|

College and career readiness initiatives within the United

States aim to prepare K–12 learners for increasingly complex life, learning,

and work environments. Across the school day, young scholars are expected to

experience lessons integrating meaningful task-based interactions. The anchor

speaking and listening Common Core State Standard for upper elementary and

secondary coursework details expectations for productive lesson discussion and

collaboration: SL1 “Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions

(one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with diverse partners on grade (3-12)

topics and texts, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly”

(CCSS, 2010). The standards architects clearly envisioned young scholars

dynamically interacting with peers, thoughtfully voicing their perspectives on

lesson content, and authentically listening. Though interdisciplinary educators

readily assign problem-solving and complex literacy tasks to peer working

groups, all too often they have failed to equip multilingual learners with the

requisite expressive and interpretive skills. A consistent area of

instructional benign neglect is explicit preparation in both the verbal and

nonverbal expectations for attentive listening during content-based lesson

interactions (Kinsella, 2016).

Students

approaching core content in a language they are striving to master embark upon

standards-aligned lesson interactions with pronounced listening challenges.

Rubin (1995) points out that listening during lesson exchanges poses inordinate

processing demands on second language learners because they “must store

information in short-term memory at the same time as they are working to

understand the information” (p. 8). In other words, the challenge of

interpreting a teacher’s discussion prompt and expectations for a partner

interaction or the assigned classmate’s perspective lies in the necessity to

process input immediately and accurately, unlike in reading, where there is an

opportunity to reread and digest the message. Students

approaching core content in a language they are striving to master embark upon

standards-aligned lesson interactions with pronounced listening challenges.

Rubin (1995) points out that listening during lesson exchanges poses inordinate

processing demands on second language learners because they “must store

information in short-term memory at the same time as they are working to

understand the information” (p. 8). In other words, the challenge of

interpreting a teacher’s discussion prompt and expectations for a partner

interaction or the assigned classmate’s perspective lies in the necessity to

process input immediately and accurately, unlike in reading, where there is an

opportunity to reread and digest the message.

Attentive Listening Training:

When Is It Needed?

Effective

communication during a collaborative process requires more than a relevant

lesson prompt, an affable elbow partner, and a conducive seating arrangement.

As an instructional coach, I have observed multiple red flags during lesson

observations that signal the need for a strategic intervention.

Predictable

indicators that a class has not received practical training for the attentive

listening demands of academic interaction include students who are displaying

one or more of the following behaviors:

-

not maintaining eye contact or

nodding to demonstrate active engagement;

-

speaking quickly and

softly, prohibiting their partner’s accurate auditory processing;

-

failing to ask clarifying

questions when they have missed a portion of a partner’s response or don’t

understand;

-

offering ideas that have

already been contributed without recognition; and

-

not providing affirming

feedback when lesson partners suggest an approach or provide relevant content.

Introducing Physical Features

of Attentive Listening

To

effectively implement interactive lesson tasks with multilingual learners, it’s

important to provide initial instruction in the physical features of attentive

listening in U.S. classroom settings. Norms and expectations for body language

during face-to-face exchanges can differ subtly or strikingly across cultures

and communities. Within workplace and academic settings in the United States,

for example, there are fairly consistent expectations that individuals

establish and maintain eye contact while conversing, whether with peers or

superiors, to demonstrate engaged listening and a modicum of respect. However,

development of this critical “soft skill” is often overlooked in teacher

preparation to work with students from diverse cultural and linguistic

backgrounds. We shouldn’t rely upon our students’ ability to function as

armchair anthropologists, skillfully noting communication protocol distinctions

between their prior schooling and current setting.

In my

experiences supporting multilingual learner communicative competence in K–12

and higher education, eye contact has proven to be the most nuanced and

sensitive component of nonverbal communication. I advise preparing thoughtful

notes to draw from when introducing this variable rather than improvising and

running the risk of further confusing students about protocols for face-to-face

interactions. I offer the following commentary for my students as a starting

point for discussion.

Sample Notes for

Introducing the Importance

of Eye Contact

In

the United States, looking at someone’s eyes as you speak shows respect and

active listening. It is so important in North American society that there is an

expression “to make eye contact,” just like two magnets making contact and not

coming apart. Looking away may tell the speaker that you are not interested,

distracted, nervous, or unprepared.

This isn’t universal. In

some communities and cultures, eye contact may not be so necessary or have

different rules for showing respect, such as a child not looking directly at an

elder’s eyes while speaking. Adjust your behavior and respectfully follow what

you know to be appropriate at home and in your community. But at school and

work, it is an expectation that you look directly at a person’s eyes when they

are communicating important information to you. It is also vital when you speak

to people who are helping you in official places, like a doctor’s office, a

bank, or a police station.

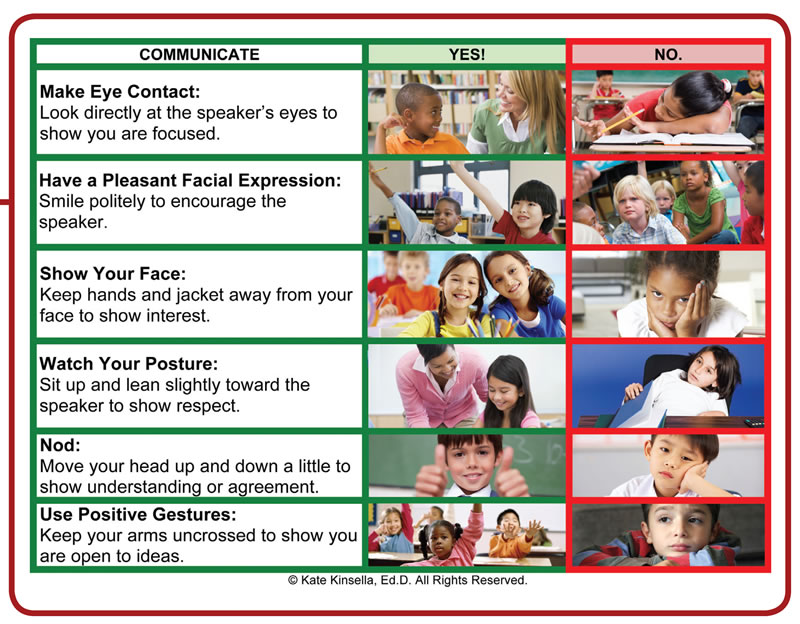

Preparing Visual

References for Nonverbal Features

Taking into

consideration the class’s age range and context for schooling, it is useful to

prepare a visual reference to graphically illustrate physical attributes of

attentive listening. For example, the poster shown in Figure 1 was designed for

elementary learners in a dual language program as part of a professional

development initiative to increase the quality and quantity of academic

interactions taking place across the school day. Students become more mindful

of their body language during class discussions, whether teacher-led or with

peers, when complemented by

-

nonjudgmental explanation,

-

modeling,

-

orchestrated practice, and

-

respectful reminders.

Conscientious attention to how they

are presenting themselves physically during interactions serves English

learners well as they navigate the school day communicating with different

teachers, instructional aids, classmates, counselors, and

administrators.

Figure 1. Demonstrating attentive listening:

nonverbal communication. (Click here to enlarge.)

Building Productive Verbal

Skills for Attentive Listening: Discussion and Collaboration

Classroom

academic interactions include two major task types: discussion and collaboration. Many educators use the terms conversation, discussion, and collaboration interchangeably. If an English learner

transitions from foundational coursework in a newcomer support context having

only been instructed to “think-pair-share,” it can come as quite a surprise

when core content-area teachers incorporate rigorous lesson tasks with

expectations for mature discussion or collaboration.

Types of Academic

Interactions

-

Discussion: exchanging ideas on an assigned topic with a lesson partner, group, or class,

drawing from text evidence, lesson content, background knowledge, or prior

experience

-

Collaboration: working together with a lesson partner or group on an assigned task to create a

mutually agreed upon and jointly constructed response, solution, or project

Both

academic interaction types necessitate more accountable listening than casual

sharing. To lighten the cognitive load for English learners, educators across

subject areas should strive for lexical precision when assigning lesson

interactions and specify whether it is a brief informal conversation using

everyday English, an academic discussion, or a collaborative endeavor. In this

way, novice English speakers will at least approach the task with a clearer

idea of the interaction process and intended outcome.

Addressing Language Functions

for

Discussion and Collaboration

To engage

appropriately in a lesson interaction and demonstrate attentive listening, all

students benefit from planned, intentional instruction in expressions to

accomplish a range of communicative purposes or functions (Dutro &

Kinsella, 2010). Academic discussion and collaboration involve several

overlapping language functions, but collaboration requires an additional

linguistic skill set. Both entail expressive uses of language, such as stating

and supporting opinions with evidence drawn from text sources, background

information, or experience. Productive discussion and collaboration focused on

academic content similarly hinge on recognizing others’ responses by agreeing,

comparing, or building upon what has been stated.

Additionally, within a mature

discussion or task-based collaboration, effective partners seek clarification

when a contribution isn’t entirely clear and restate to ensure they have a firm

grasp on intended meaning. Successful collaboration begins with equitable

discussion, gleaned either through a roundtable exchange or elicitation of

ideas by a proactive team member. However, the stakes for comprehension are

much higher with a collective response than with a simple exchange of ideas.

True collaboration on an assignment requires additional language skills for

providing feedback, making suggestions, and negotiating before jointly

completing the task and reporting on behalf of the team.

Sample Language

Functions and Expressions

for Discussion and

Collaboration

|

Compare Ideas

- My idea is a lot like (Name’s).

- My (opinion, reaction) echoes (Name’s).

- My response is similar to (Name’s).

- My (response, experience) is comparable.

- (Name) and I have similar understandings.

|

Agree With Ideas

- I agree with (Name) that ________.

- I completely agree with (Name’s) idea.

- I share your perspective.

- I see your point.

- A point

well taken.

|

|

Restate Ideas

- So, you think that ________.

- So, your (idea, opinion, example) is that ________.

- So, you’re suggesting that ________.

- Yes, that’s (right, correct).

- No, not

exactly. What I (said, meant) was

________.

|

Build Upon Ideas

- My idea

builds upon (Name’s).

- I appreciate (Name’s) perspective, and I would add that ________.

- That is a point well taken; however, I would point out that ________.

|

Sample Language Functions and

Expressions

for Collaboration

|

Contribute Ideas

- We could

(say, put, write) ________.

- What should we (say, put, write)________?

- I think ________ makes the most sense.

- I think ________ would work well.

- I think we should (add, include, consider) ________.

|

Affirm Ideas

- That makes sense.

- I see what you are saying.

- That’s a great (idea, suggestion, solution).

- That would work.

- I completely understand.

|

|

Clarify Ideas

- I don’t quite understand your idea.

- I’m not certain I understand your position.

- I have a question about ________.

- What exactly do you mean by ________?

- Can you explain what you mean by ________?

|

Report a Partner/Team’s

Ideas

- My partner

(Name) pointed out that ________.

- My partner (Name) indicated that ________.

- According to (Name), ________.

- We (decided, concluded, determined) that ________.

- Our (response, reason, opinion) is that ________.

|

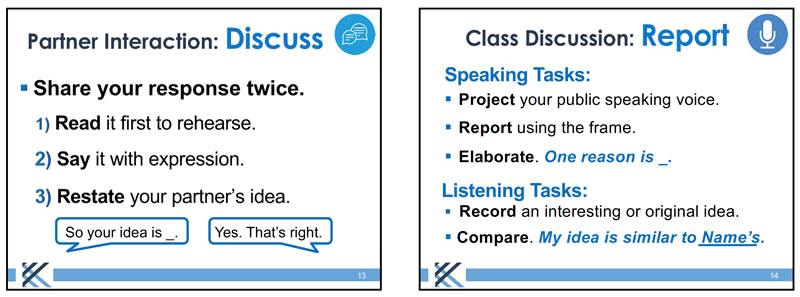

Preparing Directions for Lesson Interactions With

Attentive Listening Tasks

We can

support English learners in understanding the speaking and listening

expectations for planned lesson interactions by preparing clear visual

displays. In research and lesson coaching experiences, I have observed English

learners approach partner and group interactions unclear about the procedural

and linguistic expectations and needlessly struggling.

Rather than

entrust the roles, steps, and anticipated responses to their auditory

processing, prepare a set of visuals for common discussion and collaboration

tasks. Embedding direction slides in presentations works well, as does

displaying direction cards with a document camera. As students develop their

repertoire of useful expressions for common attentive listening tasks, such as

comparing and restating to verify understanding, proceed to more complex

language priorities such as paraphrasing and building upon and affirming ideas.

The slides

shown in Figure 2 were developed for a schoolwide endeavor to maximize student

verbal engagement and initiate all students, English learners and English-only

alike, to cross-disciplinary expectations for academic discussions.

Figure 2. Sample direction slides for partner

discussion and class discussion. (Click here to enlarge.)

Establish Concrete Listening Tasks for Class Discussions

Beginning

with novice English speakers in elementary and secondary contexts, I have

experienced considerable success establishing dual goals for attentive

listening in class discussions: 1) the focused listening and possible brief

note-taking task; 2) the language function(s) and key expressions.

1. Focused

Listening

Prior to

launching a unified-class discussion, concretize students’ listening task in

terms of the specific content they should focus upon and strive to record.

Merely encouraging students to “listen carefully” is not likely to reap

promising results. In addition to establishing consistent norms and expressions

for attentive listening, such as comparing and building upon previously stated

ideas, specify the content you are anticipating, whether an effective strategy

for solving a problem or a serious impact on the environment.

2. Identifying Key

Content

Having

clarified and visibly displayed class discussion expectations, as in the slide

(Figure 2), I am well poised to facilitate a brief postdiscussion partner

interaction requiring peers to identify the key content that caught their

attention. Knowing the class discussion will be followed by a partner

interaction builds in greater accountability for engaged listening.

I follow the

brief partner exchange by calling on a few students to share with the unified

class what they found most compelling, using the assigned frame, for example, An effective strategy I heard was ________. This final reporting activity proves

to enhance student interest while creating another vehicle for affirming

students’ unique contributions and respectful listening.

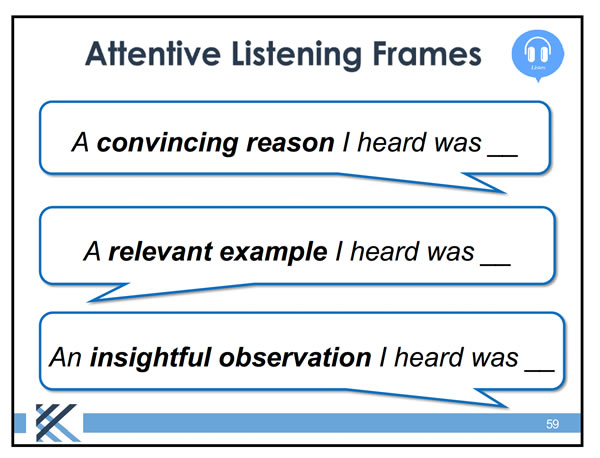

I recommend

preparing a suite of response frames such as those shown in Figure 3, each

incorporating a different type of listening goal for discussion prompts within

your curricula. Consider drawing from these common targets for tasks within

language and literacy instruction:

-

a

strong argument

-

a

well-justified position

-

a

thoughtful analysis

-

a

creative interpretation

-

a

relevant example

-

a

possible reason

-

a

major cause

-

a

serious effect

-

a

unique perspective

-

an

interesting experience

Figure 3. Attentive listening frames

examples. (Click here to enlarge.)

Final Thoughts

Instituting

school-wide teaching practices for academic discussion and collaboration with

established speaking and listening expectations will increase the odds that

multilingual learners are equitably prepared to handle with aplomb the demands

of real-life listening during vital interactions in their social, academic, and

professional lives.

Additional Lesson

Resources

References

Common Core

State Standards. (2010). Applications of Common Core State Standards for

English language arts and literacy. http://www.corestandards.org

Dutro, S.,

& Kinsella. K. (2010). English language development: Issues and

implementation in grades 6-12. In Improving education for English

learners; Research-based approaches (pp.151–207). California

Department of Education.

Kinsella, K.

(March, 2016). Attentive listening: An overlooked component of academic

interaction. Language Magazine, 28–35.

Rubin, J.

(1995). Introduction. In D. J. Mendelsohn & J. Rubin (Eds.), A guide for the teaching of second language listening (pp.

7–12). Dominie Press.

Kate

Kinsella, EdD writes curriculum, conducts

K–12 research, and provides professional development addressing evidence-based

practices to advance English language and literacy skills for multilingual

learners. She is the author of research-informed curricular anchors for K–12

English learners, including English 3D, Language Launch, READ 180 ReaL Book,

and the Academic Vocabulary Toolkit. |