|

Reading Mitchell Goins’ (2015) article

about written corrective feedback reminded me of the struggle to

provide individualized feedback to students that is both effective and

manageable. As Goins stated, metalinguistic written corrective feedback

can provide the benefits of both direct and indirect feedback. Students

are given clear instruction about the type of error made and how to

correct it while still being required to process the error and correct

their own work. However, teaching one writing issue to a whole class

does not provide any differentiation, and as I read, I kept thinking

about the following question: How can we meet our students’ needs while

providing effective individualized support without overburdening our

teachers?

In this article, I describe how I developed a strategy that

incorporates both targeted mini-lessons and a whole-team approach to

support the individual language needs of second language writers. The

students I describe are emergent writers who are beginning to express

themselves and take risks in their writing, providing opportunities for

instruction that targets their individual needs. My approach to

providing written corrective feedback has evolved over a number of years

from my experience teaching adult English language learners to my

current position supporting 300+ Prekindergarten to Grade 12 English

language learners in 20 schools in Saskatchewan, Canada. I also read

research in this area, engaged in discussions with other teachers, and

experienced a lot of trial and error. Through my work in this area, I

have found this strategy to be most effective with students from Grades 4

and older whose English skills are midbeginner and higher.

Providing Feedback

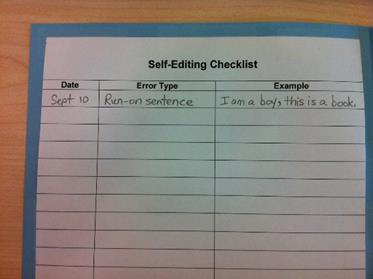

Each student has his or her own journal of lined pages. The

first page of the journal is the self-editing

checklist, a record of the error types the student has learned

how to correct. As an error type is identified, the

teacher records it on the checklist. Each error type is recorded once,

using the length of time between entries in the date column as an

indication of how long the student works on any particular error type.

Once the student achieves approximately 80% success self-correcting for

that error, the teacher selects another error type on which the student

needs to focus.

Figure 1. Self-editing checklist

The bullet points below describe the steps used in this journal.

-

The teacher reads the student’s writing, identifying a

variety of error type patterns, and then selects one on which to focus. I

recommend selecting an error that reflects a grammar pattern or rule

rather than writing style and beginning with basic rules that are easier

to teach (e.g., capitalization, subject-verb agreement, use of verb

tenses). The teacher uses a highlighter to highlight the places in the

student’s text where the error occurred. No

correction is made at this point.

-

The student is then asked to reflect on their writing first,

and then they share their reflections with either the teacher or the

whole class. Students think about the following questions: Why do you

think the teacher highlighted those areas? Can you see a pattern? What

is it? How can it be corrected? It is surprising how often the students

can identify the error from the highlights.

-

Once the error type is identified, the teacher provides a

short mini-lesson in class on how and why the correction is made. New

material should be used for this instruction, not the student’s journal

entry, and the lesson should be 10 minutes or fewer. If it requires more

time, teachers can scaffold the instruction into smaller parts and

teach each successive step as the previous steps are learned. I

recommend using new material for mini-lesson instruction for two

reasons: to avoid student embarrassment from seeing their errors shared

with the class, and to encourage engagement as each student applies what

he or she has learned to his or her own writing.

-

With each successive journal entry, the student is expected

to self-correct the error types already learned, as noted on the

checklist. Once the student achieves an 80% success rate, the teacher

selects a new error type on which to focus. Eventually, the student may

make fewer errors which need correcting. At this point, the teacher may

begin to teach strategies for improving the complexity and quality of

the student’s writing, continuing the highlighting and mini-lesson

structure of instruction.

Managing Mini-Lessons

In order to make the delivery of mini-lessons manageable,

teachers should aim to group their students by the writing issue they

need help with. For instance, students who need to edit for run-on

sentences receive separate instruction from those who are working on

subject-verb agreement. These groups are fluid and change as needs are

identified and addressed. Grouping students in this way allows the

teacher to provide customized instruction to groups of students rather

than separately to each individual student. Once in while, a student may

require individual instruction, but to date, this has rarely occurred.

Teachers can also deliver mini-lessons by delivering one

mini-lesson per day and/or spreading the group lessons out over a few

days. In my class, for instance, this means that the rest of the class

only has one 10-minute block for independent reading or work rather than

a series of blocks throughout one lesson. Teachers in my schools have

also experimented with workstations, computers, and the flipped

classroom approach to deliver customized lessons, providing

differentiated instruction for independent learners and creating

opportunities for teachers to work with students who require more

support.

Final Reflections

It is important for teachers in other subject areas to support

the student’s writing improvement by working collaboratively. When I was

a classroom teacher, I was responsible for the journal writing process

described above, and my colleagues supported this process in their

subject areas by using the self-editing checklist as a guide for

assessing the student’s work. Each subject-area teacher would assess and

correct the student’s work for content, but when they assessed

students’ English language use, the teachers used a highlighter and only

highlighted the errors that matched the items listed on the student’s

self-editing checklist. In this way, they were not teaching new grammar

or writing issues, but encouraging the student to use their prior

knowledge to improve their writing in all subjects. Students have stated

that they appreciate being able to focus on one issue at a time,

avoiding the red ink that used to cover their assignments. Because they

have to reflect on their own writing throughout the process, they become

more mindful while writing. Students who require direct language

instruction receive it, and the instruction is focused on their

individual needs.

While we feel this strategy has been successful, my colleagues

and I did struggle somewhat with how to share the self-editing

checklists amongst the staff. We tried using an online sharing board,

sending updates by email, and even posting notices in the staffroom.

Each approach proved cumbersome, so we decided each student would be

responsible for sharing their updated checklists with their teachers

when submitting an assignment. Another struggle was that some colleagues

have participated more actively than others. Many teachers chose to

only check the English in some, rather than all, of the assignments they

received, and some subject-area teachers were also not comfortable

teaching English grammar, so they appreciated leaving the mini-lessons

to someone who is. It became apparent to me that participation and

success were only possible if I was willing to differentiate for both

the needs of my colleagues and my students.

Despite these minor challenges, this process of providing

individualized written corrective feedback has evolved into a strategy

that can be used with all students, whether they are English language

learners or native English speakers, and in all subject areas to support

the development of student writing. It should be noted that teachers

who plan to implement a school-wide team approach with this writing

strategy should provide their colleagues with an overview of how this

strategy works and clear instructions as to what their role is. Working

as a team to help our students improve their writing appears to be

meeting a need in both our students and staff.

Reference

Goins, M. (2015). Written corrective feedback: Strategies for

L2 writing instructors. SLW News. Retrieved from http://newsmanager.commpartners.com/tesolslwis/issues/2015-10-07/3.html.

Liz Rowley is an EAL consultant for the

South East Cornerstone Public School Division in Saskatchewan, Canada.

She earned her master’s degree in TESL/TEFL from Birmingham University

in the UK, and she has taught in Canada, England, and South Korea. She

currently supports EAL students, their teachers, administrators, and

families across the school division. |