|

To some teachers, assessing compositions (i.e., providing

error correction or/and written commentary) may be considered as a chore

or dirty job because it may neither benefit low-achieving students’

writing nor facilitate effective feedback practices (Belanoff, 1991, p.

61). Owing to unproductive marking techniques, teachers are likely to

turn into “composition slaves” while students may become unmotivated to

learn writing (Hairston, 1986). Provision of constructive feedback for

successful revision is thus crucial in enhancing student learning

outcomes as well as encouraging learner independence in writing.

In the literature, utilizing feedback-by-marks (e.g., 68/100 or

B- at the bottom of a paper) or feedback-by-comments (e.g., “need to

rework the overgeneralization of the claim made in the second

paragraph”) in assessment of writing has been debated, although

students, teachers, and parents typically prefer the former (Lee, 2007,

p. 203). Some scholars argue that feedback-by-marks primarily promotes

performance, not learning and comparison of students’ abilities (Black

et al., 2003). Although feedback-by-marks may motivate students to focus

on performance in the assessment of writing,

particularly of high achievers, feedback-by-comments can shift their

attention to text improvement through error feedback (line-by-line

editing) and written commentary (qualitative feedback that suggests

discourse-related revisions).

Comment-only marking (COM), promoted by the Assessment Reform

Group (2002), refers to (a) feedback given to students in the form of

written commentary rather than marks/scores or (b) temporary suspension

of grades in order to draw students’ attention to the formative feedback

from teachers. While there are studies that support regular use of

feedback-by-comments or COM in writing (Huot, 2002), research into its

potential in enhancing students’ learning of writing, particularly in an

EFL pre-university setting such as Hong Kong, remains inadequate. To

gain a deeper theoretical understanding of COM, I adopt an action

research approach to find out students’ reaction to COM in a

portfolio-based writing course.

CONTEXT

The study took place in a two-year associate degree course at

one university in Hong Kong that offers programs in various subject

disciplines such as social studies, languages, and psychology. Data were

collected from a foundation writing course offered in Year 1, Semester

2. The course adopted the portfolio approach wherein students were

expected to engage in multi-drafting and reflection upon different

entries. Each portfolio was holistically read and graded by the

researcher and the other rater at the end of semester. The 31

participants were aged between 17 and 19 at the time of the study, and

were mostly Form 5 (Grade 11) school leavers.

PUTTING COM INTO PRACTICE

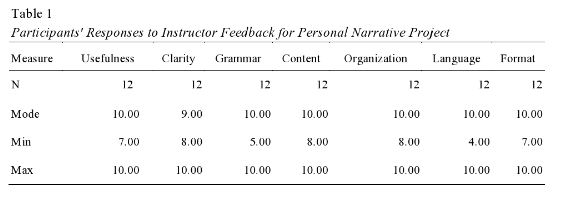

In lieu of a letter grade and evaluative comments (i.e., “well

done” or “poor work”), COM was presented to students by four types of

teacher written feedback including (1) clarification, (2) explanation,

(3) suggestion, and (4) error correction. Instances of these feedback

types are illustrated in Table 1.

In addition, COM was carried out in four consecutive phases.

The first stage was a 2-hour induction program, familiarizing students

with the aims, benefits, and rationale of using COM in the writing

course. The second was a 3-hour training session that gave students

guidance on how to act upon teacher written commentary on such topics as

content errors related to ideas, logic, and coherence. The session also

included discussion about assessment criteria, explanation of types of

annotated commentary, demonstration of text revisions, and application

of incorporating teacher written feedback into revisions. Hands-on

practices of responding to COM (i.e., class time specifically allocated

for students to act upon teacher written feedback), which took place at

the third week of each writing cycle (5 throughout the 15-week

semester), formed the next phase of implementation. The last procedure

was a debriefing that helped students review whether learning targets

were met and whether writing improvement was made at the end of the

course.

METHOD

Research data included a student focus-group interview

(n = 8), field notes, analysis of revision changes

(n = 8; 48 texts, 16 original, and 32 revised)

(Faigley & Witte, 1981), and a text-based interview (from

another portfolio reader). The interview data were transcribed and

analyzed into relevant categories. Field notes were then coded based

upon the same set of categories identified from the interview data.

Students’ revision changes in multiple drafts were analyzed by me and a

colleague who was teaching in the same course to enhance the accuracy of

text analysis.

The research questions and manner of addressing them included the following:

(1) The interview and textual data addressed the ways in which

COM benefited or impeded students’ learning of writing (i.e., rhetorical

choices and writing mechanics).

(2) Analysis of text revisions, accompanied by the text-based

interview, examined whether COM had an impact on student writing

development.

FINDINGS

Benefits of COM

When asked about the effectiveness of COM, five students felt

that feedback from the current author was constructive for text revision

and made them develop an awareness of how certain “problems” of writing

(i.e., register) could be improved. One of them said that COM made her

feel less stressed to rework the compositions, since she used to get a

low grade (e.g., a failing grade) with criticism such as “poor grammar”

from the teacher. Another student also revealed that COM promoted

learner autonomy in writing because it required greater student

involvement in the writing process (i.e., incorporating feedback into

subsequent revisions). One student explained how he revised the drafts

with teacher feedback: “I often rephrase inappropriate expressions and

elaborate incomplete ideas in my drafts after receiving the instructor

feedback.”

Impediments of COM

Despite its benefits, three students remarked that COM had its

limitations when applied in the Hong Kong classroom. One of them argued

that he was overwhelmed by lots of qualitative feedback to which he did

not know how to respond (e.g., “this paragraph is packed with too many

irrelevant examples, and contains over-stated claims without the support

of evidence”). Another two students reported that although feedback

from COM was beneficial to text revision, it did not explicitly inform

their standards of writing. One student found that the problem with COM

was her inability to revise the discourse-related aspects of writing,

such as coherence, because most feedback from me emphasized written

commentary (e.g., “be aware of the continuity in idea development by

using the same theme in each sentence”) rather than error correction.

COM and Writing Improvement

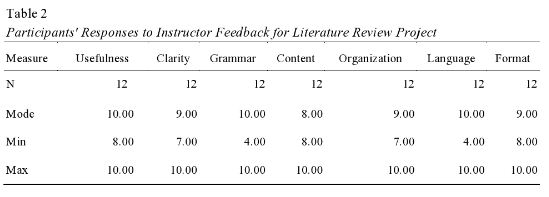

To foster a better understanding of how COM impacts students’

writing development, I adopted and modified Faigley and Witte’s taxonomy

of revision changes (see Table 2) to analyze whether text revision,

promoted in the COM-based classroom, would bring about writing

improvement.

Eight selected students made 60.9 percent of text-based changes

(i.e., a revision type that alters the meaning of a text) in their

revised drafts, which implies that they attempted to modify the content

of their work and make it more comprehensible to readers, whereas 39.1

percent of the students made the surface changes, which refer to

overhaul of the writing mechanics such as misspelling and inappropriate

use of punctuations. Regarding the size and function of revision, the

students mostly changed their drafts at the sentence level (37.5%)

(e.g., “sometimes, we are very annoyed, as there are too

many ^ is so much homework to do”) with cosmeticfunction

(38.3%) (e.g., “When choosing a career, we should make ^ strike a balance between the above three

aspects – interest, money ^ salary, and prospect”)

(see Table 3). Although the sentence-level (size of revision) and

cosmetic-oriented changes (function of revision) might not have

necessarily resulted in a major revision of the text, they were likely

to raise students’ awareness of the syntax and lexical elements of their

writing (comments from the other portfolio reader); also, despite

improvement in most of the revised drafts, students should perform

revision changes beyond the sentence and cosmetic level in order to give

a new look to a text in terms of its rhetorical structure and register

features.

DISCUSSION

COM as Good Feedback Practice

Although some students felt snowed under with written

commentary, COM was viewed as a good feedback practice that diagnosed

students’ strengths and weaknesses in writing and suggested to them how

to close the gap between desired and existing writing levels (Nicol

& Macfarlane-Dick, 2006). Not only did COM motivate students in

this study to improve their interim drafts, but it also made them well

aware of the benefits of formative feedback and how it productively

impacted the learning of writing. COM also maximized the instructional

power of assessment by drawing students’ and teachers’ attention to

learning of writing rather than assessment of writing.

COM as an Effective Learning Tool

Unlike other means of giving feedback, COM seems to serve as an

effective learning tool that facilitates students’ writing development

in a supportive environment over time. As opposed to the comparison of

student ability through grades and marks, COM aims to emphasize learning instead of performance (e.g., to improve

discourse-related aspects of writing), develop learner independence in

writing, and promote self-reflective capacity in the learning process

(i.e., learning how to learn). Because of its process-oriented nature,

COM can be valuable in nurturing students’ revising skills (redrafting)

and meta-cognitive strategies (self-assessment) to improve writing

standards.

COM and Instruction in Revision

Though COM seems to enhance the overall quality of students’

writing, the text revision data indicated that their revision behaviors

still have room for improvement. Revision operations at the paragraph or

macro-structure level (e.g., major revision that alters the meaning of a

text) remain limited in the revised drafts. To ensure that COM can

benefit students’ writing development, provision of explicit instruction

in revision strategies before piloting COM is indispensable. Intensive

training on how to perform a major revision at the discourse-related

level is likely to warrant writing improvement.

CONCLUSION

In this study, although the students’ reactions to COM were

varied, the use of COM as a pedagogical and assessment tool has a role

to play in enhancing their capacity of self-regulated learning. Trying

out COM in EFL contexts seems worthwhile, as its instructional power can

harness learners’ potential in improving the quality of writing and

develop a new identity as self-reflective writers during the composing

process.

REFERENCES

Assessment Reform Group. (2002). Assessment for

learning: Beyond the black box. Retrieved from http://arrts.gtcni.org.uk/gtcni/handle/2428/4621

Belanoff, P. (1991). The myths of assessment. Journal

of Basic Writing, 10, 54–66.

Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., &

Wiliam, D. (2003). Assessment for learning: Putting it into

practice. New York, NY: McGraw Hill / Open University Press.

Faigley, L. & Witte, S. (1981). Analyzing revision. College Composition and Communication, 32,

400–414.

Hairston, M. (1986). On not being a composition slave. In C.W.

Bridges (Ed.), Training the new teacher of college

composition (pp. 117–124). Urbana, IL: National Council of

Teachers of English.

Huot, B. (2002). (Re)-Articulating writing assessment

for teaching and learning. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Lee, I. (2007). Assessment for learning: Integrating

assessment, teaching, and learning in the ESL/EFL writing

classroom. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 64(1), 199–214.

Nicol, D. J. & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative

assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of

good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199–218.

Ricky Lam is a teacher trainer working at the Hong

Kong Institute of Education. His research interests are peer review,

assessment for learning, and portfolio assessment. |