To date, American Sign Language (ASL) dictionaries have

generally provided word search from English to ASL. Deaf children could

not look up vocabulary meanings according to their own primary language,

ASL. They could not look up meanings of an ASL word they saw and they

could not look up English counterparts to an ASL word they knew.

Therefore, Deaf children have had to rely on adults for definitions if

they recognized the ASL word but not the English vocabulary. As well,

parents of Deaf children have had no way to search a sign they saw for

which they did not know the meaning.

Furthermore, all print dictionaries are frozen with pictures

and ASL is a spatial language that cannot be fully represented in book

format. These picture dictionaries provide limited meta-linguistic

awareness of ASL features. Children’s ASL dictionary access has depended

on the philosophy and finances of natural gatekeepers (teachers,

parents, medical professionals, principals). Until now, there has been

no ASL-based dictionary designed specifically to look up words in

animated ASL to capture children’s fascination and make it

fun.

We, as codirectors of the Deaf Culture Centre, through the

Canadian Cultural Society of the Deaf (CCSD), determined to create the

first children’s animated ASL dictionary. The dictionary was to be

freely accessible on the Web.

FORGING ALLIANCES TO ACTUALIZE THE VISION

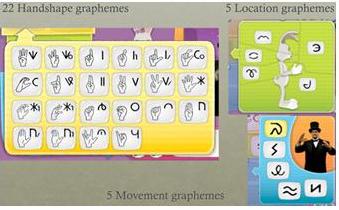

We had attended a workshop by Dr. Sam Supalla from the

University of Arizona in 2002 on ASL graphemes that had a huge impact on

our thinking related to ASL word search and how it could be done. Dr.

Supalla and his team had explained an ASL-phabet,

[1] or grapheme system, that

delineated the features that make up ASL words. We envisioned an

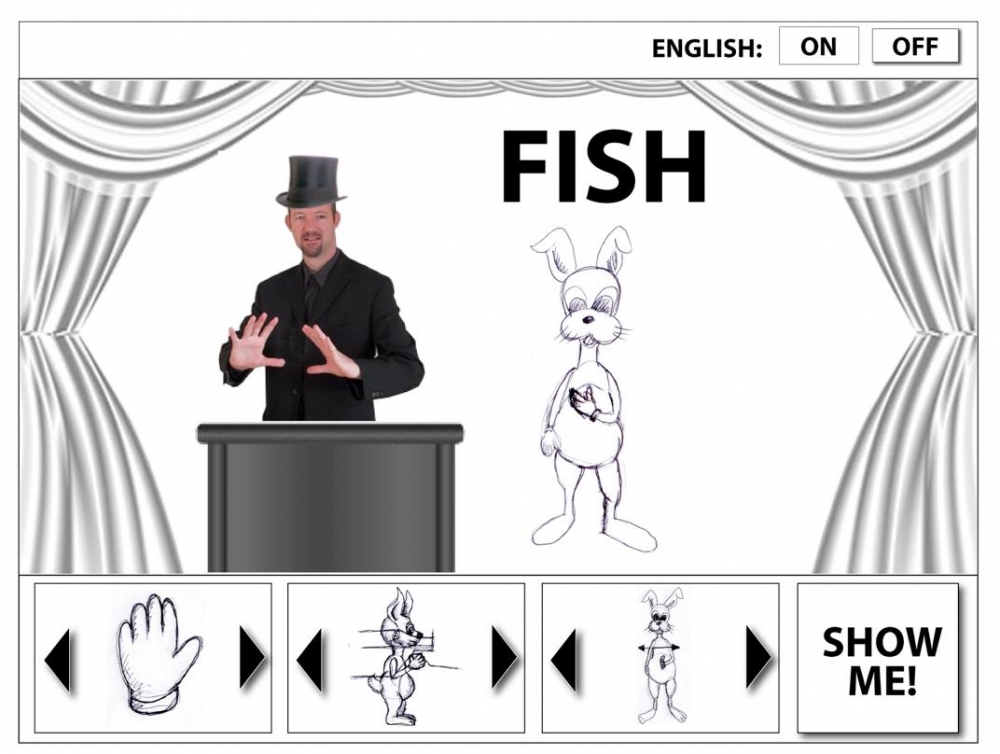

animated ASL dictionary for children that provided the ability to search

ASL words based on features, handshape, location, and movement (see

Figure 1). Children could scroll through the features of ASL (much like

the pictures on a slot machine) to select the features of the ASL word

they needed. It would alleviate the cumbersome nature of leafing through

pages of a text to find the feature needed and would be

three-dimensional―a critical feature for an ASL dictionary (see Figure

2).

In 2007, we attended the World Federation of the Deaf

Conference in Madrid, Spain, where we were impressed with the precision

and style of Deaf award-winning animator Braam Jordaan from South

Africa.

We had previously collaborated with the new-media production

company, Marblemedia Inc., on the award-winning deafplanet.com

educational TV series and Web site. We were confident with their skills

in educational Web development. We therefore forged a tri-country

alliance, with linguistics consultation from the United States,

animation from South Africa, and dictionary content and Web site

structure from Canada.

Figure 1. ASL word search by handshape, location, and movement.

Vision by Anita Small and Joanne Cripps, CCSD (2002)

Draft sketch by marblemedia Inc. and CCSD (2008)

Figure 2: ASL-phabet1 handshape (yellow), location (green) and movement (blue) grapheme selection on the final dictionary prototype (2009)

FUNDING AND PERMISSIONS

With $147,700 in funding in 2008 from the Inukshuk Wireless

Learning Plan Fund, we embarked on developing a prototype that included

100 words, multiple definitions, use in sentences, and English

translation. This prototype for young children in junior kindergarten

(JK) to grade 2 would serve as the template for dictionary testing and

expansion.

We received permission from Dr. Sam Supalla to use the

ASL-phabet grapheme system, his consultation, and The Resource

Book (2009). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Co. gave

permission to use and adapt word definitions from The American

Heritage First Dictionary (2003). We, CCSD, held the copyright

for the Canadian Dictionary of ASL (2002), which we

used for reference to adult definitions of signs in a printed

text.

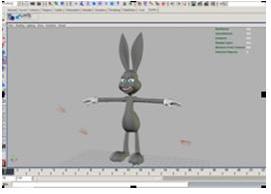

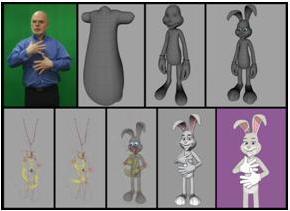

Figure 3. First draft of animated character, “scary rabbit,” by Braam Jordaan.

Figure 4. Refined “sweet rabbit” by Braam Jordaan. Inserted

into animated dictionary structure by Marblemedia Inc. & CCSD.

Figure 5. Final rabbit signing “breathe” by Braam Jordaan.

Figure 6. Final animated dictionary structure by CCSD and Marblemedia Inc.

Graphic design by Marc Keelan-Bishop.

VOCABULARY MODEL DEVELOPMENT

We envisioned an animated character for the signing “model” and

a human character to define and use the word in sentences. We needed to

think of a natural animated character/human pair. The animated

character required large clear hands for signing. We selected an

animated rabbit and a magician for the human character. We thought this

was a pair that young children in JK to grade 2 would relate to.

The animated character went through several renderings. It

eventually became a sweet rabbit suitable for young children (see

Figures 3 and 4). The animator emphasized the rabbit’s signs with stars

to trace the movements (not seen in figures).

VOCABULARY SELECTION

We used random selection (every third word) from The

Resource Book to obtain 300 words to define. Master ASL

instructor Mario Pizzacalla signed all 300 words on film. We sent video

clips of 100 words to South Africa to be transformed by Braam into

animations (see Figure 5). All words selected were cross-referenced fromThe American Heritage First Dictionary (2003)to

ensure appropriateness for this young age group.

Teachers from the Ontario Provincial Schools for Deaf students

wrote out the graphemes to be used in the dictionary for the vocabulary

selected. Dr. Sam Supalla reviewed all grapheme representations of the

words.

PRODUCTION OF DEFINITIONS

There is no one-to-one correspondence between ASL and English

semantics. For example, the English word run has

multiple definitions and multiple ASL signs. As well, one ASL sign may

have two or more definitions and two or more English words as in miss/guess.

Therefore, adaptation and additions of dictionary definitions

from The American Heritage First Dictionary (2003)

and Canadian Dictionary of ASL (2002) were critical.

ASL/English interpreting students developed the initial adaptations of

the English word definitions. We (a hearing sociolinguist and deaf

community leader, respectively) reviewed the ASL definitions along with a

Deaf adult child of Deaf parents and Deaf ASL linguist.

It should also be noted that there are homographs in ASL,such

as act and address, which have the

same grapheme representation (Supalla, e-mail correspondence, 2009)

just as there are homographs in English, such as wind

in “blow wind”and “wind the clock.”

Multiple definitions, lack of one-to-one correspondence of

vocabulary in ASL and English, and homographs all had to be taken into

account in the dictionary’s structural design.

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION

To evaluate efficacy of the animated dictionary prototype, we

pretested the prototype Web site for usability and outcomes at three

bilingual schools for Deaf students. We tested the site with 52 students

and 14 teachers in nine classes from JK to grade 4. We used

ethnographic methodology including observation, field notes, and teacher

report throughout one week in November 2009.

RESULTS

Usability

We discovered that students liked the signing title and loved

the rabbit and magician. Many users asked for a full-screen version. The

grapheme word list is not currently in order. All English words begin

with a capital letter. This is confusing to students. Some feedback

showed confusion on the “1,2,3” boxes. Some students clicked on the

numbers rather than the boxes beside them. This was improved on by

highlighting the box. Students did not seem to know how to “get out” of

an action or reset the tool for a new word. This was improved on by

creating an “x” box to exit from an action. It was suggested that we

should place the “play” buttons for the rabbit and the magician close to

the characters.

In all cases, the tool was used much more effectively after the

teacher had tried it first and could problem-solve with the students.

Students need instruction on graphemes for easy use. Students liked the

introduction, but many wanted to see an additional introduction to what

the graphemes are as well, and why they are important. There is also a

need for a teacher-training module with the ASL grapheme explanation.

Some younger students found there were too many buttons and were

distracted by them. This was improved on in the help section by removing

the multiple arrow buttons and replacing them with highlighted

sections.

The site was thought to be useful up to approximately grade 8.

Some users wished they could have a keyboard to type graphemes to select

the ASL words. Initial comments included “hard” and after 15 minutes

included comments such as “cool” (JK), “he’s cool!” (grade 1), “I love

it!” (JK to grade 4, teachers, teacher aide) “love it!” (teacher), and

“This is fantastic!” (teacher).

Learner Outcomes

Many students demonstrated the use of ASL word imitations such

as accept, strange, same, wrong, again, never, agree, and scratch when they were using the

dictionary. Students repeated definitions to their

teachers and to the researcher. They displayed meta-linguistic skills

and independent research skills, learning the search strategies within

15 minutes. Students were able to maintain their focus on the animated

dictionary from 15 to 50 minutes.

FUTURE PLANS

We intend to expand the animated dictionary of ASL to 1,500

words, which is the norm for most children’s dictionaries designed for

this age group. The expanded animated dictionary of ASL will include

cross-references. In other words, one ASL sign will have multiple

definitions and different English words when applicable. Similarly, one

English word will have multiple definitions and multiple ASL signs when

applicable. ASL and English will remain absolutely separate in the

dictionary Web site structure. The option of having a voice-over to hear

the English interpretation of the ASL for hearing users will be added

to the Web site. A parent and teacher guide explaining graphemes will be

added to the Web site and ASL-phabet training for teachers will be

provided with support from grant funding in the future. Further testing

of the expanded Web site for effectiveness as a resource in both first

and second language acquisition of both ASL and English will be

explored.

REFERENCES

Canadian Cultural Society of the Deaf Inc. (2002). Canadian Dictionary of ASL (C. Bailey and K. Dolby,

Eds.). Edmonton, Alberta: University of Alberta Press.

Editors of the American Heritage Dictionaries. (2003). The American Heritage First Dictionary. Boston, MA:

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

Supalla, S.J. (2009). The resource book.

Unpublished manuscript. Tucson: University of Arizona.

Supalla, S., Wix, T., & McKee, C. (2001). Print as a

primary source of English for deaf learners. In J. Nicol & T.

Langendoen (Eds.), One mind, two languages: Studies in

bilingual language processing (pp. 177-190). Oxford, England:

Blackwell.

Anita Small, MSc, EdD, Deaf Culture Centre and

University of Toronto Scarborough, Department of Humanities –

Linguistics, and Joanne Cripps, CYW, Deaf Culture Centre and Ryerson

University, BA candidate, Department of Politics and Public

Administration

[1] Permission granted by Dr. Sam Supalla for

citation of ASL-phabet.