|

Maria Elisa Romano

|

|

Julia Inés Martinez

|

Taking into account that feedback is thought to be a

fundamental component of the process of scaffolding language learning,

the implementation of techniques that seek to enhance such interaction

constitute an interesting and necessary focus of current research in

second language (L2) writing. After several years of researching

feedback—and focusing on its different types and agents—we felt the need

to incorporate students’ voices into our research so as to gain a

greater and better understanding of the student-teacher interaction during the writing process. In this respect, self-monitoring stands as a

valuable process to be explored because it involves the participation

of students as the initiators of the process of feedback and subsequent

revision of written texts. When referring to some of the theoretical and

practical principles underlying feedback on writing, Goldstein (2010)

claims that

effective feedback doesn’t start with the text, and isn’t just

about responding to texts; it starts with the student, responding to the

student, what the student wants to accomplish, what the student needs,

and ultimately about teachers and students communicating with each

other. (p. 76)

Our purpose here is to briefly describe a research project

conducted in the Lengua Inglesa II chair at Facultad de Lenguas,

Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (Argentina), that aims to explore the

implementation of self-monitoring as part of an electronic feedback

cycle and to report an analysis of the results obtained in

2012–2013.1

Self-monitoring

According to Charles (1990), self-monitoring is defined as “a

means of increasing the amount of dialogue over the text for those whose

institutional circumstances do not permit individual editorial

discussions on student drafts” (p. 288). Specifically, it involves

students underlining and annotating their drafts with questions, doubts,

comments, or impressions regarding those items or areas in which they

would like to receive feedback from the teacher. The teacher, then,

responds to this text by focusing on the annotations made by the writer.

In this way, the student is the one who initiates and directs the

process of feedback and subsequent revision.

Self-monitoring has been proven to help students gain autonomy

over their revision process, strike a balance between text-based and

surface concerns, and develop awareness on the importance of the content

and organization of their texts. In a study involving EFL university

students in Eastern China, Xiang (2004) discovered that training in

self-monitoring was an effective way of implementing written feedback

inasmuch as it led students toward becoming more critical readers of

their own texts and encouraged them to be more receptive to their

teacher’s feedback, as this was based on their own concerns and on the

main problems they had encountered while writing. As regards

improvements in the quality of their texts, it was shown that more

proficient writers seemed to benefit from this technique more than less

proficient student writers or low achievers, who tended to focus on

surface aspects of their texts. However, in an earlier study, Cresswell

(2000) pointed out that specific training involving awareness raising,

modeling, and evaluation previous to the actual application of

self-monitoring techniques improved students’ ability to pay attention

to the content and organization of their texts. On the basis of the

above-mentioned studies, we decided to explore the implementation of

self-monitoring on the writing of undergraduate students of English as a

foreign language.

Methodology

Three teachers and five intact groups of students of

LenguaInglesa II participated in this study during 2012 and 2013.

LenguaInglesa II is a course in the second year of the undergraduate

programs on EFL at Facultad de Lenguas, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba,

in Argentina. Given the above-mentioned studies on self-monitoring

(Charles, 1990; Xiang, 2004), it was necessary to provide students with

appropriate training prior to the implementation of this type of

student-initiated feedback. Therefore, a whole class period (80 minutes)

was devoted to the introductory session, during which students were

introduced to self-monitoring and the teacher provided examples with the

aim of modeling the technique and showing the type and scope of the

annotations that might be used (questions regarding both language and

content, doubts related to the organization of the text, etc.) and how

these could be inserted in the text by means of the comment function in

Microsoft Word.

After becoming familiar with the basic characteristics of

self-monitoring, students were given instructions for a writing

assignment that was related to the topics being dealt with in class and

that involved the self-monitoring technique—that is, making annotations

on their texts as a way to initiate feedback. They were asked to submit

their annotated texts by e-mail following a set of guidelines normally

used in the course. The teachers provided feedback on the first drafts

by responding to the annotations and, if necessary, by also providing

feedback on other aspects of the text that they thought needed to be

revised.2 Finally, students handed in a second

and revised version of their texts. The whole procedure (that is,

training and implementation of self-monitoring) lasted approximately

four weeks, a period of time quite similar to the amount necessary to

carry out the regular indirect feedback process used during our annual

course.

Results

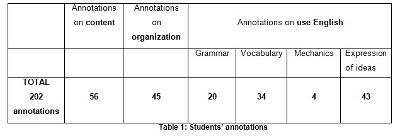

In the first stage of the research project, we

classified and analyzed the annotations students made on their drafts

following the taxonomy proposed by Xiang (2004). Annotations were

classified into three main categories: content, organization, and form

(use of English). Taking into account the specific instructional context

and our own pedagogical concerns, we decided to further classify

annotations on form depending on whether they referred to grammar,

vocabulary, expression of ideas, or mechanics (spelling and

punctuation).

Of the 259 texts collected, only 88 (33.97%) had annotations;

the remaining 171 texts were submitted with no annotations at all. That

is, 66.02% of the students who participated in this study decided not to

insert any comment, question, or doubt in their drafts. From the 88

texts that did include annotations, we collected a total number of 202

annotations. The classification of those annotations is shown in Table

1 (click to enlarge).

Fifty-six (27.72%) of the annotations were identified as

annotations on content. Some examples illustrating the type of

annotations found include the following: “I was not sure if this

sentence is off the point,” “Does this example illustrate the previous

idea?,” and “Shall I paraphrase the meaning to include the idea it

represents?”

Annotations regarding organization amounted to 45, which

represented 22.27% of the total number of annotations. In this category,

some of the comments and/or questions presented by students include

“I'm not sure this transition signal is useful for this type of essay. I

try to show that first I’m going to discuss causes and then the

effects” and “Is the order of ideas correct here? Or should I mention

cause 1—effect one, cause 2—effect 2 for the summary?”

Half of the annotations analyzed (50%) belong to the category

“use of English.” Out of 101 annotations found in this category, 34

addressed vocabulary issues and 43 focused on expression of ideas.

Examples of the former include “Is this word used correctly in order to

refer to the consequences?” and “Is it okay to use phrasal verbs like

this in this kind of writing?” As to expression of ideas, recurrent

annotations were of this sort: “Is it too informal? How could I express

this better?” and “Is this a correct expression?” Of the remaining

annotations, 20 were about grammar, such as "Is this correct, or should I

use other Tense?,” and 4 about mechanics, such as “When I include a

quote from the story, should I use contractions as in the original

text?"

Final Remarks

One of the most outstanding results in this stage of the

research project is the low percentage of students who actually used

self-monitoring as part of the revision and feedback process. It is

quite striking that, given the opportunity to initiate the feedback

dialogue, more than half of the students opted not to do it.

Retrospective interviews are currently being analyzed to look into the

reasons underlying this tendency.

When looking at the most frequent annotations, it is

interesting that a considerable percentage (50%) were on content and

organization, a finding concurrent with the results of previous studies

(Charles, 1990; Chen, 2009; Cresswell, 2000; Xiang, 2004). Although more

research is definitely necessary, it seems that self-monitoring may be

an effective technique to encourage critical reviewing of global aspects

of ongoing texts, which tend to be disregarded by foreign language

learners.

As regards annotations on the use of English, the most frequent

doubts and/or concerns had to do with vocabulary and expression of

ideas rather than with grammar or mechanics. This focus on lexical

aspects of the language seems to characterize foreign language learners’

revision (Ferris, 2003), especially in academic contexts, such as the

one in which this study was carried out.

To summarize, self-monitoring appears to be an interesting

revision technique to promote autonomy and critical self-evaluation as

well as to gear students’ attention to global aspects of their

developing texts. There seem to be, however, some cultural, attitudinal,

and contextual factors that prevent many students from getting involved

in this type of student-initiated feedback.

Notes

1. A preliminary version of this article was presented at the I

JornadasNacionales, III Jornadassobreexperiencias e Investigación en

Educación a Distancia y Tecnologíaeducativa en la UNC, Universidad

Nacional de Córdoba, March 14–15, 2013, by M. E. Romano, J. I. Martínez,

and A. de los Canavosio.

2. The type of feedback given in this instance was the same

type of feedback used all throughout the academic year (explicit

indirect feedback), which is a type of feedback that has proved to be

effective for this specific undergraduate course. The fact that

self-monitoring is complemented with teacher-initiated feedback has to

do with the characteristics and objectives of this particular course and

the broader institutional setting. In addition, and as proposed by

Charles (1990), the main reason why self-monitoring may be accompanied

by other comments from the teacher is to signal sections/areas which may

cause trouble to the text’s intended audience.

References

Charles, M. (1990). Responding to problems in written English

using a student self-monitoring technique. ELT Journal,

44, 286–293.

Chen, X. (2009). “Self-monitoring” feedback in English writing

teaching. Research in Theoretical Linguistics, 3(12), 109–117.

Cresswell, A. (2000). Self-monitoring in student writing:

Developing learner responsibility. ELT Journal, 54,

235–244.

Ferris, D. (2003). Response to student writing:

Implications for second language students. Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum.

Goldstein, L. (2010). Finding “theory” in the particular: An

“autobiography” of what I learned and how about teacher feedback. In T. Silva & P. K.

Matsuda (Eds.), Practicing theory in second language

writing (p. 72-90). West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press.

Xiang, W. (2004). Encouraging self-monitoring in writing by

Chinese students. ELT Journal, 58, 238–246.

María Elisa Romano is a teacher of English and holds

an MA in English with a focus on applied linguistics. She works as a

full professor of Lengua Inglesa II at Facultad de Lenguas, Universidad

Nacional de Córdoba. She has participated in several research projects

on foreign language writing, especially on revision and

feedback.

Julia Inés Martínez is a teacher and translator of

English, and holds an MA in English with a focus on Anglo-American

literature. At present, she works as a full professor of Lengua Inglesa

II at Facultad de Lenguas, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, in

Argentina. She has participated in several research projects on

EFL.

|