|

A substantial number of ESL students are present in U.S.

universities and colleges (Matsuda, 2006). In many cases, these students

are required to enroll in a freshman composition course in their first

year. At a university where I work as an instructor, two types of

freshman composition courses are available to entering students. One is a

regular composition course in which domestic students are the

predominant population. The other is a composition course specifically

designed for ESL students. The latter course is offered exclusively to

nonnative-English-speaking (NNES) students who require additional

language support. This article is a report of the action research study

conducted in a section of the aforementioned ESL composition course of

which I was an instructor.

Statement of the Problem

The underlying motivation of this study stemmed from my strong

desire to be reflective in my practice as an ESL composition instructor.

In today’s composition classroom, teaching through the process approach

is a commonplace practice. Therefore, instructional feedback in both

oral and written forms holds significant relevance to the effectiveness

of second language (L2) writing instruction. However, it is often

difficult for instructors to evaluate their performance during the

course of a semester for various reasons—one major constraint is perhaps

time. Although universities typically conduct summative evaluations at

the end of every semester, these have little value when it comes to

being reflective in the ongoing process of classroom teaching. Hence, I

felt the need to evaluate the effectiveness of my instructional feedback

as an integrative part of teaching.

Proposed Solutions

To mediate the limitations of the summative evaluation, I

devised a quick 5-minute survey (Appendix) to elicit evaluative

information from students pertaining to written feedback that I had

provided about their writing hoping to improve my teaching before the course was over rather than after. In this undertaking, I followed the basic

principles of participatory action research, which focuses on an

emergent process of identifying issues and responding to the issues as

an active participant (Greenwood, Whyte, & Harkavy,

1993).

There were two overarching purposes in conducting this action research:

- to examine whether students found my overall written feedback useful to improving their writing

- to understand the relationship between different areas of

feedback and its usefulness as perceived by students to improving their

writing

Instructional Approach to the Course: Sequenced Writing

This ESL composition course takes a particular approach to

teaching writing, sequenced writing (Leki, 1992),

which is the conglomeration of two core teaching approaches: genre based

(Byram, 2004) and process (White, & Arndt, 1991).

The course requires students to produce written work in four

genres: personal narrative, literature review, interview report, and

argumentative essay. Each project takes approximately 3–4 weeks to

complete. At the time of this research, students had already completed

the first two projects: personal narrative and literature review. Hence,

the study investigated students’ perceptions about the feedback they

had received on these two projects.

Method

Participants

Data were collected from students during a class period. I

explained the purpose of the survey and asked them to respond

anonymously. Eleven Chinese students and 1 Indian student out of a total

of 15 students in my class responded to the 5-minute survey (3 students

were absent).

Instrument

For the two projects, my feedback was targeted at five core

areas of students’ written products: content, grammar, language,

organization, and format. The following provides a brief description of

my feedback practice in these five areas.

Content. I evaluate content according to the

genre of writing task at hand and its requirements. For example, for

the literature review project, students were required to produce a

summary of several academic sources on a topic of their choosing. Use of

nonacademic sources such as blogs violates this premise and hence my

feedback on content would prompt students to address

the issue.

Grammar. Grammar refers to grammatical

errors that hinder the effective communication of the message that

students attempt to convey. My feedback is typically targeted at

grammatical errors that are likely to prevent potential readers from

understanding or interpreting the meaning of a given sentence. Also, I

correct recurrent grammatical errors in students’ papers.

Language. I provide feedback on problematic

lexical use when students’ lexical choice violates collocations,

semantic rules, or pragmatic rules, which is likely to lead to

communication problems.

Organization. Organization means the overall

structure of a paper. My feedback aims at helping students order their

ideas in a coherent manner to achieve a better presentation. This

includes suggestions for combining, deleting, moving existing

paragraphs, or adding a new paragraph(s).

Format. Format refers to the use of the

specific format required for this course. Because APA style is a default

format that every student is required to use, my feedback on format

aims to guide students to set up their papers in APA. Format feedback

also extends to the use of punctuation and other mechanical aspects of

writing.

Based on my feedback practice, I created a survey that contains

two sets of 7 questions for a total of 14 items (see Appendix). The

items were designed to identify whether students perceived that they

received enough feedback on the five areas outlined above. Also, in order

to evaluate my feedback in terms of its clarity and usefulness, a few

additional items were included. Participants were requested to indicate

the level of their agreement to each of the items on a 10-point Likert

scale, 10 indicating strongly agree and 1 indicating strongly disagree.

Analysis

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed via frequency analysis and Spearman rank

correlation. For this purpose, participants’ responses were converted

into two sets of seven ordinal variables based on the corresponding

items on the survey: usefulness, clarity, grammar, content,

organization, language, and format. The following is a brief explanation

of what these variables indicate.

Usefulness. This variable indicates

participants’ perceived level of usefulness about instructor’s feedback

to improve their writing skills.

Clarity. This variable indicates

participants’ perceived level of clarity about instructor’s overall

feedback.

Grammar/Content/Organization/Language/Format. This variables indicate participants’ perceived level of

satisfaction on the amount of feedback they received on the five

areas.

Using these variables, I conducted a frequency analysis to

understand the distribution of participants’ responses. Then I ran a

Spearman rank correlation analysis to examine the relationship between

usefulness/clarity and the five remaining variables: grammar, content,

organization, language, and format. Because participants evaluated my

feedback for two different projects, the same procedure was repeated for

another set of the seven variables.

Analysis of Results

Students’ Evaluations of my Feedback

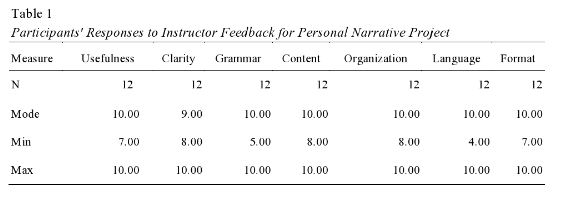

Tables 1 and 2 present a summary of participants’ responses to

the feedback they received on their papers for the two projects. The

results indicate there is a similar pattern between their responses to

my feedback for the personal narrative and literature review

projects—mode is a general indicator of overall pattern of participants’

responses, and it indicates participants perceived my feedback quite

positively as it falls between 8 and 10 for all categories for both

projects.

For personal narrative, the minimum values of grammar and language are much

smaller than those of the other categories. A separate analysis revealed

one participant marked 5 for grammar and 4 for language. With the exception of this one participant,

the overall responses of participants to those two categories were also

positive.

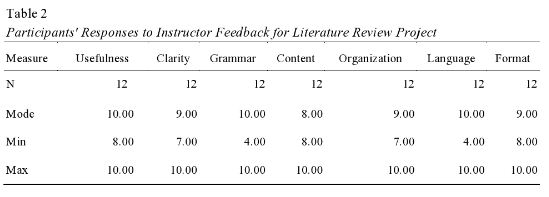

For literature review, the level of satisfaction is again

somewhat less with respect to grammar and language, as indicated by mode and minimum values.

This is perhaps due to the fact that I do not correct every single

grammatical error or language problem on students’ writing, which could

have been what they expected me to do. It is not uncommon for students

to expect instructors to correct every mistake because this is pervasive

in EFL countries where grammatical accuracy is strongly emphasized

(Ferris, 2003), and all participants of this study were former EFL

students.

Relationship Between Student Satisfaction and Areas of Feedback

In order to examine the relationship between the five areas of

feedback and participants’ perceived usefulness of my overall

feedback/perceived clarity of feedback, I ran a Spearman correlation

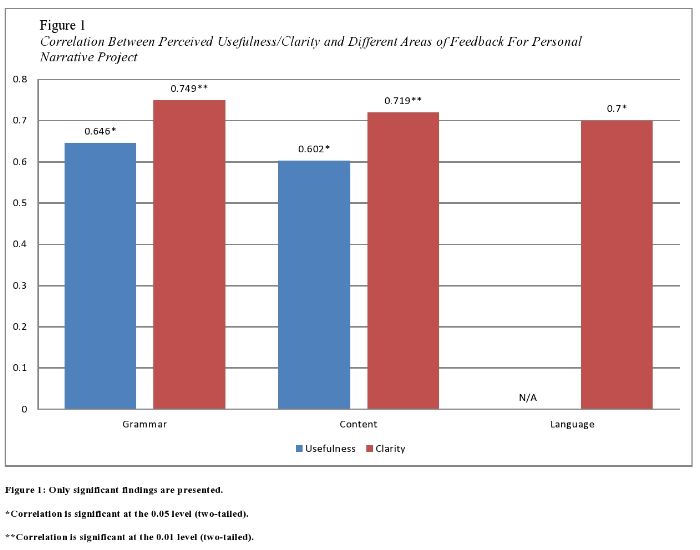

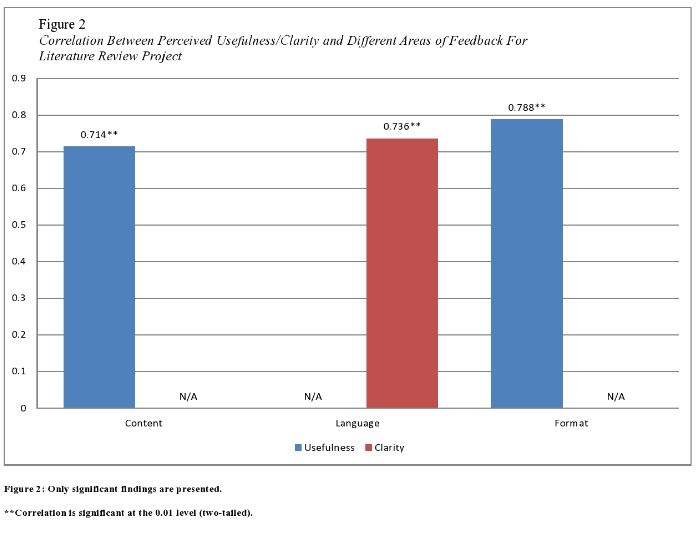

analysis. Figures 1 and 2 show the results of this analysis.

For the personal narrative project, usefulness and clarity are highly correlated with grammar and content: usefulness and grammar (rs = 0.646), usefulness and content (rs = 0.602), clarity and grammar (rs = 0.749), and clarity and content

(rs = 0.719). These results

suggest my feedback on grammar and content were perceived to be clear and

useful by students. In addition, clarity is highly

correlated with my feedback on language, which

indicates that students perceived my feedback on language to be clear.

As for the literature review assignment, the picture is

somewhat different. Usefulness is highly correlated

with content and format, whereas clarity is correlated with language. These results indicate that feedback on

content and format were considered useful by students in improving their

writing. Also, they perceived my feedback on language to be clear and

positively related to their level of satisfaction on language.

From the results of the analyses, a few inferences can be drawn

with regard to the relationship between the areas of feedback and

students’ perceptions regarding their writing skill

improvement:

1. Some areas of feedback may contribute more to

students’ writing skill improvement due to the nature of the writing

task.

As the results indicate, for personal narrative the students

perceived my feedback on grammar as useful to improving their writing.

However, for literature review, my feedback on format was perceived as

useful by students but not my feedback on grammar. This was to me the

most interesting finding, and it makes sense if we assume writing in

different genres calls for different writing skills. In this case,

literature review was not a genre that students were familiar with.

Also, this is the genre in which the use of APA is heavily emphasized.

As such, I can understand why students positively valued my feedback on

format.

2. Feedback on content may be useful for students to

improve their writing across different genres.

My feedback on content was perceived useful by students for

both projects. This is perhaps because my feedback on content aims to

curve out what characterizes a particular genre of writing—that is, to

help them understand what elements define personal narrative or

literature review as an independent genre of writing. Hence, defining

the elements specific to the genre in question and providing clear

explanations of how to incorporate the identified elements into

students’ writing may be important for effective feedback practices in

the genre-based L2 writing classroom.

3. A clear understanding of instructor feedback may be

important for students to improve their writing.

This is probably a commonsense understanding that many writing

instructors may very well share. As shown in the results of correlation

analyses for personal narrative, usefulness and clarity are positively

correlated with the same areas of feedback. But this is not the case for

literature review, in which clarity is correlated with only language.

At this point, I cannot offer a clear explanation of why clarity is not

correlated with the same areas of feedback as usefulness. All I can say

is that different writing tasks change the dynamics of how clarity and

usefulness contribute to students’ perceived level of satisfaction about

instructor feedback. This again points to a possibility that each

writing task has its own dynamic relationship with areas of feedback.

Hence, some areas of feedback may be more effective for one project but

not for the other.

Final Reflections

As with any research study, the present study is not free from

limitations. One limitation is the generalizability of findings due to

the small sample size. I did not intend to generalize my findings in the

first place because I conducted this action research essentially to

evaluate my own practice as an L2 writing instructor. Therefore,

findings that I present here need to be carefully interpreted and

considered tentative.

Another limitation of the study is the use of a Likert scale

alone to evaluate my feedback practice. The choice of the research

design was largely due to my concern for time and also an essential

issue with participatory action research—potential conflict of interest;

my presence may have affected their responses. To minimize the effect

of this potential issue, I decided to use a Likert scale, which is

time-efficient and also a more impersonal means to elicit students’

opinions compared, for example, to interviews. For future research,

however, if the time allows, I would include some open-ended questions

in the survey so that students can express their feelings and opinions

less restrictively. It would most certainly provide me with more

detailed accounts of their perceptions about my feedback practice and

possibly more concrete directions that I might take to improve my

teaching.

One notable realization that impacted my teaching is that,

depending on the nature of writing assignments, adjustment in

instructional focus on areas of feedback may be required for more

effective instructional feedback practice. Giving feedback according to

the same principle regardless of writing tasks may be comparable to a

doctor prescribing aspirin for all your medical problems, which is

certainly not an effective practice. I learned that it is important to

sensitize myself with the changing dynamics of writing in different

genres and flexibly adjust my feedback practice to the specific nature

of writing task.

The notion of reflective teaching is highly valued in our line

of business, and yet it is a difficult to task to evaluate our own

instructional practices in the ongoing process of teaching. My

undertaking in this action research was a challenge to this

preconception that evaluating our teaching practice is time-consuming

and difficult to conduct. In the end, this small research proved to me

that it is possible to integrate evaluation into daily practice without

spending much time. This extra effort for better accountability of my

own teaching practice helped me understand more about students and how

they perceived my instructional feedback.

Overall, this entire experience led me to further reflect on my

teaching practice and to realize how important and useful it is to

build evaluation of my own teaching practice into the ongoing process of

teaching. For better learning, students need to receive feedback from

us, and for better teaching, we also need feedback from them because

teaching and learning are essentially inseparable just like fish and

water.

References

Byram, M. (2004). Genre and genre-based teaching. In The Routledge Encyclopedia of Language Teaching and Learning (pp. 234-237). London,

England: Routledge.

Ferris, D. R. (2003). Response to student writing:

Implications for second language students. Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum.

Greenwood, D. J., Whyte, W. F., & Harkavy, I. (1993).

Participatory action research as a process and as a goal. Human

Relations, 46(2), 175–191.

Leki, I. (1992). Building expertise through sequenced writing

assignments. TESOL Journal, 1(2),

19–23.

Matsuda, P. K. (2006). The myth of linguistic homogeneity in

U.S. college composition. College English 68,

637–651.

White, R., & Arndt, V. (1991). Process writing. London, England: Longman.

Appendix: Instructor Feedback Student Satisfaction Survey

This survey is designed to evaluate the level of your

satisfaction regarding the feedback you received from the instructor on

your writing assignments: Personal Narrative and Literature Review.

Please read each statement carefully and circle the numerical value

which best represents your level of agreement with each statement.

Section 1: Personal Narrative

1. I think the instructor’s feedback was clear to me.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree

2. I think the instructor’s feedback was useful for me to improve my writing.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree

3. I received enough feedback on grammatical errors.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree

4. I received enough feedback on content.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree

5. I received enough feedback on organization.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree

6. I received enough feedback on language (vocabularies, idioms, and phrases).

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree

7. I received enough feedback on format.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree

Section 2: Literature Review

1. I think the instructor’s feedback was clear to me.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree

2. I think the instructor’s feedback was useful for me to improve my writing.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree

3. I received enough feedback on grammatical errors.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree

4. I received enough feedback on content.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree

5. I received enough feedback on organization.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree

6. I received enough feedback on language (vocabularies, idioms, and phrases)

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree

7. I received enough feedback on format.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree |