|

Prince George’s County Public Schools (PGCPS) is situated east

of Washington, DC, with more than 129,000 students. PGCPS is the 21st

largest school district in the United States and the second largest in

Maryland in student enrollment. There are 19,000 staff members serving

PGCPS. The PGCPS ESOL Department employs more than 400 educators to

support our 21,000 English for speakers of other languages (ESOL)

students in grades K–12. As a district with more than 200 schools

located throughout urban, suburban, and rural settings, we offer

students a wide variety of programs. Amidst the diverse geography and

student body there are 39 schools with fewer than 12 ELLs that need

educators to provide ESOL instruction. Prior to the Instructional Lead

Teacher (ILT) team formation, ESOL students at these 39 schools were

monitored by ESOL central office staff.

Principals determine staffing needs through a process called

student-based budgeting. For schools with 12 or fewer ELLs, hiring an ESOL teacher—even part time—is not feasible. The need to provide more consistent instruction in our smaller ELL populated schools became a priority. In 2014, an ESOL ILT team of 6 ESOL teachers was formed, through an application process, to create teacher leaders who could work collaboratively with general educators and other specialists while addressing the needs of ELLs in schools with few ELLs. Recent case studies have affirmed that collaborative practices and coteaching arrangements are successfully replacing ESL pull-out services throughout the United States (Pardini, 2006; Zehr, 2006.

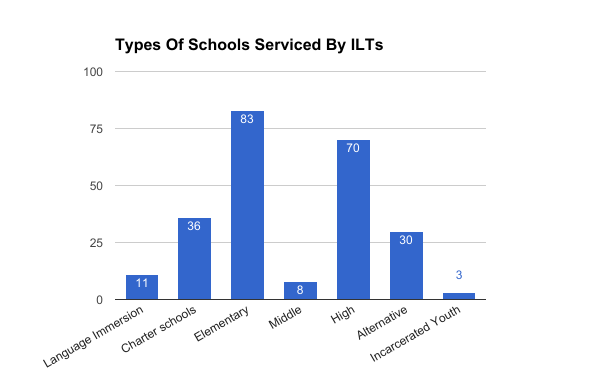

Figure 1 below shows the total number of students provided ESOL services as well as the types of schools where service occurs. Schools with 12 or fewer ELLs were determined through our Student Based Budgeting process every April. During this time, principals determine their staffing needs. Schools showing 12 or fewer ESOL students are deemed to be served by ILTs. Budgets do not include a full time ESOL teacher. Due to rising numbers of ESOL enrollments, Figure 1 shows some schools with over 12 ESOL students enrolled. If a school's ELL population rises after staffing decisions are made, ILTs continue to service schools in spite of the increased enrolments.

Figure 1. Types of schools serviced by ILTs

(x-axis: number of students; y-axis: type of schools)

ILT Responsibilities

The three main roles ESOL ILTs serve include providing direct

instruction to ELLs in Grades K–8, collaborating with mainstream

classroom teachers and other school staff, and ensuring students’

linguistically diverse needs are met.

Specifically, in delivering instructional support, ILTs

-

provide direct K–8 instruction in a variety of school settings;

-

consult with and coach classroom teachers, as desired by mainstream teachers;

-

facilitate professional development at schools, by request; and

-

budget for supplies (classroom materials and technology).

Each ILT travels to between six and eight schools and serves 25

to 40 students. ESOL instruction is driven by data as well as aligned

with district curriculum. ELLs attend public schools, public charter

schools, alternative educational facilities (including incarcerated

youth) for Grades 6–12, talented and gifted schools, Montessori schools,

and language immersion programs. Some ILTs have regular space for

instruction where they are permitted to store materials, while others

fill up their vehicles with materials and wheel their supplies in and

out each visit. To incorporate technology into lessons, ILTs maintain

five Chromebooks each along with Nooks and iPads.

PGCPS reclassified ELLs (RELLs) have exited the ESOL program

and are no longer required to sit for the annual proficiency assessment;

however, students’ progress is monitored by central office leadership in the district as well as by ESOL teachers. For RELLs who attend schools serviced by ILTs, the ILTs meet with RELLs' classroom teachers during a collaborative session. If teachers are unavailable to meet face to face, ILTs send emails to all classroom teachers identifying the RELL students requesting teachers keep in touch with ILTs if students are not showing progress. Classroom teachers and ILTs monitor students’ progress by reviewing assessment data as well as observations of classroom performance. If necessary, ILTs meet with RELLs to determine what additional supports may be needed. When necessary, ILTs consult with classroom teachers and suggest appropriate supports. RELLs are monitored for 2 years after exiting from ESOL services.

Collaboration

ILTs also engage with families to ensure students are

progressing. Parents are a valued part of our students’ educational team

and are included in all aspects of their child’s school experience.

ILTs contact them through phone calls, emails, and text messages, and

communicate with them during parent/teacher conferences. ILTs host

coffee chats and family nights, and have a table at Back to School

Nights with specific resources relating to ELL needs.

Throughout the year, ILTs meet monthly as a team to cover

agenda items such as determining how to incorporate new district

policies into ILT positions, sharing ideas to streamline positions, as

well as solving problems together. Another important ILT collaboration

occurs with classroom teachers in Grades K–12. Because ILTs are not

available to service students 5 days a week, they often plan instruction

with and coach classroom teachers in the language acquisition process

so that students still receive comprehensible input for their in-class

lessons.

Additionally, ILTs collaborate with ESOL central office staff

and other related departments on district-level projects in order to

incorporate expertise that builds capacity for all. ILTs assist with

processes such as testing and registration at the International Student

Counseling Office. ILTs are also called upon to support programs through

parent involvement events.

Examples of projects that ILTs have collaborated on include:

-

Family reunification workshops

-

Designing and facilitating professional development at the school level

-

Kinder Connect (pre-K preparation program)

-

Collaborating and facilitating for district-wide professional development

-

Curriculum writing

-

Various functions at ESOL job fairs

-

Interviewing ESOL teacher candidates

Collaboration with teachers and parents allows ILTs to ensure

they are meeting the whole child’s needs. In order to ensure students’

needs are met, ILTs:

-

connect students, teachers, and families with resources;

-

share best practices in schools with few ELLs; and

-

monitor students’ progress and adjust instructional levels as needed.

ILTs and High School Students

Technology supports allow ILTs to deliver lessons using

programs, such as Reading A to Z kids and Imagine Learning, for

individual language growth. Collaboration between ILTs and high school

students often continues even when the teacher is not at the school

through collaboration tools such as Google Classroom.

High school students are primarily serviced on a consult model; these students are choosing to attend their boundary school instead of an ESOL academy location. A student's boundary school is the school students attend based on their home address. Approximately 15 ESOL High School Academy locations are set up to provide ESOL services for students from various boundary schools. At the high schools serviced by the ESOL ILTs, there are typically very few ESOL students because the majority of our lower proficient ESOL students choose to be bussed to the closest ESOL Academy in order to receive English acquisition support five days a week. Therefore, the majority of ESOL students at ILT-served high schools are considered intermediate or advanced proficiencies. Comprehensible input at ILT-high schools is primarily the responsibility of the mainstream teachers and individual students advocating for their own learning. ILTs make initial contact, meeting with students to explain how ESOL service works at the high school level. Many students choose to contact ILTs for support with college application processes and project-based assignments. Google Classroom is also used to post articles and facilitate discussions with secondary students outside of face-to-face meetings. Additionally, classroom teachers are invited to access the same Google Classroom in order to view students’ dialogue. Individual Google Classroom folders feature photographs of lessons with supports and writing or speaking produced by all students in K–12. This transparency allows rapport to be built between ESOL and classroom teachers while also taking out the mystery out of what occurs during sheltered ESOL instructional time.

ILTs utilize district-created quarterly writing assessments to

administer and monitor language acquisition growth. Additionally, ILTs

administer an annual state English language proficiency test in all four

domains (speaking, listening, reading, and writing). ESOL students in

Maryland take the ACCESS for ELLs summative assessment, in addition to

their regular, ongoing assessments, because the ESOL Department is a

member of the WIDA Consortium.

Challenges and Successes

Principals of ILT-serviced schools have reported great

satisfaction having the increased consistency with ESOL services at

their schools. However, having this hybrid (consultant and direct),

itinerant instructional position presents logistical and well as

functional challenges for ILTs.

ILTs discussed several challenges stemming from the nature of

their positions. Locating appropriate instructional space to work with

students was the top issue. Not all schools are able or choose to

dedicate space for ESOL instruction with so few ELLs in their buildings.

Another concern was finding time to collaborate properly with classroom

teachers. Face-to-face collaboration is ideal, yet the timing for

classroom teachers’ planning presents challenges for ILTs to be

available at the same time. Often, collaboration is done through emails,

phone calls, or text messaging, depending on the relationship developed

with each teacher. Though not evaluative in their role, ILTs find they

are able to make suggestions to classroom teachers for improving

instructional lessons that are appropriately scaffolded.

ILTs described some rewarding relationships with classroom

teachers, though many discovered that classroom teachers had little

training in teaching ELLs. Lessons for ESOL students were often not

scaffolded to allow students at varying proficiency levels adequate

access to the English language. The general finding is that teachers

require more training to ensure they are confident in meeting the needs

of their ELLs.

Some of the successes ILTs reported include the joy from establishing rapport with teachers willing to learn best practices teaching ELLs. ILTs learned that they are able to reach a broader population of teachers due to the number of schools in which they work each week. ILTs also enjoy the extended professional opportunity to grow as facilitators; they attend professional conferences and trainings as a result of their hybrid position. Another benefit is the support among team members for each other’s work. Through mentorship and collaborations, ILTs solve issues related to their collective educator practices as well as individual challenges with situations and processes. ILTs found themselves to be enthusiastic learners and collaborators as they began to collaborate across departments and within their own department. For example, ILTs have worked on projects with the International Student Counseling Office, with the Parent Engagement Office, for parent events at schools, and for specific school professional development requests. ILTs spoke about their personal growth in terms of becoming masters at their craft. They attribute their confidence and measurable growth for themselves and their students to their position serving at a variety of school settings and grade levels.

Through effective cooperative planning with organized teams of educators, lesson delivery is truly being differentiated for ELLs. Another benefit from these collaborative teams is providing teacher mentoring and peer coaching. This model is ideal for improving and sustaining teacher retention, which could lead to creating more teacher leaders among faculty at the school level (Dove & Honigsfeld, 2010).

References

Dove, M., & Honigsfeld, A. (2010). ESL coteaching and

collaboration: Opportunities to develop teacher leadership and enhance

student learning. TESOL Journal, 1, 3–22.

Pardini, P. (2006). In one voice: Mainstream and ELL teachers

work side-by-side in the classroom, teaching language through content. Journal of Staff Development, 27(4), 20–25.

Zehr, M. A. (2006). Team-teaching helps close language gap. Education Week, 26(14), 26–29.

Karen Gibson is a Nationally Board Certified Teacher currently working as an ESOL Instructional Lead Teacher in Prince George’s County Public Schools, Maryland. She is passionate about preserving the richness of immigrant stories by encouraging students to write about their journeys. Ms. Gibson facilitates workshops for teachers at national conferences, school districts within and outside of PG County, as well as for pre-service teachers enrolled in university teacher programs.

Kirsten Lennon is a National Board Certified Teacher candidate, currently working as an ESOL Instructional Lead Teacher in Prince George’s County Public Schools, Maryland. In addition to providing instruction for English Language Learners, she facilitates district-wide professional development courses for teachers and provides workshops for international families. She also presents ESOL related topics at international conferences.

Melissa Kochanowski, Ed.D, is the Elementary ESOL Instructional specialist for Prince George’s County. Dr. Kochanowski has experience working as a classroom teacher, ESOL teacher, ESOL coach and ESOL Instructional Specialist. She is passionate about developing teachers and helping them to enhance their skills for teaching their ELLs as well as for collaborating with other teachers.

Kia McDaniel is currently the ESOL Instructional Supervisor for Prince George’s County Public Schools. Prior to her current position, she worked as a classroom teacher, reading specialist, ESOL teacher and specialist.

Sabrina Steward-Salters, M.P.A., is currently an ESOL Instructional Lead Teacher in Prince George’s County Public Schools serving students and teachers at multiple schools in grades K-12. Sabrina spent a summer teaching 2nd grade in Ghana. She has also served as an ESOL teacher at an elementary school in the county. Previously, she served as a K-8 Instructional Coach, ESOL Instructor, Literacy Coach as well as various other classroom positions for D.C. Public Schools.

Tara Theroux is an ESOL Instructional Lead Teacher for Prince George’s County Public Schools. She has been teaching ESOL for 12 years. She currently teaches bilingual students in grades K-12 and also provides instruction to incarcerated bilingual youth. She has also taught ESOL adult education, academic ESOL and higher education ESOL. She has taught ESOL in Russia and Ecuador and facilitated training in Ethiopia.

Sharon Walker has been teaching children and adults for Prince George’s County for more than 15 years. She graduated from The George Washington University in 2004 after completing a double master's degree program in Special Education and English as a Second Language (ESOL). Currently, Mrs. Walker works in the ESOL central office as an Instructional Lead Teacher.

Andrea Worthington-Garcia, National Board Certified Teacher candidate, has been teaching in the field of ESOL for 15 years. She started her career in public schools as a New York City Teaching Fellow in Bronx, NY. Currently, she is an Instructional Lead Teacher based out of the Prince George's County Public Schools ESOL central office. |