|

As instructors, our goal is to help our learners succeed. We

work at honing our teaching practice and improving outcomes for our learners.

Yet, despite our best efforts and often without our realizing, our classrooms

and the interactions between all present in them are sometimes reflections of

the larger macrocultures in which we operate. Particularly in these challenging

times of the COVID-19 pandemic and of systemic racism becoming more apparent to

privileged communities, when macrocultures can be especially harmful to some

students, how do we recognize when we are doing this, and how do we stop? One

tool to help is to work toward creating an interculturally competent classroom

(ICCC).

Interculturally

Competent Classrooms

An ICCC is a transformative environment that

effectively blends TESOL’s 6 Principles® (TESOL International Association,

2018) and Gay’s (2018) components of culturally responsive teaching with

insights gained by careful introspection into one’s own teaching experiences.

The result of this process is a learning environment that is more responsive to

and inclusive of both learners’ needs and the educational expectations placed

on them by external factors, such as the educational context where the teaching

occurs and even the target culture(s) we are preparing our learners for.

Much like

yoga, designing and implementing an ICCC is a practice rather than an end

state. It is an ongoing journey of

understanding our learners, ourselves, how we are privileged, and external

factors that affect classroom interactions. In this article, I share the

path I take toward implementing an ICCC. My practice has evolved as I have

become more aware of my own implicit biases and will continue to evolve as new

situations help me identify cultural blinders for the first time or in new

ways. Following are three major tenets based on the aforementioned 6

Principles, Gay (2018), and personal experience that have guided my journey to

being more culturally responsive as an instructor:

-

Know your learners.

-

Learn about yourself and

develop your own intercultural competence.

-

Bridge the gap between your

learners, yourself, and your curriculum to create conditions for learning.

My goal is that, by

sharing my own journey rather than speaking in purely academic terms, I can

better show how implementing an ICCC is an evolutionary process that can help

all of us become aware of our own biases and privilege regardless of teaching

context.

1. Know Your Learners

Who are my

learners? This simple question (based on Principle 1 of TESOL’s 6 Principles,

2018) can be examined in layers, with each layer revealing ever deeper

constructs of culture and identity:

-

Where are my learners from?

-

Why do they want or need to

learn English?

-

What are their first

languages?

-

Which cultures do they

belong to and identify with?

-

What do they expect to see

in a typical language lesson?

-

What kind of relationship

do they expect between themselves and each other?

-

What kind of relationship

do they expect between themselves and me?

-

What

kind of relationship do I expect between my students and me?

-

How do they define

knowledge?

-

How do I define knowledge?

-

How do they expect

knowledge to be shared?

With each

new question, I uncover another thread of the tapestry that represents each of

my learners and my own assumptions.

Though my

view of these tapestries may perpetually remain at least partially obscured

because of how hard it is to identify deep-seated cultural practices,

understanding who my learners are and what they need is an essential step in

exemplary language teaching (TESOL International Association, 2018; Gay, 2010).

Over my years teaching English as a second language, I have noticed many ties

between my learners even though they may range from being newly resettled

refugees to military students:

-

The majority of my learners

come from collectivist cultures.

-

Several come from

non-Western educational traditions that operationalize education very

differently from my own.

-

Some have arrived with

limited or interrupted formal education but a wealth of practical, hands-on

experiences.

-

Some expect me to share

personal information with them to build community in the classroom.

DeCapua and

Marshall (2011) clarify these ties and how they manifest themselves in the classroom;

these ties often form the starting point for instruction. However, as I get to

know each student and class better, I am better able to tailor instruction to

meet their needs, both educational and individual.

2. Learn About Yourself

and Develop Your Own Intercultural Competence (Gay’s component: become

culturally competent)

In the

ongoing process of coming to know my learners, I have found merely learning

about them to be insufficient. Gay (2018) prescribes becoming culturally

competent: I must also learn about myself and apply the same questions to

myself that I used to only apply to them. For example: In the

ongoing process of coming to know my learners, I have found merely learning

about them to be insufficient. Gay (2018) prescribes becoming culturally

competent: I must also learn about myself and apply the same questions to

myself that I used to only apply to them. For example:

-

What do I expect to see in

the classroom?

-

What behaviors I expect of

learners?

-

What types of activities do

I think will help my students grasp a new concept?

-

How do I measure

success?

-

What do I think constitutes

knowledge?

Without this

introspection, I find myself expecting my learners to adhere to implicit

cultural models of schooling and education based on my own educational models

and the expectations of the programs I teach in (DeCapua & Marshall,

2011; Gay, 2018), with the result that my classroom has been and continues to

be culturally insensitive.

Applying

Byram’s (1997) model of intercultural competence to myself, which includes

applying his ideas of developing critical cultural awareness, staying curious,

working on skills of discovery and interpreting, and increasing knowledge has

helped me to become aware of areas in which I need to grow as a teacher and a

person, thereby helping to foster a classroom that is more interculturally

competent. Some of the following aspects of my own cultural upbringing, when

unrecognized, have contributed to my classroom’s cultural insensitivity:

-

I

come from an individualistic culture where individual accountability is a

cornerstone of education.

-

I

have understood education to mean classifying information into abstract

categories.

-

I

have viewed the written word as king of communication.

-

I

come from a tradition where personal information is only shared in rare

instances in the classroom or the workplace.

By working

on myself and combining those insights with what I know of my learners, I can

begin to bridge our cultures in the classroom.

3. Bridge the Gap Between

Your Learners, Yourself, and Your Curriculum to Create Conditions for Learning

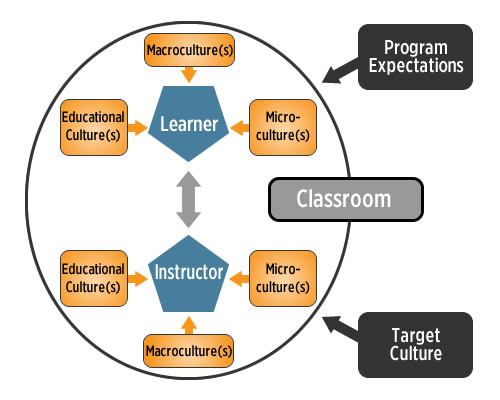

This tenet

is based on Gay’s (2018) component of establishing a supportive learning

environment and on Principle #2 of TESOL’s 6 Principles (2018), “Create

conditions for language learning.” Knowledge of my learners and myself alone is

insufficient for developing plans to meet my learners’ needs. My classroom does

not exist alone in space. It is influenced and shaped by both the educational

culture(s) in which I teach and the target culture(s) toward which I teach.

Figure 1 shows some of these complex interactions between my learners, myself,

and forces external to the classroom.

Figure 1. Interactions among factors affecting

classroom dynamics.

(Click here to enlarge)

Recognizing

the complex interplay of all of these factors and how they impact the classroom

dynamic is an ongoing effort that shapes my daily practice and helps me address

my learners’ needs in ways that are more responsive to my learners. One skill that

has greatly aided my ability to recognize these factors has been to listen

closely to my students. For me, listening extends beyond the obvious action of

hearing what students say and listening to what is left unsaid.

Listening

closely also means observing student interactions and behaviors and carefully

integrating what I have learned about my students into classroom activities in

such a way that gives students space to act in ways that are culturally

appropriate for them while potentially learning new cultural expectations. When

planning lessons, I ask myself if what I have planned respects students’

cultures and allows them to draw on their experiences to learn something new.

How to Implement an

ICCC

Implementing

an ICCC has been and continues to be a journey consisting of improving my

teaching and reflecting on myself, a process full of discovery. Unfortunately,

I have yet to find a manual or formula that tells me what to do when faced with

one set of circumstances or another.

That said, I

have, I have included a checklist (Appendix; .pdf) that can be used while

lesson planning. This checklist has been heavily influenced by the Mutually

Adaptive Learning Paradigm (DeCapua & Marshall, 2011). Using this

checklist can help facilitate a more culturally responsive classroom by raising

awareness of our own cultural expectations, thus facilitating cocreation of

knowledge in the classroom. I recommend using the checklist for each group of

learners you teach. Using it has helped me create more opportunities for

transformative learning to arise and has helped my teaching practice move

towards my goal of creating a true ICCC.

We

instructors may never become fully aware of our own privilege and cultural

biases, no matter how hard we try to uncover them. Nevertheless, the difficulty

of overcoming the hurdles these biases place on our teaching should not stop us

from working toward a more culturally responsive classroom—making this effort

every time we enter the classroom is one of the most powerful actions we can

take as allies in the fight for equity, and especially in these difficult

times. Achieving a true ICCC might well be impossible, but the practice of

working toward an ICCC results in subtle changes in the classroom over time.

With each change, the potential increases for the classroom to become a truly

transformative space for learners and instructors alike.

References

Byram, M.

(1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative

competence. Multilingual Matters.

DeCapua, A.,

& Marshall, H. W. (2011). Breaking new ground: Teaching

students with limited or interrupted formal education in secondary

schools. University of Michigan Press.

Gay, G.

(2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and

practice (4th ed.). Teachers College Press.

TESOL

International Association. (2018). The 6 principles for exemplary

teaching of English learners. TESOL Press.

Heather

Smyser has been teaching ESL to learners

ranging from newly resettled refugees to university-level students for the past

10 years. She received her PhD in second language acquisition and teaching from

the University of Arizona in 2016 and currently works as the program manager

for professional development at the Defense Language Institute English Language

Center. Her research concentrates on the emergence of print literacy and

fostering an interculturally competent classroom. |