|

We know that to succeed academically, multilingual learners

(MLLs) need to both understand and accurately use a rich, varied lexicon,

especially in writing. As Engber (1995) explains, the size and quality of

vocabulary is the strongest correlation to ratings of papers (based on a study

of texts written by intermediate second language writers).

Certainly, students can learn vocabulary passively

with flash cards and quizzes on definitions. However, this decontextualized

method is not enough to give students the confidence to produce these words.

But beyond flash cards, how can students master difficult words found on

academic vocabulary lists?

This article offers three focused activities to

help students better understand and use academic vocabulary: The Associations

Game, The Book of Records, and My Categories. Each offers a different way for

students to make a personal connection to the words while offering room for the

instructor to supervise and give feedback. I have chosen college-level words to

illustrate that these activities can be used with less frequent terms, but they

are flexible and will accommodate a wide range of word lists. All of these

activities can be adjusted for time by increasing or decreasing the size of the

word list or the number of examples required.

Activity

1: The Associations Game

The Associations Game is a review that helps

students engage with academic words through self- and peer-generated examples.

It is especially useful for more abstract terms and less frequently used words

that might not be encountered outside of the classroom.

Time: 40 minutes

Materials: Paper cut into

strips, scissors, and a different list of 10–15 words that students have

encountered before for each group. (Try to avoid words that are very similar in

meaning.)

Warm Up

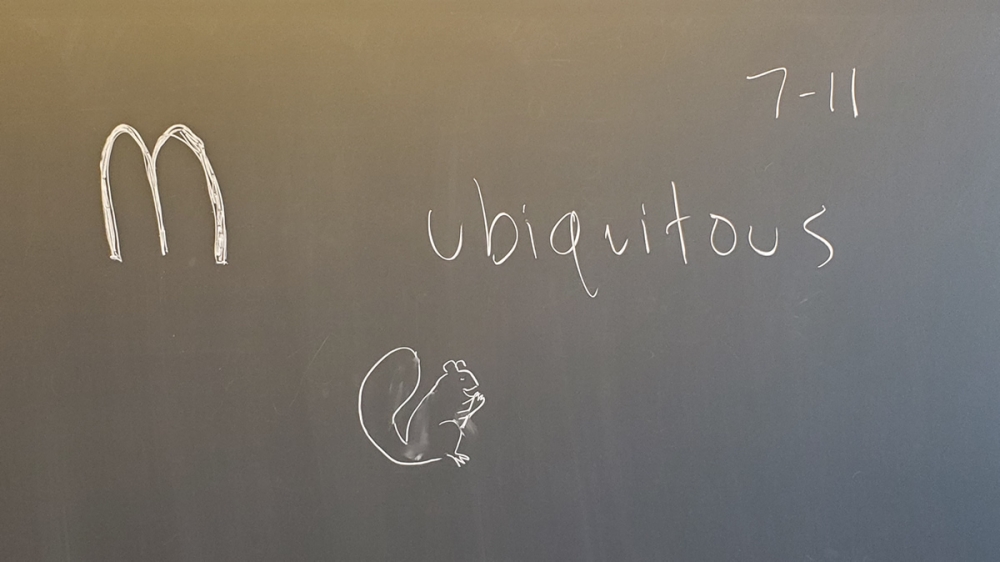

Before distributing the paper slips, write a

familiar word on the board. Ask students what the word makes them think of. The

example they give can be a person, place, thing, situation, experience, or

feeling and can be expressed as an example: a word, phrase, sentence, or

picture. To encourage students to make personal connections, stress that this

should be an example, not a synonym or definition.

For instance, the simple word hot may conjure up pictures of the sun or fire for some

students. Others may imagine a “hot” actor or fashion trend. The more academic

word ubiquitous could elicit the example of Starbucks,

event posters in the hallways, or the squirrels that are everywhere on campus.

Write or draw their examples next to the word.

Clarify vague or ambiguous suggestions.

Sample Wordlist

|

affluent |

embellish |

malicious |

amorphous |

expiration |

|

collaborate |

detriment |

oblivious |

reek |

fritter |

|

terse |

surreptitious |

ubiquitous |

perplex |

dwindle |

How to Play

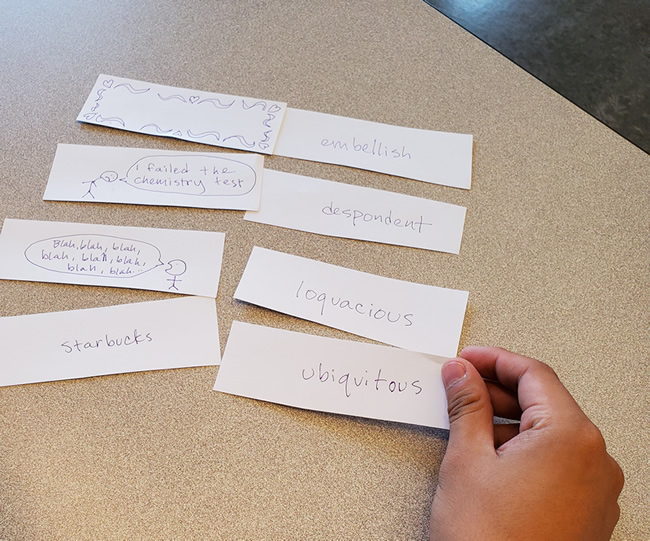

First, divide the students into an even number of

groups of with three to four students each and give each group a set of 10–15

blank strips of paper (one for each word). Students write the vocabulary words

on the left side of blank strips. They then put one example for each word on

the right side. Check student answers as they write them to ensure that their

examples are appropriate.

Click here to enlarge.

After the students have filled out as many strips

as they can within 20 minutes, they cut the completed ones in half with

scissors and mix up the papers. Any uncompleted strips are discarded. Each team

then exchanges their set with another group. The teams then try to re-create

the original combinations. After they have finished, someone from the team that

wrote the examples should check them.

Note: Set a timer for 20

minutes for the first part and call time for students to stop working, then

exchange the mixed-up sets of strips. Make it clear to students that they do

not need to finish all the words in the time allotted.

Activity

2: The Book of Records

The Book of Records is a game I initially devised

for students to practice comparative and superlative adjectives—and it is still

useful for that! However, whether students are still mastering that skill or

have gone beyond it, the Book of Records is a great way to practice using words

in a fun way.

The name of the game should be based on the name of

your school or program (e.g., “The Smith School Book of Records”). Because

students will vie to be a “winner” in their class, be sure to include

categories that a variety of students might win—whether that is a hobby or the

amount of homework they get every week.

Time: 30–40 minutes, depending

on the number and difficulty of questions

Materials: A list of questions

about superlative qualities that use vocabulary students know passively.

Warm Up

Start by writing a few superlative questions on the

board. For instance, “Who is the most versatile actor?” or “Which Olympic sport

is the most exciting?” As students suggest candidates, ask them to support

their answers with reasons.

How to Play

Break students up into groups of four or five. Each

group receives the same list of six to eight questions—each containing a

superlative. Students must give examples to support their claim to the record,

and records are determined by consensus. The type and number of questions will

determine the length of the exercise. For instance, “Who can tell the most

terrifying story?” will take a long time. “Who is the most dexterous?” will

take less time.

Once each group has determined its “record

holders,” those students will go on to compete for the class record in front of

the class. Final winners will be determined by the class.

Example Questions

- Who can say the English alphabet the most

rapidly?

- Who is the grouchiest when they wake up in the

morning?

- Whose favorite animal is the fluffiest?

- Who was the most sedentary this week?

- Who can tell the most hilarious joke?

- Whose day was the most hectic?

Activity

3: My Categories

Finally, My Categories is a great springboard to a

writing activity as well as a way to practice vocabulary. It is possible to

categorize words in many ways—groupings like “verbs,” “words from Latin,” or

“words to describe a person” can be useful—however, for this exercise, the idea

is for students to create categories that draw on their own experiences and

interests.

Time: 30 minutes

Materials: Blackboard and a

list of at least 25 words students know passively

Warm Up

After giving students the word list, write a

category of your own on the board. The category should be as specific as

possible and should be based on meanings. Begin to add

words and explain why each fits your category. Ask students for other words

from the list they think would fit your category and write these on the board

as well. Make sure that students understand there is no right answer.

Sample Wordlist

|

scanty |

sphere |

boast |

foible |

exhibit |

drizzle |

|

habitat |

clumsily |

isolated |

relaxed |

debate |

mammoth |

|

summon |

briskly |

drooping |

invisible |

adoringly |

bewildered |

|

author |

rage |

benefit |

shambles |

livelihood |

dominate |

|

mimic |

sweltering |

gruesome |

miniscule |

woe |

superficial |

Examples of Model Categories

“Words about my garden”

- Habitat—for insects

- Mammoth—the size of the sunflowers in

August

- Benefit—the flowers benefit butterflies

- Drooping—the flowers if they don’t have enough

water

“Words about my commute to school”

- Briskly—how I walk to the subway

station

- Woe—if I miss the train, I’ll be late to

work!

- Sweltering—the temperature on the subway in the

summer

How to Play

Students work in pairs to create three categories

of three to five words each from the list and write them on a paper or the

board. They should include their reasons for selecting each word. After they

finish, groups read their favorite examples to the class. As mentioned earlier,

this activity is a great lead-in to writing; students can expand on each list

to create a complete paragraph.

Conclusion

These are just a few of the ways you can give

students opportunities to practice academic vocabulary. As they move through

the semester, they build personal connections to items in their word lists,

helping them to thrive in their content classes.

Reference

Engber, C. A. (1995). The relationship of lexical

proficiency to the quality of ESL compositions. Journal of Second

Language Writing, 4(2), 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/1060-3743(95)90004-7

A. C. Kemp has been a lecturer in English language studies at MIT since 2007. She has a master’s degree in applied linguistics from the University of Massachusetts/Boston. A. C. has also presented extensively on teaching strategies for vocabulary acquisition. Since 2002, she has been the director of Slang City, a website devoted to American slang and colloquial language.

|