|

ESL writing teachers working in academic settings (e.g.,

high schools, community colleges, universities) seem to voice similar,

recurring concerns: How do I help students reach beyond the basics of

the five-paragraph essay? How can I motivate students to produce enough

work of increasingly higher quality? This article draws on writing

pedagogy to offer a set of teaching strategies and techniques for ESL

academic writing.

Four key concepts serve as a foundation: creativity,

systematicity, operationalization, and validation. First, creativity is

inherent in all humans, and writing teachers can cultivate originality

and artistry in students. Recognizing and stimulating a student’s

artistic side is imperative because it creates pleasure as well as

develops the writer’s voice. In my classroom, I emphasize that to write

well is an art as well as a skill. This emphasis implies that I am

teaching academic ESL writing from the perspective of traditional

academic skills, and also from the perspective of teaching writing as a

creative endeavor. Second, systematicity also promotes good writing. In

teacher development programs, teaching routines are encouraged because

they create security, support development, and potentially encourage

appropriate risk-taking in students. Also, famous authors tend to write

at certain times of the day in certain spaces (George, 2005), so

emerging writers should be encouraged to develop their own routines for

writing. Third, operationalizing the essay or research paper into

specific writing processes makes the work doable. The Chinese have a

saying that “To get through the hardest journey, we need take only one

step at a time, but we must keep on stepping.” Finally, validating an

ESL writer’s work remains crucial to supporting the emotional as well as

academic needs of second-language learners. I have found that emotional

validation parallels supporting the creative nature of my writers. In

this article, I apply these four concepts to ESL academic writing

instruction by means of these six teaching techniques: cultivating

fluency in writing via creativity, teacher modeling of writing

processes, reducing anxiety by breaking down the writing process into

smaller tasks, increasing the accessibility of writing processes via

collaboration, guiding revision, and achieving validity in assessment

through writing portfolios.

CULTIVATING FLUENCY IN WRITING VIA CREATIVITY

Many students, not just ESL writers, are afraid of the writing

process. Consequently, writing teachers and coaches may employ various

types of short, simple writing tasks (e.g., free-writing, in which

students write down whatever comes to mind; brainstorming, in which

students list ideas or details tied to their topic; and drafting, in

which students organize main ideas and supporting details tied to their

purpose or main argument―all of which may be observed but not be graded

by the teacher) that may help students relax and prepare for longer or

more complex writing tasks (which may ask the students to use specific

grammatical, semantic, or stylistic forms previously presented by the

teacher). Also, such exercises may help nervous writers draw on their

creativity, which is associated with left-brain functions (George,

2005). To specifically cultivate creativity, instructors may employ 3-

to 5-minute free-writes that use postcards, images of animals or

scenery, blank cartoons, or other kinds of unusual graphics as visual

writing prompts for warm-up writing tasks. Asking students to write in

response to these images may activate creativity, generate enthusiasm,

and cultivate enjoyment at the beginning of an ESL writing class.

However, to encourage self-awareness and student responsibility in

writing processes, I suggest varying the opening warm-ups between these

creative visual exercises and short quizzes. In my classes, the format

of these quizzes takes the form of timed free-writes, and the content

for the quizzes is self-reflection on writing processes. Examples of

prompts for the quizzes are: What did we talk about yesterday to improve

our writing? What have you learned about your strengths and weaknesses

so far?

TEACHER MODELING OF WRITING PROCESSES

Even at the elementary level, scholars assert that ESL writers

want to observe and experience authentic writing processes (Graves,

1994). Students perceive and personalize authenticity when teachers

model their own writing process. This shows ESL students that all

writers, even native speakers writing in their own language, must revise

their texts. In this way, modeling authenticates the writing process;

using texts generated by the student also serves to help students

witness their own process. However, using student writing as models can

be tricky; the teacher must walk a fine line between the need for

validation and revision. I overcome reluctance about the revision

process by modeling the process, using short excerpts of my own work in

progress. Next, I ask students to attempt their own revisions at

scheduled times during the semester. Finally, I note that participation

in personal and peer revisions also counts as assessment points toward

final grades.

REDUCING ANXIETY BY BREAKING DOWN THE WRITING PROCESS INTO SMALLER TASKS

Anxiety can overtake all kinds of writers, not just ESL

writers. Famous fiction writers have recounted that they build their

stories by writing small sections of the work, sometimes in random

order; this type of nonlinear thinking is well known to creativity

experts (Csikszentmihalyi, 1997). Second-language psychology recommends

breaking down the writing process into smaller tasks that sequentially

represent the writing process and “conscious movement towards goals”

(Oxford, 2001, p. 362; Bialystok, 1990). Because academic writing is a

formidable task, students can benefit by breaking it down into smaller

portions. For example, for a research paper, these portions can be used:

collection of evidence (i.e., research); topic selection and thesis;

outline of main ideas and supporting details; reference page; adding

references in the text (i.e., indirect and direct citations);

introduction; conclusion (i.e., summary plus meta-commentary);

transitions; title page; and formatting guidelines. Each of these

sections can be adjusted to the students’ proficiency. To cultivate

independence in the writing process, I have students submit their papers

with a checklist that is designed to acknowledge that they have

completed all the requirements for each section (see appendix). This coversheet is thoroughly

reviewed during the first week of class and reviewed throughout the

term.

INCREASING THE ACCESSIBILITY OF WRITING PROCESSES VIA COLLABORATION

One way to counteract any negative feelings about revisions is

to ask students to work collaboratively. When two ESL students or a

small group generate or revise texts together, the process becomes

dynamic and collaborative. ESL students may scaffold onto each other’s

writing processes, accept peer revisions, and create texts reflecting a

higher level of academic register (in terms of vocabulary, organization,

correct grammar, and stylistic nuance) together better than they could

alone. In the classroom, setup can be varied to encourage

collaboration. Activities can also be varied from solitary writing

exercises to pair or group activities, with both types of activities

either timed and untimed. In addition, sometimes I create a

scrambled-sentences activity from a text written by a collaborative

pair. First, the class re-sequences the sentences. Then, I divide the

class into small groups, with the collaborating pair of writers

functioning as class consultants for the activity. The class works in small groups to revise and expand upon the text, thereby creating a

new, longer version of the original draft. The consultants circulate

and offer advice, comments, and support to their peers.

GUIDING REVISION

ESL students can help each other with the writing process

during a guided revision activity. A clear set of peer review guidelines

is needed when requesting students to participate in peer-review

activities. Many ESL writing textbooks, such as Oshima and Hogue (2006),

have peer review guidelines in their appendices; the Internet also has a

wide selection as well. As a teacher, I regularly hold mini-conferences

with student writers throughout the semester. Usually, I hold a

conference with a student for 10 to 15 minutes, or I meet with a group

of students who share a similar issue. For example, if a student needs

help paraphrasing or citing references, I will sit with her and listen

carefully as she tells me about a section of her work. Then, we will

look at this section, and I will ask her to point out problem areas.

Sometimes, I will point them out and ask her to revise them with me. My

writer’s conferences are all individualized instruction, yet they are

based on allowing the writer to speak about areas that both the writer

and the teacher feel need revision.

ACHIEVING VALIDITY IN ASSESSMENT THROUGH WRITING PORTFOLIOS

It makes practical sense that writers be assessed by what they

produce. Many creative and rhetorical writing programs in the United

States use portfolio-based assessment for writing courses; research

shows that portfolio assessment can accurately index proficiency and

skill (Huot & O’Neill, 2008). For ESL writers, this alternative

assessment can help relieve stress and anxiety related to exams and

testing. Assessment also directly validates the writer: This is your

work; this is what you have created over time in my class. For example, I

assess my ESL writers not only by how well they write in terms of

content, correct grammar, punctuation, and formatting, but also in terms

of how many times they revise, how many times they meet with a peer

editor, and how many times they meet with me for writer’s conferences.

(For advanced students who need fewer revisions, I ask them to serve as

writing consultants.) In addition, I ask each writer to keep a dialogue

journal, which I assess by weekly word counts. Finally, I assess the

students by the number of essays they bring to completion, which

includes having submitted two drafts.

CONNECTING THE CONCEPTS

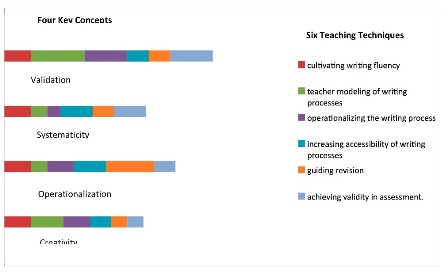

Figure 1 illustrates how these concepts and elements are closely related.

Figure 1 visually represents the connections between

validation, systematicity, operationalization, and creativity. Because

these terms are abstract and because the composition of each classroom

is unique in terms of learner identity as well as linguistic fluency,

this figure is an approximation. But as the graph portrays, generally

speaking, validation is most deeply influenced by teacher modeling of

writing processes. Systematicity appears to be most influenced by a

combination of increasing accessibility in the writing process and

through validity in assessment. For operationalization, revision is key.

Finally, creativity is well balanced throughout the six teaching

techniques; I have found that appealing to real-life (culturally

sensitive and culturally known topics and subjects) stimulates the

highest levels of enthusiasm and achievement.

CONCLUSION

I feel that teaching academic writing is an exciting ESL field.

Increasing the accessibility and effectiveness of writing instruction

remains a daunting challenge. This challenge can be overcome if we

consider writing as both a creative process and an academic product. By

incorporating creativity, systematicity, operationalization, and

validation in the ESL classroom and by dividing the academic writing

task into six basic elements, both teachers and students will enjoy the

journey. My writing mentor said to me many times: “Writing is thinking

on paper. You can’t learn rocket science in one day, but you can

eventually master the scientific components if you deconstruct the

process. Take it nice and easy.” Cultivating fluency, segmenting the

writing process into portions, writing together with your students,

alternating production styles, tapping into peer scaffolding as well as

personalized mini-conferences, and finally, choosing portfolio

assessment―all these things may encourage your ESL writers to create

more and better work.

REFERENCES

Bialystok, E. (1990). Communication strategies: A

psychological analysis of second-language use. Oxford, UK:

Blackwell.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Creativity: Flow and psychology and the discovery of

invention. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

George, E. S. (2005). Write away: One novelist’s

approach to fiction. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Graves, D. (1994). A fresh look at writing. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Huot, B., & O’Neill, P. (2008). Assessing

writing: A critical sourcebook. New York, NY: Bedford/St

Martin’s.

Oshima, A., & Hogue, A. (2006). Writing

academic English, level four (4th ed.). White Plains, NY:

Pearson Longman.

Oxford, R. L. (2001). Learning styles and strategies. In M.

Celce-Murcia (Ed.)., Teaching English as a Second or Foreign

Language (3rd ed., pp. 359-366).

Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle.

Valerie Sartor is an ABD student at the University of

New Mexico. She is interested in bilingual education for minorities and

teaching academic writing to ESL and ELL students. Her dissertation

focuses on Mongolian minority bilinguals in North

China.

APPENDIX

WRITING ASSIGNMENT CHECKLIST FOR ADVANCED WRITING

[Note to reader: I copy this cover sheet for every

typed assignment and staple it to my assignment.]

- I checked my assignment to make sure I used

- complete sentences

- correct spelling

- correct punctuation

- I typed this in Times New Roman 12 point font, double spaced.

- The assignment is on plain white paper printed on one side.

- I used the spell check function to check my spelling.

- The margins are one inch: top, bottom, right, left.

- I wrote this work myself; I did not cut and paste other people’s work.

- The register is academic; I have chosen my words and style carefully.

- My word choice is not casual; the register is academic.

- I do not have in my paper the following: really, very, great, cool, super.

- I varied my sentence length. Short sentences have more power.

- The topic is carefully thought out.

- The introduction has a compelling opener.

- The topic sentence of each paragraph is a clear assertion that serves the thesis.

- The other sentences in the paragraph support the assertion.

- My conclusion does not simply repeat the main argument;

rather, it also summarizes discoveries and explains potential

implications, generalizations, or applications.

- This assignment has the 1,000-word minimum.

- A UNM style cover sheet is attached.

- My paper has a header with my assignment (Draft 1 Argument - Sartor) and page number.

- The title of my paper is creative and informative.

- If applicable: This assignment has quotes and references, specified by the teacher.

SIGNATURE__________________________________

DATE _______________________ |