|

In her keynote at the ITA Professional Symposium (The ITA

Professional Symposium was hosted by Carnegie Mellon University in

February 2017), Lauren Herckis referred to culture and teaching as

“invisible.” During the Q and A, I questioned her use of the term, but

the metaphor of invisibility re-emerged throughout the remainder of the

discussion showing that many in attendance agreed with the idea that

culture, language, and teaching are invisible. I found this stance

ironic considering the common practice in our field of using of video

and transcription. In fact, the issue that our ITAs face is not that

language and teaching are invisible. It is that language and teaching

are in the moment happenings that cannot be recovered verbatim from

memory. In addition, potential ITAs often lack the conceptual framework

and tools to analyze, discuss, and reflect upon teaching and

interaction.

In this article, I will briefly discuss the use of video and

transcription to make language and teaching visible. I will then analyze

a transcribed excerpt from a university mathematics course, drawing

attention to the interplay between prosody and gesture, and discuss how

the excerpt might be used in ITA preparation. I point out that while

language and teaching may be evanescent in the moment they are

nonetheless visible and made re-visible through the use of video and

transcription. Finally, I suggest that we do ourselves a disservice as a

profession by being lackadaisical in how we talk about language and

teaching.

Using Video to Make Language and Teaching Visible

The use of video has been suggested by or part of commercially

available texts for ITA preparation for decades (Gorsuch, Meyers,

Pickering, & Griffee, 2012; Meyers & Holt, 2002; Smith,

Meyers, & Burkhalter, 1992). Videos and transcripts are

particularly valuable resources for two reasons: they lend permanence to

language and teaching, and they enable us to highlight embodied

resources. First, they make the fleetingly audible and visible, i.e.,

language and teaching, re-visible. As Garfinkel (2002, p. 220) pointed

out in his study of a university Chemistry lecture, the action of the

classroom “cannot seriously be identified, formulated, or solved”

without “analyzable audio and video documents.” The details of language

and teaching are difficult to reconstruct from memory, but a digital and

written record of language and teaching gives us the ability to watch

and re-watch and analyze and re-analyze sequences of classroom

interaction. When we watch videos, we are able to notice even those

actions we missed in situ. Video and transcripts solve our dilemma with

the evanescence of language and teaching, so our next objective becomes

giving our students the concepts and vocabulary to analyze and reflect

upon what they see, and in turn to hopefully integrate (or not) what

they have seen into their own teaching.

So that becomes our task – developing a framework and lexicon

for our students to use to think and talk about language and teaching.

While ITA research and practice have developed robust frameworks for

understanding and teaching prosody (Gorsuch et al., 2012; Hahn, 2004;

Kang, Rubin, & Pickering, 2010; Meyers & Holt, 2002;

Pickering, 2001, 2004; Smith et al., 1992) embodiment is not well

researched in the ITA realm, which is likely the source of early

descriptions of lab interactions as “messy” (Myers, 1994). While some

face-to-face classroom situations may seem messy when we focus only on

lexis and morphosyntax, Goffman (1964, p. 136) observed that

“interaction […] has its own processes and its own structure, and these

don't seem to be intrinsically linguistic in character, however often

expressed through a linguistic medium.” From an embodied perspective,

participants interact not just through talk, but through mutual

orientation to a “temporally unfolding juxtaposition of multiple

semiotic fields,” including prosody, gesture, gaze, body position, and

the use of classroom artifacts (Goodwin, 2000, p. 1517; Mondada, 2016).

Video gives us direct access to the embodied resources used in teaching

that are often overlooked when we focus on language only in terms of

lexis and morphosyntax. As ITA trainers, we must draw our students’

attention to the “complex multimodal Gestalts” (Mondada, 2016) formed by

the co-occurrence of talk, gesture, gaze, facial expression, and the

use of objects in the environment. In the following two sections, I will

discuss how we can do so.

A Brief Analysis of Prosody and Embodiment While Introducing a Term

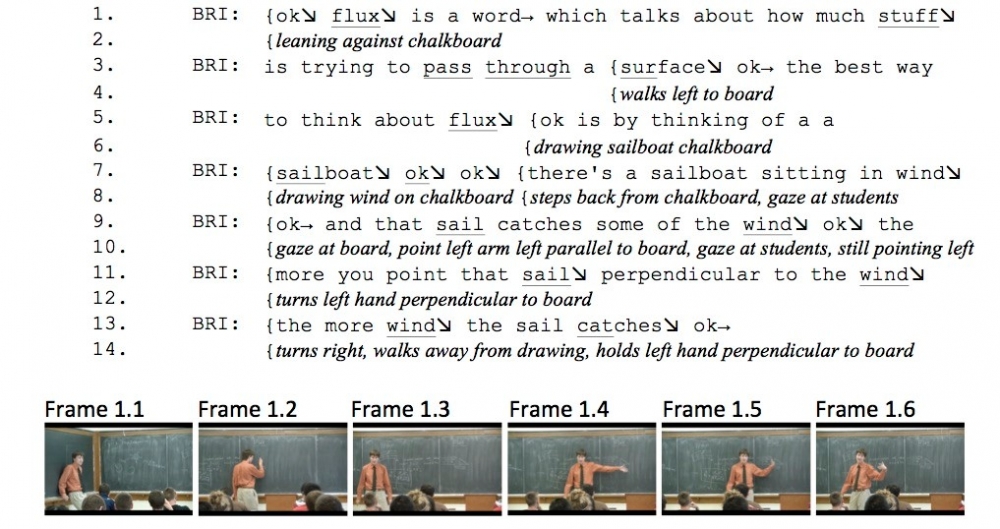

Excerpt 1 is from a university calculus course taught by Brian

(pseudonym). For more explanation of the broader study, participants,

etc., see Looney, Jia, and Kimura (2017). The analysis unpacks how Brian

uses various linguistic and non-linguistic resources to explain a

field-specific term. The excerpt occurred near the opening of an

explanation of the term “flux.” During Brian’s introduction of the term,

he enacts many suggestions for teaching that we see in the

aforementioned ITA training texts, e.g., use concrete examples, clear

thought groups, and multimodal resources. In Excerpt 1, the

transcription conventions note final falling and continuing rising tones

(↘ and →), prominence (underlined text), and embodied resources

(aligned with talk by { and written in Times New Roman). While the

excerpt presented here is short, the actual explanation of the term is

quite long and involves multiple concrete examples.

Excerpt 1 – “Flux is a word"

Click to enlarge

Just before Excerpt 1, Brian was leaning against the chalkboard

and informally introducing the term flux in the context of a popular

science fiction movie from the 1980’s (Frame 1.1). Brian then gave a

brief definition of flux in lay terms (lines 1 and 3). Note the stress

and falling intonation that he placed on the words flux, stuff, pass

through, and surface to create distinct intonational units and highlight

new information (Pickering, 2001).

As Brian concluded his layperson definition, he walked toward

the chalkboard and began drawing a sailboat (lines 4-6, Frame 1.2). As

he was drawing, Brian verbally presented students with the concrete

example of a sailboat (lines 3-7). Even though he was facing away from

the students momentarily, Brian spoke in clear thought groups and used

intonation to emphasize key information. He then turned back to his

students and began expanding upon his example (lines 7-8, Frame 1.3). In

lines 8-13, Brian stated that the more perpendicular the sail is to the

wind the more wind the sail catches. As he was speaking, his hand first

pointed in the direction of the wind he had drawn on the board then he

turned his hand, representing the sail he was speaking of, perpendicular

to the wind (Frames, 1.4, 1.5, 1.6). In sum, we can subdivide the above

excerpt into three moves: layperson definition, introduction of

concrete example, and explanation of concrete example. We see that Brian

used linguistic, prosodic, and embodied resources to construct his

explanation. Prosodic and embodied resources, i.e., intonation, stress,

gesture, and the chalkboard, were particularly important because they

subdivided and highlight important information.

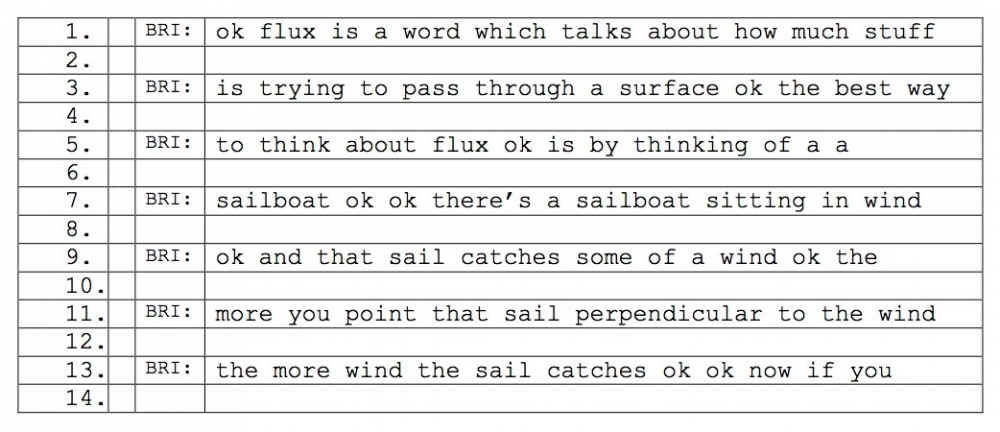

From Analysis to Application

This analysis, though brief, is useful for teachers trying to

help potential ITAs see and discuss language and teaching. While a

detailed transcript is useful for the teacher and eventually the

student, I suggest starting with a broadly transcribed transcript with

line numbers and space for students to make notes (see Excerpt 2).

Courier New is a great font for making transcripts because each letter,

symbol, and space are the same width. The line numbers and simplified

transcription create an artifact that students can use to code different

parts of the explanation. For instance, we could code lines 1 and 3 as

“layperson definition,” lines 3-7 as “introducing a concrete example,”

and lines 7-13 as “expanding upon a concrete example.”

Excerpt 2 – “Flux is a word” for classroom use

Click to enlarge

Within the subsections that we have identified, we can analyze

and discuss prosody and embodied resources. This is where the vocabulary

from discourse intonation and CA will be particularly handy. In terms

of prosody, there are three features that I find this clip particularly

useful for: thought groups, prominence, and final falling (or

rising-falling) intonation. Students can work in groups or individually

to identify the thought groups, prominent words, and intonation

contours. Students can also identify and describe the embodied resources

they notice. This excerpt would be particularly useful for explaining

and analyzing the use of the chalkboard and gesture. After students have

completed their analyses, have them share and discuss them as a class.

This is where the detailed transcript in particularly useful especially

because it illuminates the complex interplay between talk and embodied

resources. After the discussion, students can use their analysis as a

micro-template for their own assignment of introducing a term or

concept. There could be other uses for this recording as well, e.g., a

fluency exercise using shadowing. In addition, video can be a useful

tool for helping provide feedback on ITA performance in role plays and

micro-teaching.

Conclusion

Conversation Analysis and related disciplines such as

interactional sociolinguistics and linguistic anthropology have made

readily apparent that language and teaching are visible and analyzable.

At the same time, ITA practice has, if only implicitly, reflected the

stance that language and teaching are visible by using video recordings.

Nonetheless, we are prone to speak of language as invisible because of

its apparent evanescence in our day to day existence. While words like

invisible are easy to use to describe language, we do so at our own, as

well as our students’, peril. Calling language and teaching invisible

perpetuates myths about language and teaching as individual and innate

traits instead of culturally-situated actions and practices that can be

developed through structured mediation. Adjectives like unappreciated or

unnoticed better describe language and teaching, and would be more

useful for us when speaking to those outside ITA practice. As language

teachers who often work with relatively high proficiency learners, it is

our responsibility to provide students with the concepts and terms to

analyze, reflect upon, and discuss language and teaching. We must help

them talk and think about what they see every day. We are not helping

them see the invisible, but helping them notice the

overlooked.

References

Garfinkel, H. (2002). Ethnomethodology’s Program:

Working Out Durkheim’s Aphorism (A. W. Rawls Ed.). New York:

Rowan and Littlefield.

Goffman, E. (1964). The neglected situation. American

Anthropologist, 66(6/2), 133-136.

doi:10.1525/aa.1964.66.suppl_3.02a00090

Goodwin, C. (2000). Action and embodiment within situated human

interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 32, 1489-1522.

Gorsuch, G., Meyers, C., Pickering, L., & Griffee, D.

(2012). English Communication for International Teaching

Assistants (Second ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland

Press.

Hahn, L. D. (2004). Primary stress and intelligibility:

research to motivate the teaching of suprasegmentals. TESOL

Quarterly, 38(2), 201-223. doi:10.2307/3588378

Kang, O., Rubin, D. L., & Pickering, L. (2010).

Suprasegmental measures of accentedness and judgments of language

learner proficiency in oral English. The Modern Language

Journal, 94(4), 554-566.

doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2010.01091.x

Looney, S. D., Jia, D., & Kimura, D. (2017).

Self-directed okay in mathematics lectures. Journal of

Pragmatics, 107, 46-59. doi:https://doi.org

/10.1016/j.pragma.2016.11.007

Meyers, C., & Holt, S. (2002). Success with

Presentations. Burnsville, MN: Aspen Productions.

Mondada, L. (2016). Challenges of multimodality: Language and

the body in social interaction. Journal of Sociolinguistics,

20(3), 336-366.

Myers, C. L. (1994). Question-based discourse in science labs:

issues for ITAs. In C. G. Madden & C. L. Myers (Eds.), Discourse and Performance of International Teaching

Assistants (pp. 83-102). Alexandria, VA: Teachers of English

to Speakers of Other Languages.

Pickering, L. (2001). The role of tone choice in improving ITA

communication in the classroom. TESOL Quarterly,

35(2), 233-255. doi:10.2307/3587647

Pickering, L. (2004). The structure and function of

intonational paragraphs in native and nonnative speaker instructional

discourse. English for Specific Purposes, 23(1),

19-43. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0889

-4906(03)00020-6

Smith, J., Meyers, C., & Burkhalter, A. (1992). Communicate: Strategies for International Teaching

Assistants. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Stephen Daniel Looney is the ITA Program Director and

Senior Lecturer in the Department of Applied Linguistics at Penn State.

He is the current Chair of the ITA-IS, and his research focuses on L1

and L2 use in the university STEM classroom. |