 2. Also, students’ needs vary depending

on their circumstances (e.g., upcoming registration, visa deadlines,

e-mail notices; IEP trips and community events; or extreme weather and

safety concerns). Our concern was that if new teachers attempted to

follow a prescribed path, they might end up boring or losing

students.

Our Adaptations:In class, we removed and added to functions as

necessary, constantly communicating those changes with each other. For

example, buying clothing was not an immediate concern for our students

in the initial sessions. However, accepting and declining invitations

had been overlooked and came up unexpectedly often. In addition,

communicating via e-mail and being able to use campus computers is a

real need.

Challenge Three: Form Accountability.

Focusing on fluency alone may promote the use of non-target-like forms

because they work (e.g., “I am no understand” or “Can you again

teacher?”). Also, students who are able to complete the task and acquire

the necessary information may self-assess as proficient in the

form.

Our Adaptations: We designed activities where a degree of

accuracy in the form is needed to achieve the function (Bigelow, Ranney, & Dahlman, 2006). We used

activities such as information relays and presentation preparation. Even

for basic fluency activities, we included a “reduced degree of freedom”

(Gibbons, 2002). Our assessments attempted to measure task

completion as well as attention to the form.

Challenge Four: Passing the Baton.Embedding

instruction in local, immediate needs means that teachers have to make

many materials and this requires experience and time. In addition, new

teachers needed a transparent way of understanding the curriculum and

adapting it to their needs. (Our course originally used the Heinle Picture Dictionary with an open, flexible design that

was intimidating to some.)

Our Adaptations:After we had tested out the curriculum, we

found supporting textbooks and materials (e.g., Cambridge’s Touchstone

series) and previous worksheets and activity types were collected in an

electronic folder. Teacher feedback and student performance data are now

updated on an ongoing basis.

The Final Product

Our syllabus (i.e. the course planner) is open to teacher

adjustments, while still providing specific details and structure.

Because Level 1 is such a moving target, we found this met our needs

well. Also, the new syllabus provides ample opportunities for

meaningful, authentic communication and inductive learning. Asking,

“What do they need to be able to do?” helped greatly in guiding material

selection and specific lesson planning.

Other programs attempting to reform their curriculum would

benefit from similar course designs because: 1) there is theoretical

support for integrated skills and a focus on inductive learning for

beginners, and 2) an adaptive, context-based syllabus better matches

beginning students’ real-world needs. Accepting this level of

flexibility may be intimidating. However, flexibility does not mean a

lack of structure. Course planners are even easier to implement than a

traditional syllabus after an adjustment period. What’s more, the

students’ needs are not static, and teacher discretion is necessary

regardless of course design.

Conclusion

Our new course design better matches our program’s goals and

students’ needs. It is highly communicative, focused on relevance to

real life, and promotes integrated skill development. Although it is a

work in progress, we believe many of the lessons learned from this

process are relevant to other IEPs, and other levels as well.

REFERENECES

Best, C. T., & Tyler, M. D. (2007). Nonnative and

second-language speech perception: Commonalities and complementarities. Language experience in second language speech learning: In

honor of James Emil Flege, 13-34.

Bigelow, M., Ranney, S., & Dahlman, A. (2006). Keeping

the language focus in content-based ESL instruction through proactive

curriculum-planning. TESL Canada Journal, 24, 40–58.

Bradlow, A. R., Pisoni, D. B., Akahane-Yamada, R., &

Tohkura, Y. I. (1997). Training Japanese listeners to identify English

/r/ and /l/: IV. Some effects of perceptual learning on speech

production. Journal of the Acoustical Society of

America, 101, 2299-2310.

Brown, R. (2007). Extensive listening in English as a foreign. Language Teacher, 31,

15-18.

Ellis, R. (2008). The Study of Second Language

Acquisition. 2nd edition. Oxford:Oxford

University Press. (pp.729-769).

Ellis, R. (2006). Current issues in the teaching of grammar: an

SLA perspective. TESOL Quarterly, 40, 83–107.

Gibbons, P. (2002). Scaffolding language, scaffolding

learning: Working with ESL children in the mainstream elementary

classroom. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Hinkel, E. (2006). Current perspectives on teaching the four

skills. TESOL Quarterly,

40¸109-131.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2000). Techniques and principles

in language teaching (2nd ed.). Oxford,

UK: Oxford University Press.

Murphy, J. (1991). Oral communication in TESOL. Integrating

speaking, listening and pronunciation. TESOL

Quarterly, 25, 51–75.

Murphy, J., & Byrd, P. (Eds.). (2001). Understanding the courses we teach: Local perspectives on

English language teaching. Ann Arbor, MI: University of

Michigan Press.

Nassaji, H., & Fotos, S. (2004). Current developments

in research on the teaching of grammar. Annual Review of

Applied Linguistics, 24, 126–145.

Rvachew, S., Nowak, M., & Cloutier, G. (2004). Effect

of phonemic perception training on the speech production and

phonological awareness skills of children with expressive phonological

delay. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology,

13, 250-263.

Schumann, J. H. (2010). Applied Linguistics and the

Neurobiology of Language. In R.B. Kaplan (Ed.), The Oxford

Handbook of Applied Linguistics, 2nd edition (pp.244-259).Oxford:Oxford University Press.

Snow, M. (2001). Content-based teaching. In M. Celce-Murcia

(Ed.). Teaching English as a second or foreign language,

3rd Edition (pp. 303-318). Boston, MA:

Heinle & Heinle.

Spada, N., & Lightbown, P. (2008). Form-focused

instruction: Isolated or integrated. TESOL Quarterly, 42, 181–207.

Ryan Lidster is a PhD second language studies student from

Vancouver, Canada, with experience in Japanese EFL, French FL, and

French immersion instructional environments. His interests include

assessment design, washback, language policy, teacher training,

materials development and use, L2 phonological acquisition, dynamic

assessment, and Complex Systems Theory.

Kate Nearing has an MA in second language studies from

Indiana University. She now teaches for the Intensive English as a

Second Language Program in the Department of Humanities at Michigan

Technological University. Her interests include understanding research

and practice as they relate to phonetics, phonology, and

pronunciation.

Stacy Sabraw has an MA in TESOL and applied linguistics from

Indiana University. She now teaches in the English Language Center at

Michigan State University. Her current research is on the integration of

assessment and instruction in second language pedagogy, and the needs

of students as they transition from a language program to mainstream

university. |