|

Students often struggle with argumentative writing assignments

because concepts such as argument, counterargument, and rebuttal may be

new to them. Dialogue writing can serve as an entry point for students

beginning argumentative writing. This teaching technique takes advantage

of various online tools for dialogue writing, such as a class

discussion board and online digital storytelling tools. Through the

incorporation of sound classroom instruction and the use of technology,

students will not only gain a clearer understanding of how to structure

an argument but also be able to share their dialogues and receive

feedback from others. In this article, I first explore the pedagogical

basis for dialogue writing and then explain the process for creating

online dialogues.

Dialogue writing is a useful technique for introducing students

to the basic concepts of argumentative writing, such as argument and

counterargument. According to Neman (1995) in Teaching Students

to Write, “Students need to put themselves in their readers’

shoes and anticipate their response. In trying to think as their readers

might think, they should be able to anticipate their questions and

supply answers, to foresee their objections and quiet them” (p. 204).

Because it is important for the writer to consider multiple perspectives

and to anticipate possible counterarguments and alternative ways of

thinking, this step is essential. The benefits of dialogue writing are

outlined in Bean’s Engaging Ideas (2001):

These assignments (dialogues or argumentative scripts) allow

students to role-play opposing views without having to commit themselves

to a final thesis. The freedom from traditional thesis-governed form,

as well as the necessity to role-play each of the opposing views in the

conversation, often stimulates more complex thinking than traditional

argumentative papers, in which students often try to reach closure too

quickly. By preventing closure, this format promotes in-depth

exploration. (p. 129)

Writing online dialogues would fit neatly into an introductory

unit on argumentative writing at the paragraph or essay level. I used

this teaching technique in a first-year paragraph writing course at a

Japanese university that meets twice a week for 90 minutes, including

one session in the computer lab. The class carried out this project over

the course of four class periods, but the amount of time required would

vary depending on the students’ level and the amount of work done

outside of class. After the teacher introduces the basics of

argumentative writing and the dialogue writing assignment, students

decide on a controversial issue to write about. For example, students

may wish to write a dialogue between two people exploring various

opinions about smoking in public places. In addition, students could

take on an issue of concern at their school, such as the access to

technology, quality of the food in the cafeteria, or course offerings.

After students have chosen a topic, they are ready to begin

brainstorming multiple perspectives. Students could brainstorm

individually; also, they could post their topic on the class discussion

board, and students help each other come up with reasons for and against

their position. Throughout the brainstorming process, students can be

encouraged to think of as many points of view as possible, including

majority as well as minority viewpoints, or views from various

stakeholders in the issue. By involving the class in the brainstorming

process, students can access a wider variety of points of view and

appreciate the value of discussion and collaborative brainstorming. In

addition, students tend to participate actively when brainstorming

activities are conducted via discussion board. Because of the

asynchronous discussion, students have more time to consider and

formulate ideas and, consequently, students may naturally offer

arguments, counterarguments, and refutations—points that can be

highlighted by the teacher.

After brainstorming ideas, students can compile the list of

reasons they collected and add any other ideas they may have. From this

list, students choose the viewpoints they would like to include in their

dialogue; these will be the basis for the project they will create

using an online digital storytelling tool (such as Dvolver,

which allows users to choose from a variety of characters, scenes, and

backgrounds. The interface is user friendly, so students familiarize

themselves with it quite easily; however, it is important to note that

the character’s utterances are limited to 100 characters per line,

although each character can speak several times in a maximum of three

scenes. The process for creating a movie in Dvolver is relatively

straightforward and most students don’t have much difficulty using the

Web site. First, the user should select a background, characters, and

type of scene, then type in the dialogue and choose background music.

The process can be repeated to add scenes to the movie.

Depending on the level of the students, the teacher may

introduce the online tool and have them start creating their dialogues

right away; however, storyboarding, or planning out the dialogue, will

give them more of a chance to think more carefully. In addition, because

Dvolver does not have an edit function, once a story is created, it

cannot be changed; therefore, it behooves the students to already have

an idea and draft. As recommended in “Cartoon Festival: An International

Digital Storytelling Project,” when the educators used Dvolver with

their students, they had students prepare scripts on a wiki that could

be proofread, edited, and revised collaboratively (Hillis, et al.,

2008). If the class is not using a wiki, these scripts could easily be

posted on the class discussion board or typed in Microsoft Word or

Google documents. After the storyboards or scripts are complete, the

students are ready to prepare their dialogues with Dvolver.

Although the Dvolver characters can seem humorous, students

have created thoughtful dialogues on important issues. For example, see

this instructor-made sample

dialogue on the issue of school uniforms. In addition, the

following dialogues were made by students in a first-year

paragraph-level writing class in Japan: "Living by

Themselves" and “Debate about

Smoking.”

After creating the movie, students can e-mail the movie to

themselves and to the instructor. The movie will have its own URL and an

html code that can be embedded elsewhere, such as on a class blog;

alternatively, the links to movies can be posted on a discussion board.

Comments can be left directly at the Dvolver site or in follow-up posts

on the class discussion board. Encouraging students to comment on each

other’s movies/dialogues is a productive way of exposing the class to a

variety of issues and opinions in a fun and engaging manner; also,

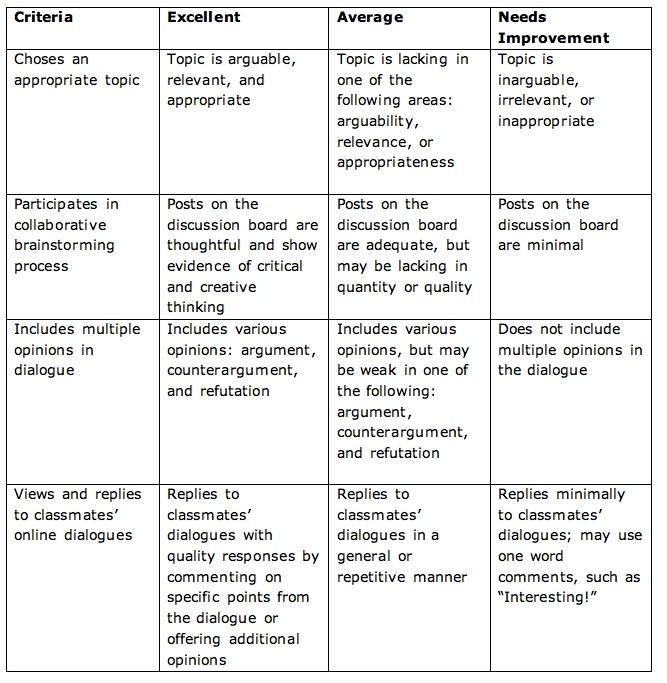

students like to receive feedback from others. In order to assess

students’ work, the instructor can construct a rubric, such as the

following.

After brainstorming all sides of the issue and creating the

dialogues with a digital storytelling tool, students should feel more

comfortable with the concepts of argument, counterargument, and

refutation. Unlike performing dialogues in class, the artifacts and

comments that students generate online can be reviewed as many times as

students would like, and the dialogues can be saved for use in future

courses. Of course, the assignment can be taken one step further, and

students can draft formal argumentative essays on their topics.

Throughout the writing process, students are actively engaged in the

learning. In fact, as Hillocks (2010) stated in “Teaching Argument for

Critical Thinking: An Introduction,” for students to be able to

construct solid arguments, “they will have to become engaged in a highly

interesting activity that is both simple and challenging, for which

feedback is immediate and clear, that allows for success and inspires

further effort” (p. 27). Combining rich classroom-learning experiences

with online tools will help students gain an introduction to

argumentative writing skills.

REFERENCES

Bean, J. C. (2001). Engaging ideas: The professor’s

guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in

the classroom. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass

Publishers.

Hillis, M., da Silva, J. A., & Raguseo, C. (2008).

Cartoon festival: An international digital storytelling project. TESL-EJ, 12(2). Retrieved from http://tesl-ej.org/ej46/int.html

Hillocks, G., Jr. (2010). Teaching argument for critical

thinking and writing: An introduction. English Journal,

99(6), 24-42. Retrieved from http://www.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/EJ0996Focus.pdf

Neman, B. S. (1995). Teaching students to

write (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University

Press.

Mary Hillis, maryehillis@yahoo.com,

is an assistant professor of TEFL at Kansai Gaidai University in Japan.

She completed her MA TESL at Bowling Green State University and her

professional interests include writing pedagogy and online professional

development. |