|

In a recent Atlantic Monthly article excerpt of his new book Pinches: How the Great Recession Has Narrowed Our Futures & What We Can Do About It, features editor Don Peck (2011) advises that in the current U.S. plutonomy, the job market may prefer individuals with higher education from selective universities, a history of civic engagement and stable personal life, and “creative, analytic, and interpersonal skills” (p. 65). Students who cultivate these traits may be better positioned to participate in a faster rate of innovation and research and development (R&D) – two main keys for economic growth and socio-cultural stability.

Within the climate of the U.S. Great Recession, do you need to cultivate analytical or research writing skills in your students? Do you lament any uncivil language that your students pick up and worry about how it may affect their employment opportunities? I do. Thus, the current article presents a lesson that I developed on primary research writing which aims at cultivating creative, analytic, and interpersonal skills to help students poise themselves for research assistantships and a people-skills-based, R&D job market. The lesson uses “civility” as the theme and language samples from two historical pragmatics studies and a period film as the linguistic data for analysis. It includes the activities of building context, raising awareness of discourse features, comparing discourse features, transcription, reporting on sociolinguistic variables, and conclusions. The sequence of activities (described in Parts I and II below) is intended to mirror the sections of a scholarly research article.

A LESSON FOR PRIMARY RESEARCH WRITING USING HISTORICAL PRAGMATICS AND PERIOD FILM

Context of the Lesson

Using the research methods of discourse or conversation analysis, the principles of pragmatics, and descriptive statistics, I developed this lesson for a two-semester college writing course. The lesson was used in the last month of the first semester after the students had completed two major writing assignments, namely a basic argument essay and a text analysis essay. Teachers might use this lesson after students have control of the basic structure of an argument essay and the information structures of academic paragraphs (i.e., a body paragraph, introduction, conclusion). There were about 12 students in each section for a total of about 24 students (maximum enrollment per section = 15). Because of small class sizes and student support services, each student had ready access to a relatively broad range of individualized academic support. All students were in their first semester of college study, and they had a range of different majors in math, engineering, social sciences, and natural sciences. They were also a mix of international and U.S. students with a range of different L1s and cultural backgrounds. Many if not most of the students were multilingual and multicultural. I invited students to do Part I in class and Part II as homework. For Part I, I first asked students to write down their answers (i.e., free-write or brainstorm). Then, I invited students to share their answers verbally as part of a class discussion. As students shared their answers, I echoed them and, if necessary, re-phrased their responses in formal, academic discourse. Teachers could write relevant phrases on the board so that students could see how their ideas look in formal academic language. Also, I asked probing questions aimed at critical thinking and raising awareness of different ways of thinking. For example, some female students expressed that boys who address them in a civil manner are viewed as “weird.” An alternative way of thinking is to see this kind of language as respect. For Part II, students could work in small groups of two or three if they wished to reduce the amount of time it took to transcribe and code the data. This is a usual practice in research writing. The only challenge with the lesson was the accessibility of the film (note: two copies were made available in the university library, and students were regularly asked about their progress). To ensure access to the film, students were given 30 days to complete the activities (which were provided as an electronic document) and post their findings to a forum on Moodle. The Moodle forum allowed students to read each other’s work and was intended to resemble the act of publishing one’s research. Alternatively, some universities have technology that allows students to access films via portals. Naturally, other Internet-based software, activities, or student publications may serve as venues to simulate academic publishing.

Learning Objective

To identify, transcribe, classify, and quantify language items (e.g., key phrases, vocabulary or lexical units, grammar or structural units) that encode civility or incivility; to draw inferences through comparisons between quantitative data and communicative contexts; to experience firsthand some of the processes associated with primary research and research writing; and to use academic language appropriately.

Part I (25 points)

A. Writing Activity 1: Building Context (5 points). Civility may be a higher priority in some social domains (e.g., education, the family home) than it is in others, and it may not be manifested when expected. Also, the language of civility, and the intentions of the speaker, may not always be recognized by listeners. Consequently, it can be useful to study the language of civility to raise one’s awareness. Have you ever encountered uncivil discourse? Can you describe the language used? In your opinion, should civility be a priority? If so, what should it look like in language, body language, or space between speakers? Activities 2-5 below are aimed at raising awareness of civil vs. uncivil discourse across time periods and social domains.

Note to teachers: Activity 1 is intended to build context which is the first step in the SIOP method (Echevarría, Vogt, & Short, 2008). The SIOP method recognizes that students approach the same topic and task from different background experiences. So, the building context activity is aimed at establishing a shared background for each student in the class. Also, it offers an opportunity to pre-teach any vocabulary or cultural knowledge that may be necessary to ensure student success. Teachers may note that there is no “correct answer” per se to the activities in the lesson, and students may change their thinking throughout the lesson. Student answers to each activity will vary, and the main role of the teacher is to organize the students’ ideas into a clear, organized class discourse. Additionally, since the goal of the lesson is to give students experience with primary research, teachers may invite students to share their perceptions of the research and discovery process, for example: What do you enjoy about research and discovery? How might you use this process in your other classes or on the job? Furthermore, the activities encourage students to operationalize “civility” and “incivility” deductively. Since I used these activities as an introduction to research writing as part of college writing, not a research methods course, I omitted explicit discussion of operationalization. However, teachers may keep it mind and touch on it in Activity 3 or 4. B. Writing Activity 2: Raising Awareness of Discourse Features (10 points). The samples of civil discourse below were extracted from 18th-century British personal letters in which the author of a lower social class addresses a patron of a higher social class (Fitzmaurice, 2002; 2003) (note: the original 18th-century spelling is retained in order to help facilitate students’ awareness of change in language over time). Examine the sentences below, and make a list of the words or phrases that, in your opinion, suggest civility. Also, underline words or phrases that seem different from Present-Day English (PDE).

- I should be extreamly glad of an opportunity of deserving it and am therefore very ready to close with the proposal that is there made in of accompanying My Lord Marquess of Hertford in his Travails and doing his Lordship all the services that I am capable of. (Joseph Addison to Charles Seymour, Duke of Somerset, 1703).

- I must desire you will be so kind as to give orders for any thing that may be necessary to make my Lodgings Inhabitable. (Joseph Addison to Joshua Dawson, Letter 160).

- I am very much obliged to you for your friendship in Collins's affair and question not but I shall hear from you as soon as it is finished. I must desire you to deliver my Lord Whartons commission into Mr. Harrisons hands who will transmitt it to him, when he has an opportunity. (Joseph Addison to Joshua Dawson).

- Opening Salutation: Your Lordship having given me leave to acquaint you with the names and pretensions of persons who are importunate with me to speak to your Lordship in their behalf I shall make use of that Liberty when I believe it may be of use to your Lordship or when I can not possibly resist the solicitation. (Joseph Addison to Charles Montagu, Earl of Halifax, 1 Oct. 1714).

Examine your list of words or phrases; can you write some “rules” or guidelines for civil language during this time period? From these examples, can you guess what purpose the language of civility fulfilled in 18th-century British society? In your opinion, how has English or the expression of civility changed since the 18th century?

Note to teachers: The most important aspect of these excerpts is the modal verbs, and so teachers may focus on this if their students are equipped to do so. Some teachers may wonder how students respond to the 18th-century language. When I used this activity, I simply asked students if they noticed anything different about the English, if they could tell who had the higher social status, or if they would ever use an opening salutation like that of Item #4 (either in English or their L1). Students agreed that English has changed, and it is fun and interesting to note how languages change over time. An advantage of looking at historical samples is that it seems to heighten students’ awareness of language features. At first, my students thought the excerpts were difficult to understand, but then the samples piqued their curiosity and inspired them to be on the lookout for language features that are associated with particular functions. Also, I explained that the goal was not necessarily to understand the excerpts thoroughly but to develop an eye for objective observation. Furthermore, one of the authors, Joseph Addison, was part of a cohort of six British writers (e.g., Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, William Congreve) who were quite prolific and produced, some say, the best literature in the English language. This impresses some students. Thus, either before or after Activity 2, teachers may wish to point this out and perhaps draw on these authors for extension activities such as those described in McKay (2001).

C. Writing Activity 3: Comparing Discourse Features (10 points). The lines of civil and uncivil discourse below were transcribed from the period film Possession (2002). This film is based on the novel by A. S. Byatt and portrays academic and romantic relations in two time periods: 19th-century and contemporary England. Examine the 16 utterances below, and either make a list, underline, or highlight the words or phrases that, in your opinion, suggest civility and incivility. The first four lines have been done as an example, with civil discourse highlighted in orange and uncivil discourse highlighted in blue. Next, can you write some “rules” or guidelines for civil vs. uncivil language during the 19th century and the 21st century? Also, the discourse in film tends to be exaggerated because the director and actors have limited time to get their point across. So, based on your experiences, are these lines realistic or unrealistic? Why or why not?

Note to teachers: In my experience, adult ESL learners find movie sub-titles useful for language learning, particularly the language of politeness. Also, I provided these activities as an electronic document so that students could “code” the lines (i.e., highlight text or change the font color) on their laptops. In the film comments, the director explains that the film parodies present-day academia and romantic attachments: Hypothetically, one expects such speakers to be civil or polite with each other, but in reality, the speakers are uncivil. Thus, the film offers social criticism and points out how society has declined in some ways since the 19th century. When I used this activity, the students found the 21st-century lines realistic, and while the 19th-century lines were too expressive for today, the general idea of civility is valuable. The story line of the film also inspired discussion, and teachers may note that the 19th-century couple involves bisexuality, infidelity, and illegitimacy while the 21st-century characters are involved in romance with a colleague, national stereotyping, grave robbing, and classism. Either before or during the activity, teachers may point out dialect differences between British and American English. As extension activities, teachers may draw on cinematography and invite students to note the body language of the actors or the color schemes of the movie sets and actor wardrobes – namely, the role of cool colors (e.g., blue-grey) for incivility vs. warm colors (e.g., tan) for civility. Below is the URL for the movie’s official web site where stills and downloads are available.

[http://www.possession-movie.com/main.html]

- Dr. Fergus Wolfe to Dr. Roland Michell: “Keeper of Ellen’s flame, that’s bottom of the food chain, old sport. Well, ‘publish or perish,’ as they say, or in your case, ‘perish or perish’.”

- Dr. Maude Bailey to Dr. Roland Michell: “Did you not do any reading before you came? I mean, you don’t know the first thing about her, and yet you make these leaps.” (Note: Dr. Michell did in fact do some reading; so, this discourse is uncivil because Dr. Bailey is imposing inaccurate assumptions.)

- Mr. Randolph Henry Ash to Ms. Christabel LaMotte: “I shan’t forget the first glimpse of your form, illuminated as it was by flashes of sunlight. I have dreamt nightly of your face and walked the landscape of my life with the rhythms of your writing ringing in my ears.” (Note: A distinction can be made here between the romantic discourse in the first sentence and the civil discourse which is highlighted in orange.)

- Ms. Christabel LaMotte to Mr. Randolph Henry Ash: “I shall never forget our shining progress towards one another. Never have I felt such a concentration of my entire being. I cannot let you burn me up, nor can I resist you. No mere human can stand in a fire and not be consumed.”

- “The highest pleasure [to meet you].”

- “Who are you? Oh, you’re that American who’s over here.”

- “It was a great pleasure to talk to you at dear Crabb-Robinson’s party. May I hope that you too enjoyed our talk. And may I have the pleasure of calling on you.”

- “I’m sorry, I don’t [remember you]. [You have a] nice [woman’s] coat, though. [man to man, academics]

- “I was entranced and moved by your brief portrait of your father.”

- “Yes, well, it [your investigation of the potential correspondence between these two historical figures] seems like a bit of a wild goose chase to me.”

- “Perhaps I am wrong to disturb you at this time with unseasonable memories, but I find I have, after all, a thing which I must tell you.”

- “I think of you again with clear love. Did you not flame and I catch fire? Was the love that we found not worth the tempest that it brewed? I feel it was. I know it was.”

- “I guess I’ll just uh… hell, I don’t know – go look up shit on the microfiche [and] suffer over you.”

- “Well, I won’t tell you you’re amazing looking then. You’re probably sick of hearing it.”

- “He’s American, for God’s sake. He’s probably off trafficking drugs.”

- “Yes, well, unfortunately they didn’t have video cameras in those days [to record female lovers], so you’re out of luck.”

Part II (25 points)

D. Activity 4: Transcription (10 points). Using the examples from Part I as a examples of civil and uncivil discourse, identify the manifestations of civil and uncivil discourse in the film Possession (2002). Transcribe the manifestations of civil and uncivil discourse in two 5-minute segments of the film (one segment for each time period) or the whole film if you like a challenge (tip: watch the DVD with the subtitles turned on). Code the discourse samples from your segments according to these variables (tip: use different font or highlight colors): (a) time period (Victorian or Present Day English); (b) social role (strangers, colleagues, lovers); and (c) sex (female to female; male to male; female to male; male to female). Tally the counts for each variable.

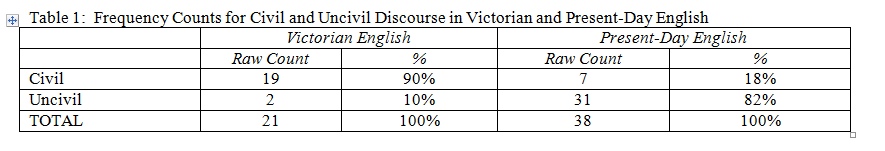

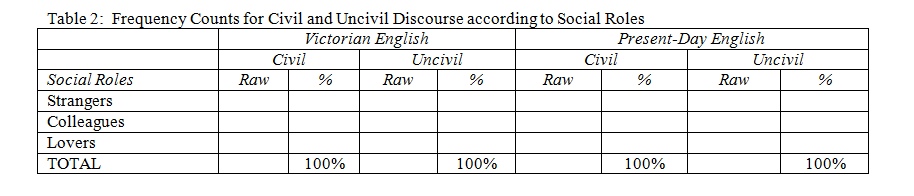

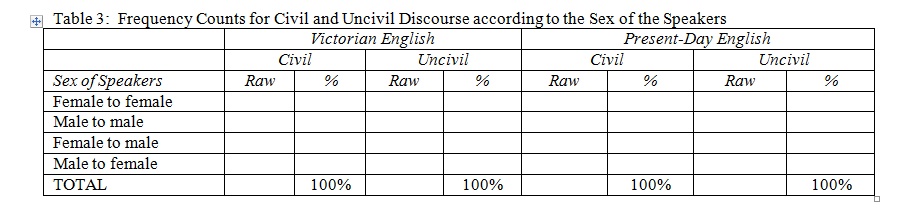

Note to teachers: The 16 utterances above are roughly half of the civil/uncivil utterances for the film. Depending on the level of the course, teachers may wish to work only with this set of 16 utterances or invite students to transcribe portions of the film that either they or the students select. Teachers may note that this activity is not traditional transcription, and students may take screen shots of the subtitles or use other resources to copy the film’s dialog. When I used this activity, the students were told that the 16 utterances were from roughly the first half of the film, and they transcribed the second half. Later, students commented that it was easy but time consuming. I believe this is an important aspect of research for students to experience and understand. Also, a few expressed concern about finding more or fewer utterances than I did. For me, this was not an issue because the goal was for students to experience data preparation. So, this activity gives students an authentic experience in primary research; however, teachers should adjust the length of the transcription activity so that it is suitable for their class (e.g., the 16 lines only; 16 lines + two 5-minute segments; or 16 lines and rest of the film). E. Activity 5: Reporting on Sociolinguistic Variables (10 points). Use the frequency counts from Activity 4 to fill in Tables 2 and 3 below, and calculate the proportions (tip: to get the proportion, divide the raw count by the total; include the percentage symbol after the number to show that it is a proportion). Table 1has been completed as a model. Under each table, discuss and illustrate the findings (tip: you can watch the DVD with the director’s comments turned on to gain insight on the intention behind the actors’ lines).

Discussion for Table 1: Does the time period seem to make a difference in the use of civility? List 2-3 illustrations for each time period. Are there any noteworthy language features that distinguish the two time periods (e.g., words, phrases, grammatical structures)?

Note to teachers: If students do not choose the same segments of the film, then the frequency counts will vary. Actually, even if students choose the same segments or transcribe the whole film, there will be some variation in the frequency counts since students may identify and/or count utterances differently. However, the proportional distributions should be similar. This variation can be a point of discussion, and teachers may discuss inter-rater reliability if their students are ready for this conversation. Since I did this activity as part of college writing, not a research methods course, I acknowledged that variation happens, and in a serious study, we would take steps to ensure reliability in the coding procedure. In addition, for Activities 5-6, I have used the term “language features” in an effort to be generic. I recognize that some teachers may use grammar terms from various grammatical approaches while other teachers may use a lexical approach or avoid linguistic terminology altogether. So, teachers should feel welcome to adjust the wording to fit how they teach and what their students are equipped to do. When I used these activities, I did not teach any grammar terms. Instead, I asked students what they noticed, the students used their own ways of identifying language patterns, and I followed their lead. If students asked me for linguistic terminology, I provided it. This is suitable since the goal of the lesson is to experience primary research and research writing. Furthermore, as Table 1 suggests, the language patterns are quite pronounced. So, for example, it is easy to see that the Victorian period manifests more civil utterances than present-day society. The movie dialog is relatively easy to observe, and the trends for Tables 1-3 are fairly pronounced which helps ensure a successful experience for each student.

Discussion for Table 2: Does the social role of the speakers seem to make a difference in the use of civility? List illustrations for each social variable. Are there any noteworthy language features that distinguish the social roles (e.g., words, phrases, grammatical structures)?

Discussion for Table 3: Does the sex of the speakers seem to make a difference in the use of civility? List illustrations for each sex. Are there any noteworthy language features that distinguish the interaction between speakers of the same or different sex (e.g., words, phrases, grammatical structures)?

F. Activity 6: Conclusion (5 points). What recommendations can you make for society today? If speakers wanted to be more civil in their interactions, what kind of language should they strive to integrate? Which language features should speakers avoid if they do not want to be perceived as uncivil? Should speakers vary their language according to the social role or the sex of the listener? If so, how?

Note to teachers: This series of activities and the conclusion section yielded a much wider range of values from students than I anticipated. Some concluded that civility is important and needs to increase. In contrast, others argued that incivility plays an important role in society where self-preservation is concerned. These students pointed out that incivility is a strategy to protect oneself from being exploited. In general, although students completed the analysis activities with ease, their recommendations for society varied widely which made the project both interesting and enlightening. When I used these activities, I provided students with an electronic document of the activities which served as a worksheet. Teachers may wish to invite students to write up the document as a research paper or article.

CONCLUSION

Historical letters offer an opportunity to observe the role of civility at a time when English society was organized according to a social hierarchy. The period film Possession (2002) compares human relations in English society in the 18th versus 21st centuries, and thereby suggests the dissipation of professional and romantic relationships over time. In addition, it illustrates the discourse in which these social ties are manifested, and this serves as sociolinguistic data which may be used to organize a comparative discourse analysis and research writing assignment for learners. In addition to teaching skills for systematic analysis and analytical writing, such a lesson can provide students with an opportunity to discover how a language may change over time (Aitchison, 2008). Also, it may raise awareness of a language’s capacity for register variation (Ure, 1982; Biber & Conrad, 2009), which occurs in response to the communication needs for particular situations. Moreover, it may highlight the need to consider language choices and linguistic layers of meaning (Thomas, 1998) in personal and professional communication.

REFERENCES

Aitchison, J. (2008). Language change: Progress or decay? (3rd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Biber, D. & Conrad, S. (2009). Register, genre, and style. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Echevarría, J., Vogt, M. E., & D. J. Short. (2008). Making content comprehensible for English language learners: The SIOP Model. New York, NY: Pearson Education.

Fitzmaurice, S. (2003). The grammar of stance in early eighteenth-century English epistolary language. In P. Leistyna & C. F. Meyer (Eds.), Corpus Analysis: Language Structure and Language Use, pp. 107-132. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Rodopi.

Fitzmaurice, S. (2002). Politeness and modal meaning in the construction of humiliative discourse in an early eighteenth-century network of patron-client relationships. English Language and Linguistics, 6(2), 239-265.

LaButte, N. (Director). (2002). Possession [Motion picture/DVD]. United States: Warner Bros.

McKay, S. L. (2001). Literature as content for ESL. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed.), pp. 319-332. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Peck, D. (2011). Can the middle class be saved? The Atlantic, 308(2), 60-78.

Thomas, J. (1998). Meaning in interaction: An introduction to pragmatics. Harlow, England: Longman.

Ure, J. (1982). Introduction: Approaches to the study of register range. International Journal of the Study of Sociology, 35, 5-23.

Catherine Smith has a Ph.D. in applied linguistics from Northern Arizona University with preparation in descriptive grammar, pragmatics, discourse analysis, and corpus linguistics. Her research addresses register variation with applications in writing education and teacher or teaching assistant development. Currently, she is a lecturer in the Division of the Humanities at the University of Minnesota, Morris. |