|

The Academic Literacies Symposium was held at the Indiana

University of Pennsylvania in February 2010. It provided an opportunity

for both graduate students and faculty to share research and engage in

conversations on interdisciplinary academic literacy pedagogies. This

symposium hosted two distinguished scholars: Dr. Alan Hirvela from The

Ohio State University and Dr. Suresh Canagarajah from Pennsylvania State

University. It involved dissertation roundtables and concurrent

presentation sessions, as well as poster presentations. At this event, I

had the opportunity to present a study entitled “Going Beyond

Grammar-Based Feedback in Writing Classrooms: A Small-Scale Study of

Three EFL Teachers.”

The issue of grammar in teaching writing and in giving feedback

to writing assignments has been disputed for the past few decades.

According to Reid (2001), responding to students’ writing has become an

essential and central part of teaching writing and has shifted from

evaluating the finished product to evaluating different stages of the

writing process, from product-based responses to progress-based

intervention. This presentation focused on my exploration of EFL writing

teachers’ feedback and responding-to-writing practices and

philosophies, provided insights into how feedback is given differently

by different teachers, and empirically investigated the role of

grammar-based feedback in EFL writing teachers’ philosophies and

practices.

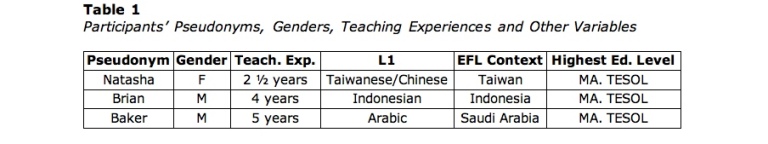

Three EFL teachers, Brian, Natasha, and Baker (pseudonyms),

were asked to provide one-page feedback philosophies. Table 1 gives a

detailed description of the participants:

A week later, the participants were individually contacted to

respond to five open-ended questions dealing with their philosophies.

These questions were (1) What does feedback (effective and ineffective)

mean to you in writing classes? (2) What issues in the writing

assignment do you usually stress? (3) What is the role of grammar in

responding to students’ writing? (4) What is the relationship between

good writing and good grammar? (5) How would you grade a paper that is

full of grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors? Ten days later, they

were given a short writing assignment by an ESL student, and they were

asked to respond to it and provide one paragraph of written

feedback.

This limited-scale, qualitative study revealed the following

six important issues pertaining to EFL teachers’ feedback theories and

practices. The first five issues synthesize participants’ perspectives.

The last one includes my own evaluation of participants’ responses and

feedback practices. Please be advised that all of the feedback

attributes used (e.g., descriptive, improvement-friendly, relieving,

vague, prescriptive, and so on) are my own and are based on the

participants’ written as well as oral responses.

First, the three participants believe that giving feedback is

important and indispensable in developing students’ writing skills. The

end (better writing skills) seems to be the same though the means is

different (grammar for Brian, content for Natasha, and both content and

form for Baker).

Second, there is an explicit as well as implicit reference to

audience and its significance in feedback-giving practices. As the

participants directly or indirectly say, this audience-awareness “stuff”

is a reaction against their own EFL context norms and against the way

they were taught and required to teach.

Third, there is consciousness on the part of the three

participants of new trends (process writing, social process,

collaborative learning approach, peer response, situated learning, and

the like). Undoubtedly, this could be ascribed to the education they had

(master’s in TESOL) and the graduate degrees they are currently

pursuing (PhD in composition and TESOL).

Fourth, in their responses, the three participants point out

that good writing leads to good grammar, but good grammar does not lead

to good writing. It seems to me the idea that we become better writers

by actually writing is Natasha’s main feedback focus but not Baker’s or

Brian’s. There is this consensus among the participants’ responses that

grammatical difficulty leads to reading difficulty. In other words, the

three participants asserted that a paper full of grammar and formalist

problems (mechanics) makes the process of responding “harder” and “more

annoying,” as they put it.

Fifth, according to the three participants’ responses, it seems

that the more feedback items there are on a student’s piece of writing,

the less engaging and the less relieving feedback becomes from a

student’s perspective. All the participants state clearly that choosing

to mark every single error or writing problem creates stress for the

students. This in turn makes feedback futile and unfulfilling as far as

students and the writing process are concerned.

Sixth, participants provided varying and diverse feedback characteristics:

- Too much judgment and prescriptiveness. Participants give

feedback in a judgmental and prescriptive manner: for example, revise, delete, right, not a good idea,

wrong.

- Too much vagueness. Participants give vague feedback: for

example, revise, something is missing, this needs a linking

word, take this out)

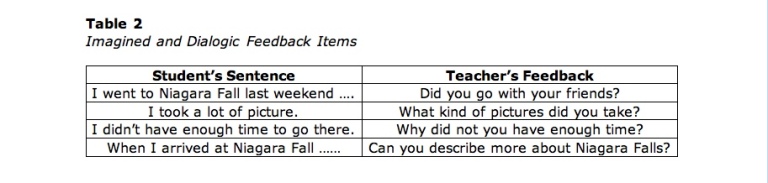

- Few instances of descriptiveness and improvement stimulation:

Participants give descriptive feedback, such as “Can you describe more

about Niagara Falls? Like the surrounding, the environment, tourists.”

Please see Table 2 below in relation to what I call imagined and

dialogic feedback items.

- Too many grammar-based and formalist feedback items: definite

and indefinite articles, comma, tense, passive voice, word choice,

plural formation, subject-verb agreement.

In short, the results of this small-scale research study

indicated that the EFL teachers had varying theories and practices for

responding to writing, though the feedback priorities overlapped at

times.

REFERENCE

Reid, J. (2001). Responding to ESL students’ texts: The myths

of appropriation. In P.K.Matsuda & T. Silva (Eds.), Landmark Essays on ESL Writing. 209-224. Mahwah, NJ:

Hermagoras Press.

Ibrahim Ashour holds a PhD in composition and TESOL

and is currently an ESL and developmental writing instructor at the

Harrisburg Area Community College. He administered the Arabic program

and taught Arabic at Penn State Altoona and the Indiana University of

Pennsylvania. He has extensive ESL, EFL, Arabic, writing center, and

composition teaching experience. His primary research interests include

teacher supervision, technology and literacy, bilingualism, and

composition theories and models. |