|

The Corpus of Global Web-Based English (GloWbE),

released in April 2013, is freely available here. With 1.9 billion words

from nearly 2 million web pages from 20 English-speaking countries, it

uses the familiar interface of other Mark Davies corpora such as the

Corpus of Contemporary American English. For those not acquainted with

the other corpora developed by Mark Davies, the site has brief

explanations of the major features and a 5-minute tour that illustrates

various types of searches.

The countries represented in GloWbE include inner, outer, and

expanding circle Englishes: the United States, Canada, Great Britain,

Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh,

Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, Hong Kong, South Africa, Nigeria,

Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania, and Jamaica. A helpful feature of the corpus is

the ability to exclude countries and groups of countries to make

comparisons. So it is possible to compare North American English—spoken

in the United States and Canada—with British English, to focus on

regions such as Southeast Asia, or to look at the English of the

different circles.1

To acquaint myself with GloWbE, I used it to investigate the

use of more clear, a phrase which I have been

hearing—and reading—frequently in the United States. I speculated that

perhaps the outer circle countries were influencing the traditional

formation of comparative adjectives in U.S. English.

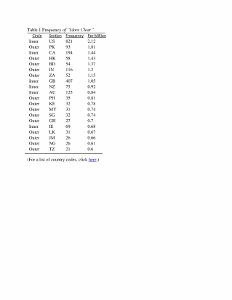

My speculation was not supported. As seen in Table 1, in GloWbE

both the absolute frequency and frequency per million words of more clear is greatest in the United States, but the

countries with the least frequent occurrences per million words tend to

be outer circle countries. Of the 10 countries at the bottom of the

frequency list, only Ireland is not an outer circle country.

Table 1 Frequency of More Clear (click to enlarge)

(For a list of country codes click here)

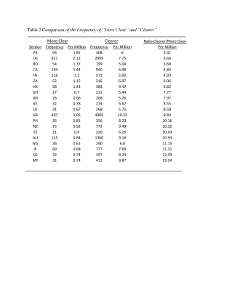

Searching GloWbE for more clear and then clearer gave the results shown in Table 2. As seen,

the traditional clearer is still more common in the

United States as it is in all of the countries represented in GloWbE.

Pakistan had the smallest frequency per million ratio, 3.31, meaning

that clearer occurred in GloWbE only a little more

than three times as frequently as did more clear.

Pakistan was followed by the United States with a frequency ratio of

3.66. However, clearer occurs over 10 times more

frequently than more clear in the Philippines, New

Zealand, Tanzania, Australia, Nigeria, Ireland, Singapore, and Malaysia.

Once again, it does not appear that the outer circle countries are

influencing the United States.

Table 2 Comparison of the Frequency of More Clear and Clearer (click to enlarge)

So what was learned from this exercise with GloWbE? The

traditional form of the comparative, clearer is still

more frequent than more clear in U.S. web pages—over

three times more frequent. Another way of saying this is that clearer is still more probable. And it is possible to

state that clearer is much more probable in many

other countries, with the ratio being over four times greater in

Malaysia than in the United States. Furthermore, contrary to my initial

speculation, there is no reason to believe that formation of the

comparative in U.S. English is being influenced by outer circle

countries’ English.

Jenkins (2006) noted several years ago that research into World

Englishes “has immense implications for TESOL practice in all three

circles and above all in terms of the kind of language we teach” (p.

171). TESOL (2008) has recognized in a position statement that,

as a result of complex economic, cultural, and technological

forces, such as the growth of international trade and the Internet, the

English language is now used worldwide, with a geographic spread unique

among all world languages. . . . As a result, the vast majority of those

using English worldwide are themselves nonnative speakers. This has had

a profound effect on both the ways English language teaching (ELT) is

practiced and the language itself.

GloWbE will be helpful to scholars and teachers interested in

the “diverse users and uses of English” in inner, outer, and expanding

circle countries (Bolton, Graddol, & Meierkord, 2011, p. 474).

For me, GloWbE provided data to disconfirm my speculation that was based

on intuition. I can now say with some confidence that although more clear is relatively frequent on U.S. websites, clearer still predominates, and that the use of more clear on U.S. websites does not appear to result

from outer circle influences.

Yet I have not explained the reason for the variation in

comparative forms apparent among the 20 different English-speaking

countries represented in GloWbE. As pointed out some years ago by

Celce-Murcia and Larsen-Freeman (1999),

the “rules” . . . for the comparative inflection are not as

rigid as those for the plural or past-tense inflections. We regularly

hear English speakers use a periphrastic form for emphasis . . . when

the “rule” would predict the inflection. There is also some individual

variation. (p. 721)

A follow-up to the quantitative analysis above would be a

qualitative examination of the GloWbE data to investigate

sociolinguistic variation in the use of more clear in

web pages.

Note

1 Inner Circle countries are the traditional English-speaking

countries; Outer Circle countries are those where English is used as an

institutionalized, official language, though it may be an additional

language for many; and the Expanding Circle countries are those where

English does not have an official status, but is used in commerce and is

studied as a foreign language. See Table 1 for a

classification.

References

Bolton, K., Graddol, D., & Meierkord, C. (2011).

Towards developmental world Englishes. World Englishes, 30, 459–480.

Celce-Murcia, M., & Larsen-Freeman, D. (1999). The grammar book: An ESL/EFL teacher’s course (2nd

ed.). Boston, MA: Thomson Heinle.

Jenkins, J. (2006). Current perspectives on teaching world

Englishes and English as a lingua franca. TESOL

Quarterly, 40, 157–181.

TESOL. (2008). Position statement on English as a

global language. Retrieved from http://www.tesol.org/docs/pdf/10884.

Roger W. Gee is a Professor at Holy Family University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA where he is the Director of the Masters in TESOL and Literacy Program. His interests are second language literacy, language and literacy assessment, and the use of corpora in teacher education. |