|

Lara R. Wallace

Ohio University, Athens, OH, USA |

|

Yu-Ching Chen

Ohio University, Athens, OH, USA

|

Think back to a time when you played a musical instrument.

Imagine touching the instrument and hearing the resulting sound. What

made the notes high or low? Long or short? Legato or staccato? At the beginning of the semester, the

instructor asks international teaching assistants (ITAs) to recall these

experiences that are then used as an analogy to understand and learn

pronunciation patterns. Many ITAs are familiar with an instrument, and

for those without experience, online piano keyboards (e.g., Virtual

Keyboard) can provide that first encounter. ITAs reflect on

what they did to attain their skill level with the instrument, and the

conclusion is always “PRACTICE!” This of course begs the questions, “How

did you practice? Did you improve by watching music videos or listening

to music featuring your instrument?” Most ITAs laughingly reply “no,”

agreeing instead that regular and thoughtful practice is necessary

because listening alone is insufficient.

Music is processed in multiple parts of the whole brain; there

is not a single “musical center” in the brain, as traditionally believed

(Taylor, 2010, p. 82). However, there are areas in the brain that are

specifically sensitive to different musical elements, such as rhythm,

melody, tone, sequence, and timbre. When the brain processes language,

areas that process similar elements in music are stimulated, such as

intonation (melody), sequence, and rhythm. This is why music is a great

medium for language learning. In this article, we share some ways we

have incorporated music into the teaching of pronunciation.

Effective Practice, Consonants, and Vowels

The analogy of learning a musical instrument can be used as a

guide for effective practice. Much like how ITAs must practice on their

own in order to perform well, a symphony cellist also must do the same.

When she needs to rehearse a difficult passage, she cannot expect to

learn it by playing through the entire piece; rather, she will break it

down into smaller parts, identifying where exactly she needs to improve.

Perhaps it is a difficult jump between two notes, or perhaps she is

struggling to reach the target presto speed in a

particular passage. Either way, she needs to understand the technique

behind the physical act of fingering the notes in order for the motion

to be efficient and the sound to be accurate. She might video-record

herself or use a mirror for clues on how to improve her physical

technique, or she might listen to the recording of her playing to more

clearly hear what she sounds like, maybe comparing it to a model that

she would like to emulate. She might also work with a teacher or

colleague for more feedback.

These actions are not unlike what ITAs do when learning

consonants such as /θ/. It might be easy enough to say “thank you” in

isolation, but producing it in fast speech or overcoming fossilization

due to years of saying “sanks” rather than “thanks” might prove more

difficult. The ITA will first have to understand how to produce this

voiceless interdental fricative. Looking in a mirror and comparing how

much of the tip of the tongue should be sticking out to what the ITA

sees when native speakers produce the sound will help the him visually

understand (the University of Iowa has a good

model online). Listening back to recordings in which the ITA

repeats words containing that sound after a model (e.g., Merriam-Webster online

dictionary) will help him hear any differences. Feeling where

the tongue and teeth make contact when producing the sound accurately

will help the ITA understand kinesthetically. Pronunciation teachers and

tutors can provide additional feedback, affirming when the ITA

pronounces the target accurately and giving instructive feedback on what

to do differently when production is inaccurate.

After production at the small-scale level is achieved, the

cellist, like the ITA, must practice it repeatedly, methodically, and

mindfully, to build the correct mechanics into her muscle memory. Once

she can do so consistently, she can play more of the passage leading

into the difficult section; or for the ITA, words containing the target

sound can be placed into the context of sentences. After such mindful

practice, the cellist will be able to play the passage deftly and

without problems within the context of the piece as a whole, just as the

ITA will be able to produce the sound accurately in focused free

speech. This picture of effective practice can also be applied to

suprasegmentals.

Intonation and Prominence

Pitch movement at the end of a sentence can convey not only

whether the speaker is asking a question or making a statement, but

also, as Gorsuch, Meyers, Pickering, and Griffee (2013) point out,

whether the speaker is sharing new information, routine information, or

reminding listeners of something they previously shared. Tone choice at

the sentence level can convey the speaker’s emotion and whether he seems

friendly or distant; key (paragraph-level tone choice) can signal to

the listener the start or end of a topic. When prominence (higher pitch,

longer length) is placed on key words in a phrase, the speaker

communicates the word’s importance to the listener, and can also signal

that this is new information, or highlight contrasting information.

Consequently, ITAs with a narrow pitch range have difficulty

communicating such assumptions, emotions, and subtle textual

organization cues.

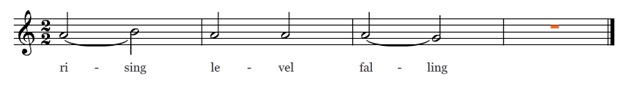

Music can help ITAs both hear and understand pitch movement and

key as well as broaden their range of intonation. For this, instructors

can use three consecutive keys on the virtual keyboard to illustrate

rising, level, and falling pitch at the end of sentences, having the

students match the notes with their voices as they say “ri-sing, le-vel,

fall-ing,” as you can see in the following measures.

To demonstrate key and tone choice further, the instructor can

play the three (white) keys on the right side of the keyboard to

illustrate the high key, the four middle keys as the middle key, and the

four keys on the left as the low key.

The ITAs can again emulate a corresponding high note on the

keyboard when starting a topic (↑“ToDAY, we’ll discuss . . .”) and a low

note when ending a topic (“No questions? ↓Let’s move on.”). For an

added cue, ITAs can raise their arms above their heads when using or

listening to the high key, hold their arms out at chest level for the

middle key, and lower them to their sides for the low key. For

broadening one’s intonation range, these visual cues are helpful for

ITAs to identify their narrowed range of intonation. In fact, ITAs can

learn to distinguish intonation ranges by doing vocal exercises (similar

to choral warm-up exercises) with these hand and arm movements, then

apply this awareness of range to their own speech patterns when the

instructor visually reflects the ITAs’ intonation range. Thus, ITAs can

change their intonation range spontaneously according to the

instructor’s gestures.

Rhythm and Rate

Both musicians and ITAs can practice with a metronome to work on

rhythm and rate. Activities in which there are the same number of

stressed syllables but differing numbers of total syllables (Lane, 2005)

work well when a metronome provides this constant beat. For example,

set the metronome at 88, and stress the words on the beat as in the

following example:

| | |

Stress your WORDS / on the BEAT.

Once ITAs can do this, it is easy to work on linking and

reduction in the thought groups and equally easy to adjust the tempo in

order to help ITAs speak more quickly or slow down as needed. Using the

metronome can also help with thought group division or pausing between

thought groups as marked in the example above.

Thought group division can also be illustrated by playing a few

bars of a familiar tune such as “Hey, Jude” by the Beatles. When

singing “Hey, Jude,” the phrasing of the song naturally prompts ITAs to

pause and breathe between sentences. The physical exercise of breathing

and pausing with the music can then be successfully transformed back to

speaking sentences. Well-known songs like this can also help to

illustrate problems with thought group division, such as “endless

sentences” (failure to pause at the appropriate place) and “split

thought groups” (pausing in an inappropriate place; Gorsuch et al.,

2013, p. 14). To clarify this idea further, ITAs can mark pauses on song

lyrics then sing them back. It is easy to then move from music to

speech by marking transcripts (/) from TED Talks speakers, then

reading them back. Used both as the basis of an analogy and in actuality

by singing or tapping beats, music can be a bridge to understanding and

putting into practice new pronunciation patterns in English.

References

Gorsuch, G., Meyers, C., Pickering, L., & Griffee, D.

(2013). English communication for International Teaching

Assistants (2nd ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland

Press.

Lane, L. (2005). Focus on pronunciation 3. White Plains, NY: Pearson Education.

Taylor, D. B. (2010). Biomedical foundations of music

as therapy (2nd ed.).Eau Claire, WI: Barton.

Lara R. Wallace, a lecturer and the ELIP Pronunciation Lab

coordinator in Ohio University’s Department of Linguistics, earned a BA

in Spanish with minors in music and anthropology, an MA in linguistics,

and is a PhD candidate in cultural studies of education at Ohio

University. Her research interests include ITAs, pronunciation, oral

communication, and CALL.

Yu-Ching Chen, MT-BC, is a board-certified music therapist,

certified neurologic music therapist, music therapy graduate student at

Ohio University, and has a BFA in voice performance. Her research

interests include medical music therapy, multicultural music therapy,

and incorporating music to facilitate language learning for

international students. |