|

Elsie Paredes

|

|

Pamela Smart-Smith

|

Education program evaluations are often fraught with contention

and negativity. Attempts at evaluating or analyzing practices can be

seen as an attack on existing staff and current systems. In the same

vein, for the people involved in these evaluations there can be a

propensity to turn what is meant to be a generative and productive

process into one focused solely on the problems, deficits, and

dysfunctions in the educational organization. Reviews and focus groups

become mired in what is and what should be rather than in transformation

and what could be. According to Hammond (1998), the traditional

approach to change is to look for the problem, do a diagnosis, and find a

solution. The primary focus is on what is wrong or broken; because we

look for problems, we find them. By paying attention to problems, we

emphasize and amplify them. Appreciative Inquiry (AI) suggests that we

look for what works in an organization. AI provided us a positive way to

view our current system and to help interrupt the negative spiral that

we perceived was occurring during the annual review process. In an

attempt to change the focus and the tone of our evaluation process, we

decided to try a different approach. What follows is a brief discussion

of our program and how we implemented AI during the annual review

process.

Our intensive English program is a midsized program, Commission

on English Language Accreditation (CEA) accredited, with more than 30

years of experience providing academic English preparation to

international students. Our faculty is mostly composed of eight

full-time instructors and a few adjunct instructors. There are four

administrators involved in our IEP’s management: the IEP director, the

assistant director for academics, the assistant director for faculty

development, and the testing and assessment coordinator. We perform an

annual review of operations (ARO) as part of our regular program

planning and review cycle. Both adjunct and full-time faculty actively

participate in this process, and they all have an opportunity to provide

input and feedback on several areas, such as curriculum, assessment,

student achievement, student services, mission, faculty, facilities and

equipment/supplies, and administrative and student complaints. This

process helps the administration get a better understanding of what is

working and what is not and what can be done to improve. Unfortunately,

this process can quickly turn into a spiral of negativity and a deficit

approach, as we had sometimes experienced through the years. The focus

groups were not particularly focused and targeted problems without ever

coming to a clear consensus on the possible solutions. We began to

research other ways of rethinking how we looked at organizational

problems.

AI, originally developed by Cooperrider (2008), is a “proven

paradigm for accelerating organizational learning and transformation”

(p. 40). AI

provides a way in which evaluators can stop the negative spiral and

generate new and positive ideas. It focuses on appreciating what is and

seeks to move to what could be by using the process of personal or

intraorganizational narrative and inquiry. As a process, it begins by

identifying the “positive core and connecting to it in ways that

heighten energy, sharpen vision, and inspire action for change” (Cockell

& McArthur-Blair, 2012, p. 13). Since AI was first developed,

there have been many different iterations and applications to different

public and private sector fields. After careful research, we chose the

model developed by Hammond (2013) upon which to base our own

implementation. Hammond’s model lists five stages of the process, which

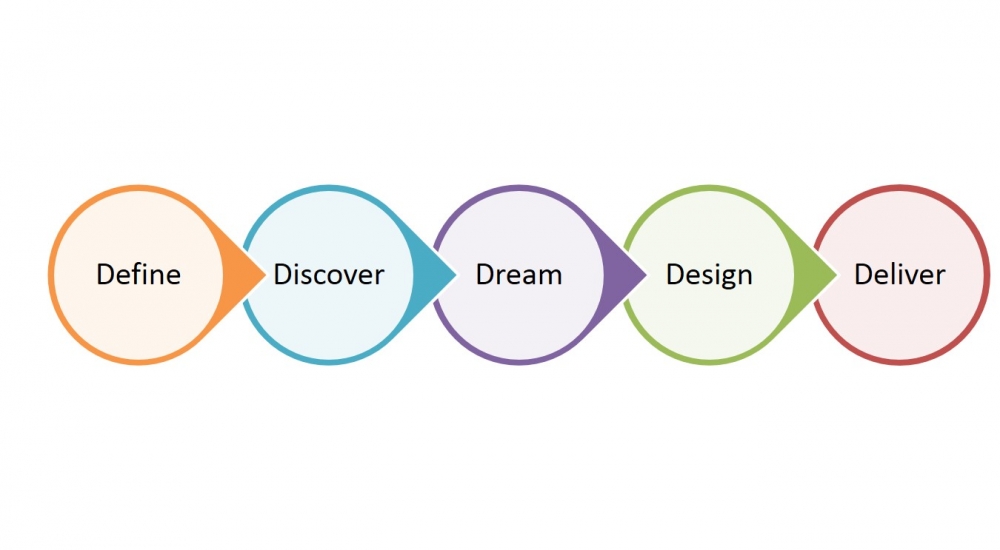

are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1. 5-D model visual and explanation. Hammond (1998).

A brief definition of the five stages is as follows:

-

Define: consists of clarifying the

direction the key intention for the evolution of the team or

organization. Instead of asking, “What is the problem to be solved?”,

the key questions are “What do we want more of? What is our best

aspiration?”

-

Discover: enables us to operate from the

assumption that what we want more of already exists in the system.

-

Dream: enables us to create an embodied representation of the desired state.

-

Design: invites us to create the overall

architecture of the desired state and to determine which aspects are the

most important to implement change.

-

Deliver: enables us to choose the actions

to move toward the future in the most sustainable way.

The implementation of AI at our institute took place when we

conducted our program’s ARO. Data were collected by the three IEP sites

in two ways: surveys and focus groups. Using SurveyMonkey, an online

survey was created by members of the Joint Curriculum Committee based on

the revised and edited questions of the previous year’s ARO.

Instructors were asked to complete the anonymous online survey. Once the

survey process was completed, the sites met individually to code the

data and to identify key areas for further exploration by the

instructors. Using the questions and results, focus groups led by

full-time faculty were conducted during a staff meeting. Though it would

have been ideal to have outside moderators and note-takers for the

focus groups, we faced monetary and time constraints that made having

outside leaders not feasible. Instead, we provided training to both the

moderators and the note-takers explaining the philosophy, process, and

application of AI during the focus groups. We made sure that they were

comfortable with the new paradigm required. Moderators were given

tactics to help refocus discussions if needed. In the focus groups,

instructors were given areas to discuss (mission; curriculum; student

achievement; faculty; facilities, equipment, and supplies;

administrative issues; and student complaints). The sessions lasted

approximately 2 hours. Each group recorded its responses in a written

format. The groups reconvened into one large group to share their

results, provide additional feedback, and ensure that there was a

general consensus for the prioritized items. All notes were then sent

out a few days later to the focus groups for member checking. The

minutes were then provided to the associate and assistant directors for

compilation and analysis. Once all the data were collected and analyzed,

the IEP academics team met with the Joint Curriculum Committee to

discuss any common themes among the three sites. An implementation plan

and timeline was also created and shared.

Overall, the implementation of AI in the focus groups was a

positive experience. Faculty and staff that took part in the ARO shared

that, compared to our previous program evaluation method, AI gave them

more of an opportunity to discuss common concerns in an open manner,

gave them a better perspective and focus, and provided a more

constructive and positive environment. The participants felt that it

would be good to continue and refine that process for future focus

groups. As part of the process, we also conducted an anonymous exit

survey. Comments included: “More constructive good ideas were brought

up”; “Focus is the key word. We have a chance to put things in

perspective”; and “It is very helpful to start with what works.”

Suggestions for next time were to allow the instructors to see the

entire survey as they had in the past to help improve transparency. This

change was made in subsequent years as a result of instructor feedback.

The process of AI does require more intentionality than most

traditional program review methods in how questions and discussions are

framed. Being able to ask effective questions helps participants not

only to focus on the positive, but to think critically about what could

be improved. The purpose of AI is not to view everything through

proverbial rose-colored glasses, but to build upon what works. While AI

does take more time to set up and implement, the approach engages

participants to critically analyze and innovate new solutions rather

than remain mired in a pool of negative thought. As a result of our

trial with AI, we have decided not only to implement the process in

focus groups, but to also apply AI in other areas dealing with faculty

input, feedback, and development. Overall, AI helped with instructor

buy-in, helped generate new ideas, and made the annual review process

less painful and less fraught with negativity.

References

Cockell, J., & McArthur-Blair, J. (2012). Appreciative Inquiry in higher education: A transformative

force. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Cooperrider, D. (2008). The Appreciative Inquiry

handbook: For leaders of change. Oakland, CA:

Berrett-Koehler.

Hammond, S. (1998). The thin book of Appreciative

Inquiry (2nd ed.). Bend, OR: Thin Book Publishing Company.

Hammond, S. 2013 (3rd ed.). The Thin Book of Appreciative Inquiry: Bend, OR: Thin Book Publishing Company.

Elsie Paredes is the IEP director and associate

director at the Virginia Tech Language and Culture Institute, where she

directs and manages the intensive English program.

Pamela Smart-Smith is the assistant director for

academics at the Language and Culture Institute at Virginia Tech. She is

currently working on a PhD at Virginia Tech with a focus on ESL and

multicultural education. |