|

Introduction

The proliferation of American universities abroad in recent

years has also prompted the growth and development of writing centers in

international contexts (Bazerman et al., 2012; Eleftheriou, 2011;

McHarg, 2011; Thaiss, Brauer, Carlino, Ganobcsik-Williams, &

Sinha, 2012). This expansion has transformed the way writing centers are

established and shaped, as many of the clients are multilingual

learners. While it is not unusual for writing centers worldwide to

devote a considerable amount of time to international and ESL students,

it is a relatively new phenomenon to have multilingual learners

supporting their multilingual peers (Eleftheriou, 2011; Ronesi, 2009,

2011). This demographic shift has transformed the nature of peer tutor

training, and this project sought to contribute to the development of

this shift. In this article, I describe one training activity I

developed and implemented at Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar’s

Writing Center.

The impetus for this project was Lynne Ronesi’s publication,

“Theory In/To Practice: Multilingual Tutors Supporting Multilingual

Peers: A Peer-Tutor Training Course in the Arabian Gulf” (2009). Ronesi

showcased the course syllabus she developed to appropriately build upon

the strengths of multilingual peer tutors who could then support their

peers. She built on existing scholarship by emphasizing the role and

value of peer tutors who share similar and recent experiences in their

own educational experiences. However, Ronesi went further by challenging

the U.S.-centric scholarship and looking for ways to expand upon it in

the Middle Eastern context. She articulated her approach to discussing

“notions like additive and subtractive bilingualism and code switching

as well as prestige, status, and identity with regard to first and

second language use” (p. 80); Ronesi noted that most of these language

issues were already employed, unconsciously, by the peer tutors in their

everyday lives. Ronesi’s work built upon established scholarship

related to ESL, cultural studies, and writing centers, and her work has

offered a solid foundation for peer tutor training programs in the Gulf

region.

In addition to Ronesi’s article, I have been inspired by the

growth and development of peer tutoring initiatives around Doha. Through

my participation in Doha Writing Center Network meetings, I listened to

many writing center directors proclaim resounding success of peer

tutoring programs. Many directors expressed enthusiasm about the

increase in the number of students visiting the center, enthusiastic

faculty support, and more. They all professed to attracting and

recruiting high achievers—consequently, many writing center directors

looked to faculty for recommendations. I also discovered that, despite

being situated in the same context, Doha, the various training programs

were considerably different at each institution. Some institutions had

absolutely no training, assuming that selected tutors were sufficiently

competent, while others required new hires to go through 15 hours of

training prior to work. With these vast differences across the

institutions, I felt empowered with a certain kind of liberty in

developing my own peer tutor training program in accordance with my

expertise in TESOL, writing center pedagogy, and my professional

experiences over 7 years in Doha.

At my current institution, Virginia Commonwealth University in

Qatar (VCUQatar), which was established in 1998, there had never been an

attempt to develop a peer tutor program. Faculty and staff repeatedly

issued warnings that “The students’ English is not strong enough” and

“They are busy students and they don’t have time.” However, with the

future budget always an uncertainty, the talk of

success with peer tutoring at other institutions, and the increased

workload for our understaffed center, I decided it was worth an attempt.

I researched the programs that had been developed at neighboring

universities, consulted with experienced colleagues, consulted WCENTER

and other writing center resources, and formulated a plan.

VCUQatar launched its first semester of peer tutoring during

the spring 2012 semester. Recruitment and training (a series of

observations, readings, and workshops) ensued for a number of weeks.

Finally, a sash ceremony was held to mark training completion and the

tutors began holding their own tutorial sessions. I felt that my dreams

were at last realized, and the VCUQatar Writing Center was on the path

to developing a culture of collaboration, peer support, and

writing—everything the current writing center literature indicates

centers should strive to achieve.

A Reality Check

From my standpoint, the center was thriving. Although my office

is located down the hall from the central writing center, I frequently

pass through the main area. Any time I walked by and the peer tutors

were on duty, I sensed a site of vibrant activity. Students were

actively engaged in conversation with peer tutors, and there were many

faces I had not seen in the writing center previously.

Unfortunately, the old adage “don’t judge a book by its cover”

prevails, and I quickly discovered this when I began reading the

submitted tutorial reports. What I was seeing in the writing center was

not at all clearly articulated in the written summaries. First, a brief

word about our reporting system: Our online reporting database

(developed in-house by our database developer) was set up so that,

initially, only professional staff had access to the

system.1 Consequently, peer tutors were required

to write all reports, submit them to me, and then I would process them

through the database and send them to the faculty members on behalf of

the peer tutor. All tutorial sessions are reported to the faculty unless

the student requests it remain confidential.

In reviewing the written summaries, I could see that the peer

tutors were weak in their tutorial report writing skills. Although they

had been selected for the peer tutor positions because of their

relatively strong English abilities, report writing is a specialized

genre to which they had previously not been exposed sufficiently. We had

reviewed a few brief examples in the course of training, but clearly it

had not been enough. Most concerning to me, however, was that this was

what faculty would be seeing. As this was the first semester launch of

the peer tutor employment, I felt the pressure to establish a solid

program foundation.

Taking Action

I immediately recognized two issues: 1. I have struggled with

report writing myself, and 2. many of the reports written by tutors were

repetitive in that they covered the same topic.2

This became a ripe opportunity for our next training workshop, but I

struggled with how to approach the topic. I reverted back to standard

ESL classroom techniques and recognized the need for providing written

models. Furthermore, I felt that it was important to maintain the

integrity of writing center practice by fostering a sense of

collaboration and mutual production of texts, as opposed to directive

instruction.3

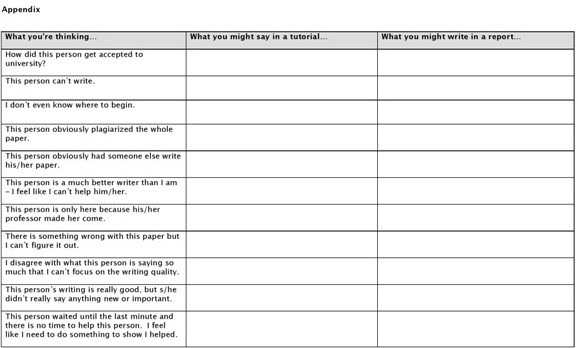

The result was my development of the template chart. This chart includes three columns: “What you’re thinking,”

“What you might say in a tutorial,” and “What you might write in a

report.” The scenarios in the left-hand column, “What you’re thinking…”

came directly from the tutors themselves; these comments had been

repeated to me many times verbally, so they were good launching points

for discussion (and much

laughter, as tutors could

easily identify with them and reflect on their tutoring experiences).

Working together, we drafted language in order to appropriately and

professionally respond to the potential client verbally, as well as in

writing to the instructor. While the peer tutors worked to complete the

chart together, I offered some suggestions, posed questions, and we

worked through revisions collaboratively and interactively. The final

production resulted in a reference chart with template language that can

be tailored for individual conferencing and reports.4

Reflections & Future Research

This activity served a wide variety of purposes. Specifically, it provided

- a low-stakes environment for learning and collaboration during training,

- solid language structures for sensitive conferences and report writing, and

- a developmental step for tutors to become professionals.

Tutors became more aware of the genre of report writing, with a

distinct attention to audience, purpose, and tone. We were also able to

discuss the value of writing templates and how they differ from

plagiarized work.5 Tutors are now able to

comfortably and confidently speak with peer clients as well as send

written reports to faculty. Finally, it simply became a time-saving

tool. Tutors are often under pressure to finish working with clients and

complete tutorial session reports before their shift ends. Having the

report template language can facilitate faster responses and a more

effective use of tutor time.

The verdict is still out in terms of the long-term outcome of

this activity. Have the tutors internalized the activity? Has it created

too much structure in report writing, or will they still be willing to

break out of the box? How will faculty respond if they begin to see

repeated, similar reports (and will they even notice or comment)? What

other unintended consequences will result?

We have just begun the start of a new semester at VCUQatar,

which means the start of a new cycle of recruiting, hiring, and training

peer tutors. It is hoped that this document, in its blank template

form, can be used as a training opportunity for newly hired peer tutors.

Furthermore, these completed documents can serve as an ongoing

professional development activity for continuing and new

tutors.

End Notes

1 Credit goes to Mirza Baig, without

whose constant support we would be technologically lost!

2 It would be valuable, in a future

study, to see how similar or different reports are in different

contexts—I would hazard a guess that they contain very similar language.

At present, however, there has been very little research related to

tutorial reports.

3 I acknowledge that directive versus

nondirective instruction is a very controversial topic in TESOL and

writing center pedagogy. However, for the purposes of this activity, I

believe a collaborative approach was most appropriate.

4 See Appendix.

5 For more on templates in academic

writing, “They Say/I Say” (Graff, Birkenstein, & Durst, 2012) is

an excellent source.

References

Bazerman, C., Dean, C., Early, J.,

Lunsford, K., Null, S., Rogers, P., & Stansell, A. (Eds.).

(2012). International advances in writing research: Cultures,

places, meaures. Fort Collins, CO: The WAC Clearinghouse and

Parlor Press.

Eleftheriou, M. (2011). An exploratory study of a

Middle Eastern writing center: The perceptions of tutors and

tutees. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of

Leicester, Leicester.

Graff, G., Birkenstein, C., & Durst, R. (2012). "They say/I say": The moves that matter in academic writing

with readings (2nd ed.). New York: W.W. Norton &

Company, Inc.

McHarg, M. (2011). Money doesn't matter. Praxis: A

Writing Center Journal, 8(2).

Ronesi, L. (2009). Theory in/to practice: Multilingual tutors

supporting multilingual peers: A peer-tutor training course in the

Arabian Gulf. The Writing Center Journal, 29(2),

75–94.

Ronesi, L. (2011). "Striking while the iron is hot." A writing

fellows program supporting lower-division courses at an American

university in the UAE. Across the Disciplines, 8.

Retrieved from http://wac.colostate.edu/atd/ell/ronesi.cfm

Thaiss, C., Brauer, G., Carlino, P., Ganobcsik-Williams, L.,

& Sinha, A. (Eds.). (2012). Writing programs worldwide:

Profiles of academic writing in many places. Fort Collins,

CO: The WAC Clearinghouse and Parlor Press.

Molly McHarg is a writing center instructor and adjunct English

faculty member in Qatar. She has taught at various American branch

campuses in Doha, including Virginia Commonwealth, Georgetown, and

Northwestern Universities. She is president of the Middle East-North

Africa Writing Center Alliance (MENAWCA). She recently completed her PhD

in composition and TESOL at Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

|