|

Pakistan, a Federal Parliamentary Islamic Republic with more

than 176 million people, consists of four Provinces (Balochistan, Khyber

Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab, and Sindh) and four federal territories (Islamabad

Capital Territory, Federally Administered Tribal Areas [FATA], Azad

Jammu and Kashmir, and Gilgit-Baltistan; (Government of Pakistan, 2011).

Classroom Map of Pakistan

Pakistan is a heterogeneous country with many religious,

cultural, linguistic, and ethnic groups and is socioeconomically,

educationally, geographically, and ecologically diverse. The country is

one of 19 with high linguistic fractionalization, one of 11 with high

fragility and conflict levels, one of 34 less developed with large rural

population (Pinnock, 2009) and the 145th of the 187 countries with low

human development (UNDP, 2011). These figures present a tremendous

asset, an opportunity, and a necessity for the republic to practice

inclusion, tolerance, and acceptance. However, this very diversity and

the ways it has been dealt with have often challenged the country, which

suffers from historical hostility between and among groups resulting in

state fragility, conflict, and insurgency.

Although Article 25A of the 18th Constitutional Amendment

(2010) calls for free and compulsory education for all 5- to

16-year-olds and puts the sole responsibility for this on the state, in

2012, 23% (rural) and 7% (urban) 6- to 16-year-olds were not in school

(ASER, 2012, p. 8). One in 10 out-of-school children live in Pakistan

and by 2015 there will still be more than six million out-of-school

children in the country (UNESCO, 2011, p. 42).

Of those enrolled in school very few are actually learning.

Student achievement is falling significantly below the standard

curricular levels, with more than 50% of fifth graders not able to cope

with second-grade basic literacy and numeracy skills (ASER, 2012). For

example, in 2012, more than 64% of fifth graders in Balochistan were not

able to carry out a third-grade-level division sum and more than 11% of

10th graders in FATA were not able to read a second-grade story in Urdu

or Pashto. Learning levels are “alarmingly” different between males and

females across all socioeconomic levels, with the exception of girls

who come from the richest income group (ASER, 2012, p. 22). Illiteracy

levels in the country are dire and the most vulnerable populations are

children who are linguistically diverse (UNESCO, Misselhorn, Harttgen,

& Klasen, 2010).

In contrast to this extreme education poverty, the people of

Pakistan have a rich linguistic repertoire with about 61–72 languages

spoken in the country. A majority of Pakistanis speak or understand more

than two languages (Lewis, 2009; Rahman, 2010). About 44% of the

population speaks Punjabi, followed by Pashto (15%), Sindhi (14%),

Seraiki (10%), Urdu (7.6%), and Balochi (3.6%). Other major languages

spoken are Hindko, Kashmiri, Khowar, Kohistani, Brahui, Baryshaki,

Arabic, Dari, Persian, and Turkic.

Linguistic map of Pakistan; Source: Fred Bolor, 2009

For historical, political, and other reasons Urdu has prevailed

as the national language and along with English—the former colonial and

now official language—have been promoted in schools. Urdu is the mother

tongue of only about 8% of the population, yet it is widely used

nationwide, although in some provinces “there is a certain degree of

hostility towards the national language” (Coleman & Capstick,

2012, p. 15). The proponents of teaching in Urdu argue that one language

is essential to maintaining national unity, and this issue has been an

important contributing factor to the Sindhi nationalism and the Balochi

insurgency.

Unfortunately, 91% to 95% of the country’s children have no

access to education in their mother tongue, making Pakistan one of 44

countries facing the same issue (Coleman, 2010; Pinnock, 2009; Walter,

2009).

Language Policy and Practice in Education

Since 1947, language-of-instruction mandates have changed many

times—all failing to formulate a clear, sustainable, and effective

policy. The most recent national education policy was developed in 2009.

This policy addressed the issue of language of instruction, suggesting

that English be taught as a subject from first grade onward and Urdu and

one regional language be included in the curriculum. Starting in fourth

grade, science and mathematics should be taught in English only.

The policy does not take into consideration that the vocabulary

and cognitive processes involved in teaching and learning a language as

a subject with actually teaching and learning a content area through a

second language differ greatly in intensity, vocabulary, and methodology

(Ball, 2011; Chamot & O’Malley, 1986; Coleman, 2010; Coleman

& Capstick, 2012; Fleming, 2006). It makes no clarification

about the medium of instruction in primary schools and gives no

guidelines for policy implementation to the provincial authorities. And

as the power has been returned to the provinces, making them responsible

for policy formulation and sector financing, only sporadic and

unsystematic efforts across the provinces to develop

language-of-instruction policies have been observed.

Thus, in Sindh, Sindhi is the only provincial language that is

used in lower administration, judiciary, and education. Yet, although

the medium of instruction in public schools is Sindhi (97%), Urdu (2%),

and English (1%; ASER, 2012, p.18), linguistically diverse children in

several areas of the province are still denied a meaningful education by

the exclusion of their mother language in school (Rafiq,

2010).

In Punjab, the country’s most populous province, with about 100

million people, the popular but unfortunate English Language Initiative

emerged recently and has been implemented in public schools. The medium

of instruction in public schools is English (50%) and Urdu (50%; ASER,

2012, p. 18), textbooks are now printed in English and primary and

secondary teachers are urged to use it as the medium of instruction.

Yet, although the majority of teachers are not fluent in English or do

not speak it at all, it is expected that after two weeks of language

training, they should be able to teach effectively in English to

children whose mother tongue is Punjabi or another provincial language.

In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa there is greater awareness and

appreciation of the diversity of the provincial languages and of the

benefits of instruction in the mother tongue. The government, with the

support of development partners, initiated an effort to standardize the

alphabets of Seraiki, Khowar, Kohistani, and Hinko while involving local

communities, experts, poets, writers, religious leaders, and other

stakeholders. This effort led to the Mother Tongue Education Bill (2011)

according to which, from 2012–2013 and in the areas they are spoken,

the regional languages are to be taught as compulsory subjects in Grades

1–7 and by 2017–2018 in Grades 8–12. However, this policy has not been

implemented as intended. The medium of instruction is Urdu (66%), Pashto

(30%), and English (3%; ASER, 2012, p. 18).

In Balochistan, although Balochi is spoken by the majority of

the population in the province, it is not the official language, and

Urdu is the medium of instruction in 100% of the government schools

(ASER, 2012, p. 18). Balochi is taught at the University of Balochistan

in Quetta, at the Balochi Academy, and is used in radio, television, and

publications. It was introduced in the 1990s as the language of

instruction in primary schools, but the policy was short-lived primarily

because of negative attitudes toward the language and disagreements on

its proper orthography and use (Jahani, 2004). In FATA, government

schools use Urdu (80%), Pashto (17%), and English (2%); in Gilgit

Baltistan, Urdu (68%) and English (32%); and in Azad Jammu and Kashmir,

Urdu (97%) and English (3%; ASER, 2012, p. 18).

Language of Instruction and the Curriculum

In Pakistan the curriculum and language of instruction vary

depending on the type of school, the province, or federal territory. The

elite private schools, the schools run by the armed forces, and many of

the low-cost private schools use English. Of the 41 home languages

recorded by ASER, only Sindhi, Urdu, Pashto, and English are used in

government schools (ASER, 2012; Coleman & Capstick, 2012). The

religious schools, the Madrasas (or

Madaris) use varying media, including Arabic and are usually

the schools of the very poor.

The last national education curriculum was developed in

2006–2007 and set language learning standards for Urdu and English but

not for other Pakistani languages. It was developed under the auspices

of the Federal Ministry of Education, Curriculum Wing (now abolished

with the 18th Amendment) in collaboration with UNESCO, the Education

Sector Reform Assistance Program, experts, educators, and other

stakeholders. It has been largely debated and although initially adopted

by the provinces, it will eventually be abandoned as a consequence of

the devolution.

The 2006–2007 curriculum claimed to be focused on student

learning outcomes and based on the principles of inclusion,

nondiscrimination, tolerance, acceptance of diversity, gender equity,

responsible citizenship, promotion of peace, and avoidance of extremism,

war, and radicalization. However, there is a mismatch between its

principles and its practices. Textbooks do not reflect the colorful

mosaic of the diverse languages, cultures, or religions of the country.

Lessons portray only Muslim heroes and do not include minorities or

women heroes, artists, scientists, and poets. Women and girls are

presented assuming traditional roles at home. Many lessons are about

nationalism and glorifying wars, and very few link religion,

nationalism, and peaceful coexistence.

The majority of first- and second-grade textbooks are

unsuitable for young children—especially those whose mother tongue is

different from the language of instruction. They have long passages,

complex texts and layouts, and the texts written in Urdu use the

Nasta-liq script (the “cursive” nonlinear form of Arabic), which makes

it very difficult for young learners to become readers. This puts

children from linguistically diverse and poor households at a great

disadvantage.

First Grade Students Copying from The Board

Literacy attainment becomes more difficult when schools have

very limited resources. Teacher and student absenteeism hits government

schools like a plague. It is estimated that about 13% of teachers and

18% of students (in Sindh 40%) are absent on a daily basis (ASER, 2012,

p. 8). “Ghost teachers,” teachers no one has ever seen, are on the

payroll; corporate punishment is present, and, in some cases, children

suffer serious or fatal injuries as a result. In some areas,

parents—especially those of girls—are reluctant to send their children

to school because they find the curriculum irrelevant to their own

culture, the school has no boundary walls or sanitation facilities, or they fear

that extremist religious groups may threaten their families’ lives and

safety.

School Fountain

In Punjab, the top-down monitoring system implemented by the

government to monitor schools’ compliance with existing mandates is

called the Roadmap (see picture below).

This approach helped improve several quantitative indicators,

such as teacher presence in class, preparation of daily lesson plans,

and dissemination of textbooks. However, a heavier emphasis must be

placed on qualitative indicators such as lesson quality and relevance,

language of instruction, and effectiveness of instruction and

assessment. Submitted lesson plans, for example, are done for the most

part to pass inspection requirements without much substance or

pedagogical appropriateness.

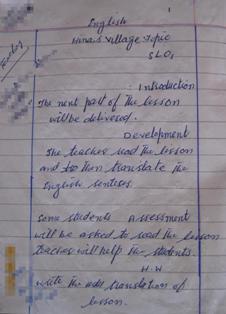

Approved Lesson Plan

Therefore, monitors visiting the schools to record compliance

must be knowledgeable and well-trained educators to adequately evaluate

lesson plans and classroom practices.

Conclusion

The development of specific policies and practices to address

the issues of language of instruction and effective teaching for the

poor is critical to engage and retain more children in school who are

actually learning, as well as in tackling the education emergency in

Pakistan. Individuals’ right to education can be actualized when

policies are based on learning theory and research, and are designed not

for their popularity but for their effectiveness and sustainability.

The education of culturally and linguistically diverse children must be

considered from a holistic point of view, actively involving parents,

families and communities, all in the context of Pakistan’s

sociocultural, ethnic, economic, and political complexity as well as the

security situation in the country.

Tackling illiteracy and teaching children how to read and write

in the primary grades in a language they speak and understand must be

education’s primary focus. Instructing children in “broken” English from

teachers who do not speak the language themselves only perpetuates

illiteracy’s vicious cycle and gives false hopes to millions of families

who dream of a better life for their children. Parents and stakeholders

must be made aware that instructing children in a language they speak

and understand will not only improve the latter’s knowledge in the

content areas; it will also help them learn other languages (e.g., Urdu,

English) efficiently and effectively (Patrinos & Velez, 1996).

Addressing issues related to quality of teaching, such as lack

of accountability, teacher absenteeism, and systemic corruption in

education, and creating safe and child-friendly schools for all girls

and boys are central to any educational reform in Pakistan. Teacher

education and professional development must focus on improving

instructional and assessment practices for culturally and linguistically

diverse students, and a comprehensive education policy must address the

language of instruction as one of the most essential contributors to

children’s learning in this challenging country.

References

ASER. (2008). Annual status of education

report (rural): ASER-Pakistan 2008.

Retrieved from http://www.aserpakistan.org/document/aser/Aserpak2008.pdf

ASER. (2012). Annual status of education

report (national): ASER-Pakistan 2012.

Retrieved from http://www.aserpakistan.org/document/aser/2012/reports/national/National2012.pdf

Ball, J. (2011). Enhancing learning of children from

diverse language backgrounds: Mother tongue based bilingual or

multilingual education in the early years. Paris, France:

United Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organizations.

Chamot, A. U., & O’Malley, J. (1986). A

cognitive academic language learning approach: An ESL content based

curriculum. Wheaton, MD: National Clearinghouse for Bilingual

Education.

Coleman, H. (2010). Teaching and learning in Pakistan:

The role of language in education. Islamabad, Pakistan:

British Council. British High Commission.

Coleman, H., & Capstick, T. (2012). Language

in education in Pakistan: Recommendations for policy and

practice. Islamabad, Pakistan: British Council.

Fleming, M. (2006). The teaching of language as school

subject: Theoretical influences. Strasbourg, France: Council

of Europe.

Government of Pakistan. (2011). Population census

organization. Islamabad, Pakistan: Ministry of Economic

Affairs and Statistics, Statistics Division. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov.pk

Jahani, C. (2004). State control and its impact on

language in Balochistan. In A. Rabo & B. Utas (Ed.), The role of state in East Asia. Stockholm, Sweden:

Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul. Retrieved from http://www2.lingfil.uu.se/personal/carinajahani/jahani-red.pdf

Patrinos, H., & Velez, E. (1996). Costs and

benefits of bilingual education in Guatemala: A partial

analysis (Human Capital Working Paper No. 74). Washington, DC:

World Bank Group.

Pinnock, H. (2009). Language and education: The

missing link. Reading, England: CfBT Education Trust and Save

the Children.

Rafiq, G. R. (2010). Language policy and education in

Sindh, 1947–2010: A critical study. Santa Barbara: University

of California.

Rahman, T. (2010). Language policy and localization in

Pakistan: Proposal for paradigmatic shift. Retrieved from http://www.apnaorg.com/research-papers-pdf/rahman-1.pdf

UNDP. (2011). Sustainability and equity: A better

future for all. New York, NY: Author. Retrieved from http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/HDR_2011_EN_Contents.pdf

UNESCO. (2011). The hidden crisis: Armed conflict and

education. Paris, France: Author. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0019/001907/190743e.pdf

UNESCO, Misselhorm, M., Harttgen, K., & Klasen, S.

(2010). Deprivation and marginalization in education.

Paris, France: Author. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/ED/GMR/html/dme-5.html

Walter, S. (2009). Language as a variable in primary

education. Arlington, TX: SIL International.

Dr. Eirini Gouleta is associate professor of

international education and interim academic program coordinator of the

Multilingual Multicultural Education programs at the Graduate School of

Education, George Mason University, in Fairfax, Virginia. She has work

and research experience in education development and in Pakistan, where

she served as a senior education adviser and team leader for the

provincial delivery of education for the U.K. Department for

International Development. |