|

My colleagues and I laughed the other day when someone asked

when course design is truly “done.” We all jokingly agreed “never,” and that is

in part true—as teachers, we are restless (sometimes obsessively so) in making

our courses the best they can be. The aim of this article is not to determine

when course design is finally complete, but rather to focus on evaluating

coherence in the design of a content-based course in an effort to maximize

student learning outcomes.

My colleagues and I laughed the other day when someone asked

when course design is truly “done.” We all jokingly agreed “never,” and that is

in part true—as teachers, we are restless (sometimes obsessively so) in making

our courses the best they can be. The aim of this article is not to determine

when course design is finally complete, but rather to focus on evaluating

coherence in the design of a content-based course in an effort to maximize

student learning outcomes.

I teach at

an art university that combines content from students’ majors (ranging anywhere

from fashion to fine art to architecture) into our English as a second language

classes. This integration of “language teaching aims with content instruction”

(Snow, 2014) is known broadly as content-based instruction. Our commitment to

content-based instruction is evident in the naming of our English as a second

language classes as “English for Art Purposes” (EAP). Students take their EAP

classes concurrent with courses that count toward their degree.

To make the

language learning authentic to our students’ majors, we rely significantly on

creating our own curriculum over adopting published textbooks. The particular

class that I teach is a high intermediate four-skill course in speaking,

listening, writing, and reading. When I first began teaching the course, there

was an established curriculum that was broadly related to art and design, but I

was tasked with redesigning the course specific to architecture, interior

architecture, and landscape architecture majors while still staying true to the

learning outcomes of the course. The first couple of semesters were admittedly

rough trying to adapt on the fly, but I was relieved to come across Stoller and

Grabe’s (1997, 2017) Six Ts approach to course design with themes,

topics, threads, transitions, texts, and tasks

to help evaluate what I was doing and to meaningfully connect the dots between

content and language in the course.

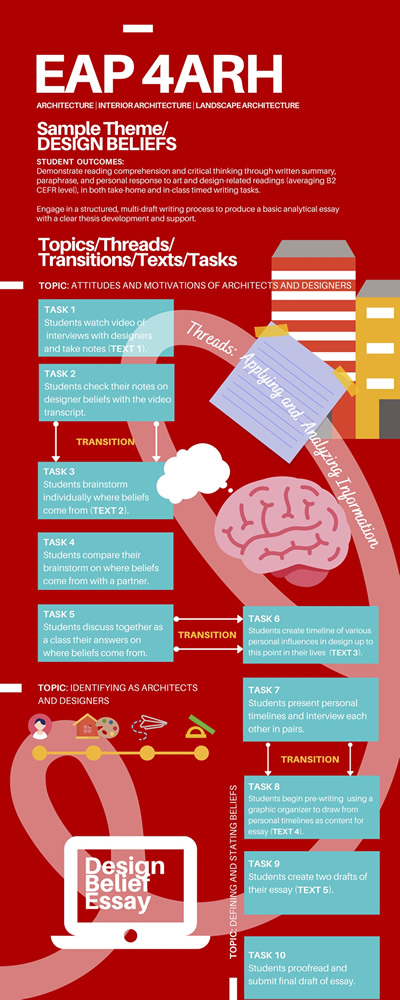

Stoller and

Grabe (1997, 2017) designed the Six Ts to be user friendly and widely

applicable to different contexts. I will briefly summarize each of the Six Ts

and describe their application to the course I designed. See the Appendix as a

visual example of how the Six T’s fit together in the course. Stoller and

Grabe (1997, 2017) designed the Six Ts to be user friendly and widely

applicable to different contexts. I will briefly summarize each of the Six Ts

and describe their application to the course I designed. See the Appendix as a

visual example of how the Six T’s fit together in the course.

1. Themes

Themes are

the overarching framework for the content that the course will organize itself

around. They can be abstract or concrete, and the focus and number of themes

will vary within each course. In evaluating the existing course, I realized

that if I were going to bring in content specific to the students’ majors, I

needed to have greater coherence between themes in order to deepen connections

with the content and language. Following are existing themes that were attached

to the course and the new themes that were adjusted to fit the now

content-specific course:

|

Existing Themes |

Revised Themes |

|

Beliefs about art

Opinions about art and art education

Reflecting on the learning process

Museums: Places for inspiration |

Learning to learn

Design beliefs

Design process |

2.

Topics

Topics

further break down themes by specifying aspects of the theme to be explored in

the course. A given theme can take different directions, and the topics of the

course can really address that relevant content that the students need. In my

case, as I tweaked the themes of the course on a broader scale, it was defining

the topics that allowed the course to get more major specific.

|

Themes and Topics |

- Learning to learn

- Characteristics of strong language learners

- Making a language learning plan

- Design beliefs

- Attitudes and motivations of architects and designers

- Identifying yourself as an architect and designer

- Defining and stating beliefs

- Design process

- Getting to know architects and designers

- Architectural concepts

- Precedents in architecture and design

- Design observation + analysis

|

3.

Texts

Texts are

the materials that provide the content to support the themes and topics of the

course. In a course without an assigned textbook, this is where much time

designing the course can be spent, as some of these materials must be compiled

(often adapted) and/or generated by the instructor (though certainly, a

published textbook could serve as a text in the course). Following are some

examples of texts in the course (not included are student-generated texts that

are the products of the tasks in the course, e.g., brainstorming,

pair work).

|

Texts |

Examples |

|

Instructor-compiled texts |

YouTube videos

Architecture Daily articles

Excerpts from “Thinking Architecture,” Dwell.com, Google Arts and Culture, and additional architect websites |

|

Instructor-generated texts |

Course reader

Grammar handouts

Quizlet vocabulary sets

Google Slides |

4.

Tasks

Tasks

include the instruction sequenced according to the themes and topics of the

course. They are the tangible, concrete activities that are supported by the

texts of the course and can encompass language, content, and strategy. In

essence, they are the means with which to fulfill student learning outcomes and

course objectives.

As such,

tasks can be grouped in a variety of ways according to the needs of the course.

For example, given that I teach an integrated skills course (reading, writing,

listening, speaking), each of the themes and topics is supported by tasks in

each of these skill areas. Tasks can be low-stakes (e.g., prewriting

activities) or high-stakes cumulative assessments (e.g., midterm/final exams,

project work) that come at the end of a topic or theme.

The number

of tasks and type of task is determined by the scope of the course. The

sequence of the tasks follows the progression and scaffolding of the theme and

topic, typically moving students from schema building to production and finally

to larger cumulative tasks. Here is a sample of tasks related to the theme of

design beliefs and under the topic of attitudes and motivations of architects

and designers:

|

Theme and Topics |

Tasks |

|

Theme: Design Belief

Topics: Attitudes and Motivations of Architects and Designers |

Listening to video, note-taking exercise, peer interviews, class discussion, mapping personal timeline, prewriting activities with graphic organizers, essay writing, vocabulary and grammar quizzes |

5. Transitions

Transitions

(along with threads, described in the following section) are like the glue that

bind the themes and topics together. Transitions are distinct from threads in

that they enable the teacher to help students provide connections between

topics, texts, and tasks. For example, in my course, students move from hearing

architects and designers describe their professions into exploring what

experiences and inspirations have influenced them. To transition, I might say

something like, “Now that you understand what it takes to be an architect and

designer, let’s talk about what attitudes and motivations shape an architect

and designer.”

|

Theme |

Topics |

Transition |

|

Design Beliefs |

Identifying yourself as an architect and designer

Attitudes and motivations of architects and designers

Defining and stating beliefs |

“Now that you understand what it takes to be an architect and designer, let’s talk about what attitudes and motivations shape an architect and designer.”

“We learned that beliefs support how an architect designs. Now, let’s explore what you believe about architecture and design.” |

6.

Threads

Threads

happen on the larger scale between themes in the course and tend to be more

abstract. If, for example, a course has the thread of visual communication,

possible themes that can be grouped under this thread are line, color, and

form. Threads bring greater coherence to the overall course. If teaching a

course with fixed content or a textbook, developing threads can help make

logical sense of how diverse themes come together. Threads do not always need

to be planned before the course begins, but can be discovered along the way.

Personally,

I think threads, if not already explicit, typically emerge having taught a

course more than once. In my course, it was after doing a needs analysis with

the architecture department that I determined students needed to develop their

critical thinking skills as designers. Thus, as I reworked the course and

integrated Bloom’s Taxonomy (Bloom, 1956) as a thread to help link the themes

together and help students become aware of moving from gathering information to

applying it, and then to finally analyzing it. This thread using Bloom’s

Taxonomy became even more clear after the course took on an additional

metacognitive objective to help students “learn how to learn” and be aware of

how they are thinking in order to become more independent language learners.

|

Themes |

Threads |

|

Learning to learn, design beliefs, design process |

Applying information (e.g., after identifying strong characteristics of language learners, applying these traits to being an architect and designer)

Analyzing information (e.g., after acknowledging design beliefs analyzing their role in the design process) |

Conclusion

The Six Ts

can be implemented at any point of course design—upon initial creation or as I

did in evaluating a course to bring in content and/or to add coherence. Even if

there is a textbook mandated by the institution, the Six Ts framework can help

fill in the gaps that the scope and sequence may be lacking.

Truthfully,

having the freedom to both select and create themes, topics, threads,

transitions, texts, and tasks in a course is quite time consuming, and as my

colleagues and I noted, there is something that always needs to be improved

upon. However, I find that evaluating a course using the Six Ts framework is

satisfying as a teacher, and, more important, I find that the students are the

ones who benefit most from the resulting cohesiveness in the course, with the

opportunity to make rich connections between the language presented and their

chosen majors. Additionally, with a multiskills course, the various language

skills of reading, writing, listening, and speaking have a more seamless

integration when the content is thoughtfully woven in.

I’ll end

with a short story—I was sitting with a former student in his architecture

studio the semester after he took my class. As the instructor lectured, a slide

flashed on the screen of one of the architects that we had discussed in our EAP

class. We both shot a glance at each other knowingly and smiled: Yes,

this subject has resurfaced in your major class—and you are now equipped with

the language to digest it even further!

References

Bloom, B. S.

(1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives, Handbook I: The cognitive

domain. McKay.

Snow, M. A.

(2014). Content-based and immersion models of second/foreign language teaching.

In M. Celce-Murcia, D. M. Brinton, & M. A. Snow (Eds.),Teaching English as a second or foreign language (4th

ed.). National Geographic Learning/Heinle Cengage Learning.

Stoller, F.,

& Grabe, W. (1997). A six-T’s approach to content-based instruction. In

M. A. Snow & D. M. Brinton (Eds.), The content-based

classroom: Perspectives on integrating language and content (pp.78–94). Longman.

Stoller, F.,

& Grabe, W. (2017). A six-T’s approach to content-based instruction. In

M. A. Snow & D. M. Brinton (Eds.), The content-based

classroom: New perspectives on integrating language and content.

(2nd ed., pp. 78–94). University of Michigan Press.

Sherise

Lee is the associate director of the

English for Art Purposes Department at the Academy of Art University. She

graduated from the University of California at Davis with degrees in art

history and sociology and went on to complete her MA TESOL at Biola University.

Her interests in the field include teacher education, content-based teaching,

curriculum development, program administration, and technology in education. In

addition to her work at the university level, Sherise has taught English to

elementary school students in China. |