|

Jose Franco

|

|

Kara Mac Donald

| Vocabulary teaching becomes deficient when it is focused purely on word meaning in the mother tongue; such a focus is also associated with learners’ language inaccuracy, lack of reading comprehension, and lexical transfer. This article focuses on collocations as an effective way to apply the lexical approach (Lewis, 1993), which aims to enhance and expand vocabulary teaching considering not only words in isolation, but also their partnerships—a prerequisite for word knowledge (Farghal & Obiedat, 1995). The current contribution also shows how the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) can be employed as a primary resource in lexical instruction through the implementation of feasible classroom activities (Dash, 2015).

Corpus of Contemporary American English

The COCA is a highly representative corpus that contains more than 560 million words. According to Yusu (2014), it is the largest free English corpus available, and it also has significant advantages over other free corpora in terms of vocabulary study (Davies, 2009). Users don’t need to be experts in informatics to get access to all the corpus features. The COCA contains five registers: 1) spoken, 2) fiction, 3) popular magazines, 4) newspapers, and 5) academic texts. What makes COCA a valuable resource in EFL classrooms is the way it shows users how language behaves by means of its concordance lines.

How to Implement COCA in Your Classes

Before starting to use COCA, we recommend two pivotal elements for teachers to consider: 1) student registration on COCA so that they can log in and access the corpus, and 2) a predesigned exercise sheet focused on the target collocations (Reppen, 2010).

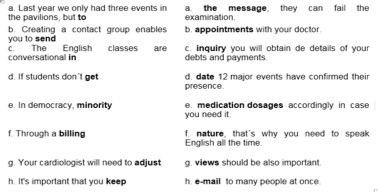

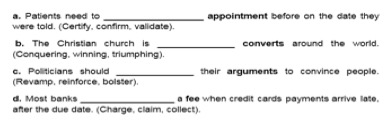

After you ask students to access the corpus using one of their accounts (they can work in pairs), give them a predesigned exercise sheet. The sheet should contain two sections: a matching activity and a gap-fill task. In the matching activity, ask students to match the elements in Column A with the elements in Column B to complete the bolded collocations in the sentences, as shown in Figure 1. To accomplish this activity, students employ the collocates search box of the corpus to find collocates for the node words. Because some node words in the sentences may collocate with more than one option in the opposite column, students need to consider also the context to match them properly.

Figure 1. A predesigned matching activity.

Students are asked to search for collocates before and after the node word or phrase, as shown in Figure 2. It is important to remind them how to employ the POS list (Parts of the Speech) in the Collocates box to refine their search.

Figure 2. Collocates search for the message.

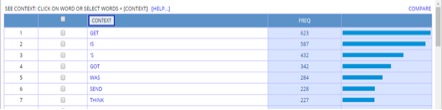

Results of the search are a good source of discussion. Thus, it is important that students share and discuss their search results, putting special emphasis on meaning, frequency, and its implications on the matching activity (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Collocates for the message.

In the gap-fill task, students need to choose one of the near-synonyms collocates to complete the sentence, as shown in Figure 4. Ask them to search for collocates (verbs) before the node words.

Figure 4. Gap-filling task with near synonyms.

As previously stated, search results are necessary for students to share and discuss. It is important also to analyze and share the choices they made to fill in the gaps. This way, they can understand that near-synonyms, because of their nature, are not freely interchangeable in collocations. At this point, it is pivotal to make students reflect on the importance of collocations in the English language.

Conclusion

COCA is a powerful tool to teach vocabulary/lexicon. However, despite the autonomy this tool can offer learners, they initially need to be guided by the teacher through the learning process, not only to help them employ the corpus features effectively but also to help them navigate the large number of entries a search can generate. Students can get overwhelmed or confused; consequently, the teacher needs to direct their attention to the most appropriate language samples, taking into account factors such as their proficiency level. Combining data-driven learning with output tasks can increase its effectiveness (Donesch-Jezo, 2011).

References

Dash, N. S. (2015). Corpus-based English language teaching: A new method. Journal of Advanced Linguistic Studies, 4(1-2), 151–171.

Davies, M. (2009). The 385+million word corpus of contemporary American English (1990-2008+): Design, architecture, and linguistic insights. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 14, 159–190.

Donesch-Jezo, E. (2011). The role of output & feedback in second language acquisition: A classroom-based study of grammar acquisition by adult English language learners. Eesti ja Soome-Ugri Keeleteaduse Ajakiri, 2(2-2). https://doi.org/10.12697/jeful.2011.2.2.01

Farghal, M., & Obiedat, H. (1995). Collocations: A neglected variable in EFL. IRAL, 33(4), 315–333.

Lewis, M. (1993). The lexical approach: the state of ELT and a way forward. Language Teaching.

Reppen, R. (2010). Using corpora in the language classroom. Cambridge University Press.

Yusu, X. (2014). On the application of Corpus of Contemporary American English in vocabulary instruction. International Education Studies, 7(8), 68–73.

Jose Franco is an assistant professor in the Department of Modern Languages at the University of The Andes in Trujillo State, Venezuela. He provides training to preservice EFL teachers and also teaches ICT and ESP to diverse types of professionals. He is coordinator of the English Language Unit at his university and has been an active member of Venezuela TESOL (VenTESOL), global member of TESOL International Association, and assistant manager/editor of the KoTESOL web page InterComm Chapter since 2018. He earned a MEd in TEFL and his research interests include CALL, corpus linguistics, lexicon, and interrupted education.

Kara Mac Donald is an associate professor at the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California, USA. She conducts preservice and in-service faculty training and offers academic support to students. She maintains a close connection to the English language classroom as a part-time ELL instructor for children and young adults in ESL, academic writing, and academic test preparation courses. She has been a member of KOTESOL since 2006 and active in a variety of roles and has been the editor-in-chief of the Korea TESOL Journal since 2014. Her background consists of more than 25 years in foreign language teaching, teacher training, curriculum design, and faculty development across elementary, secondary, and higher education in the United States and internationally. She earned a master’s in applied linguistics, TESOL, and a doctorate in applied linguistics.

|