|

“I feel proud of myself because I got to make all of the

things I wanted to tell everyone. Because people wants to know how I

lived in Burundi.”

–Aaliyah, arrived from Burundi in 2010

“I do it for the people. They need to see how I am in my country. You know, it’s not good in my country.”

–Ameer, arrived from Iraq in 2010

“I learned that the United States is made out of immigrants…I

never knew that, and it was just really interesting to me because it

just made me think about everybody.”

–Keegan, whose ancestor arrived from Poland in 1912

These are just a few of the heartfelt reflections from students

Grades 3–5 following the completion of their own family immigration

stories, which they carefully crafted in pictures and in words

(Olshansky, 2015). Newcomers reconstructed their family’s recent journey

from their native country to the United States; students whose families

immigrated long ago reconstructed the imagined journey of their first

ancestor to travel to America. Though students’ pride in their published

books was palpable, what also became apparent was the way this

bookmaking project transformed not only the culture of the classroom and

the school community, but also that of the greater community beyond the

school walls.

Abdullah displaying his work.

A Universal Language

The process used to create family immigration stories is known

as “image-making within the writing process.” This collage-based

approach to teaching writing and strengthening reading was originally

validated by the U.S. Department of Education as an innovative and

effective literacy program in 1993 (Olshansky, 2008). Because pictures

serve as a universal language, the image-making process has found a

natural home among English learners and their teachers. It has also been

used by classroom teachers who recognize the diversity of learners

within their own classroom community. Proven effective for a wide range

of learners (Frankel, 2011) and easily integrated into the social

studies and science curriculum, this enticing pictures-first approach to

writing has reached new heights of personal engagement when applied to

crafting family immigration stories.

Kara looking over her work.

A Unique Visual Approach to Literacy Learning

Unlike most approaches to teaching writing which focus on the

written word, image-making within the writing process is designed to

support students who, for one reason or another, have difficulty with

written or spoken language. Visual tools for thinking, developing, and

recording ideas are woven throughout the process.

Students began this immigration unit by watching a short video

entitled Our Stories in Pictures and Words as Told by Immigrant

and Refugee Children (Olshansky, 2010).

During this 13-minute film, students are invited into the classroom of

English learners in the process of creating their own family immigration

stories using collage from hand-painted papers. While viewers were

introduced to the process and the stunning books the English learners

created, they also learned about the circumstances that resulted in

families recently fleeing their country. This awareness helped set the

stage for students to create their own image-making immigration stories.

English learners saw that it was alright to share their stories and, in

fact, witnessed the pride fellow newcomers experienced after creating

their own books. As recent arrivals, they understood that it was an

important, and particularly meaningful, personal accomplishment. In the

video, Priyanka reflected, “In Nepal we didn’t do like that. We don’t

have color to do like that. And we didn’t have paper, and we didn’t glue

like that. I didn’t think in America I do like that, to make that book”

(Olshansky, 2010).

For students whose ancestors arrived long ago, watching the

film of children their own age sharing their stories was particularly

moving. Attending school in a rural New Hampshire community that lacks

diversity, students found the immigration stories of their peers

poignant and eye opening. Third grader Lizzy confessed, “I actually

didn’t know that there are people still immigrating and coming today.”

Leah acknowledged, “I learned that the Webster kids went through things

that I could never imagine.” Liam added, “If I were an immigrant and

immigrating to a different country it would be really tough” (Olshansky,

2015). This was the first of many discussions in which students with

well-established roots in this country displayed empathy and compassion

for those students who had recently immigrated.

During this partnership between students from two very

disparate communities, English learners discovered that almost everyone

in the United States originally came from somewhere else. This helped to

establish some common ground with others in their community. As for

those students whose ancestors arrived long ago, most had never before

considered where their families originated. This triggered a natural

curiosity about their family stories. Alec explained, “Well I knew that

the Pilgrims came for religious reasons, so I was wondering about my

family, where did they come from and why” (Olshansky, 2015).

Quality Picture Books as Mentor Texts

Because the image-making process is designed to meet the needs

of a wide range of learners, it relies heavily on use of the visual and

tactile modalities. Teachers use quality picture books as mentor texts.

These books, often historical fiction, depict their content in both

pictures and words. This is particularly helpful for English learners,

though the illustrations in these books are used as visual resources by

all students when it comes time to depict various aspects of their own

or their ancestors’ journey.

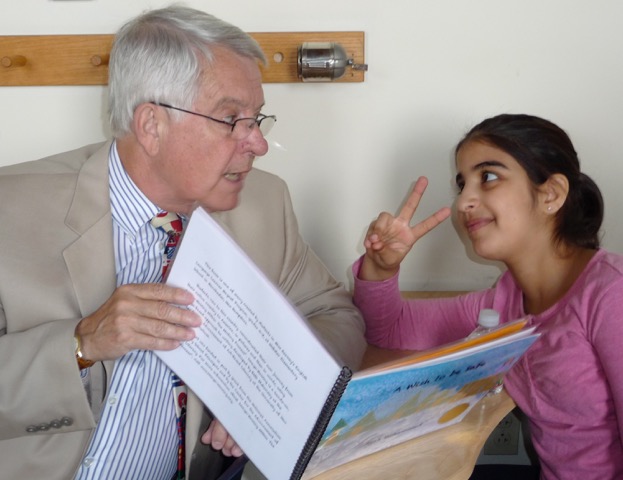

Dennis and Ayat in discussion.

Constructing Story Shape by Shape

During this 2-month project, students undertook in earnest the

process of reconstructing their own or their ancestral family

immigration story. Unique to image-making within the writing process,

students began by creating their own portfolios of hand-painted textured

papers. Using a variety of simple art techniques, students experimented

with color and texture in a systematic yet open-ended way. For our

newcomers, some of whom had never had access to paints before, the

process was particularly compelling.

Following explicit modeling of the process of crafting an

immigration story page by page, students began cutting into their

hand-painted papers and laying shapes onto a background paper. With the

aid of thoughtfully designed storyboards, students created a sequence of

collage images that captured key moments along the journey. Because of

the universality of pictures, this pictures-first approach allows

students to secure their ideas on paper before having to tackle creating

the written text. This makes story drafting particularly accessible to

English learners.

Anna reviewing her work.

Reading the Pictures

Once students’ ideas are glued to the page, they are invited to

read their collage images to access details and description. As

students point to each collage and read that picture, the oral rehearsal

process helps students to “practice their story.” It also helps English

learners identify and learn the words they will need to tell, and

ultimately write, their stories.

The Power of Perspective

Both sets of stories, those created by English learners as well

as those created by native English speakers, are written in the first

person. Though this is an obvious choice for those who actually

experienced the journey, writing from the first-person forces students

who are writing ancestral stories to imagine and relive the journey of

their ancestor as if it were their own. This helps to deepen their

understanding of the immigrant experience.

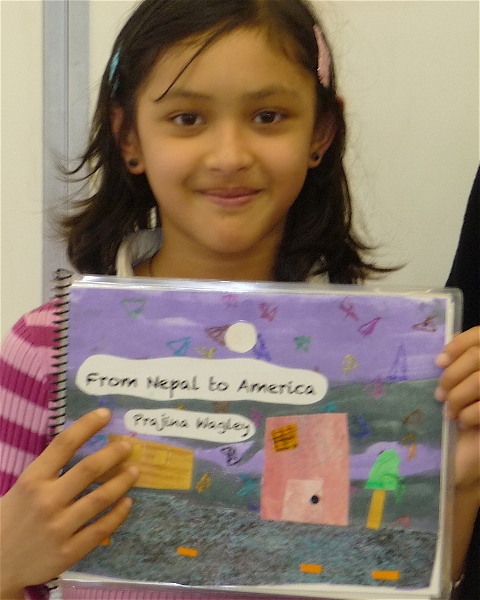

Prajina showing her work.

Finding Common Ground

The experience of creating their own carefully crafted family

story was personally meaningful for all students, and opportunities to

share these family immigration stories resulted in positive impacts far

beyond what was originally imagined. Newcomers and U.S.-born students

discovered that their family stories had many similarities. Alec

observed, “I noticed that today’s immigrants and immigrants from the

past faced the same challenges.” He noted that many came for “pretty

much the same reasons…for religious freedom, need more food, bad choices

were being made in the country…” (Olshansky, 2015).

As our native English speakers tried to imagine the experiences

of their first ancestors to come to America, they developed deep

empathy and respect for those students who had recently arrived in this

country. Zoey shared, “I think that the people who came across were

really brave and stuff. I couldn’t really imagine doing that myself”

(Jones, 2011).

When the students’ books were placed on display, other

students, teachers, administrators, parents, and members of the greater

community developed greater awareness and respect for what our newcomers

have gone through. While the parents of English learners were visibly

proud of the accomplishments of their sons and daughters, other parents

and adults within the community were humbled by what they learned about

the challenges today’s immigrant families face. They were also reminded

that their ancestors experienced similar struggles and once benefited

from the opportunities afforded them at the time of their

arrival.

Zoey working hard at writing.

Lessons Learned

At this time in history when immigration has been an explosive

political issue and some politicians seem to have forgotten that they

are here today because their ancestors were once welcomed into this

country, this classroom immigration project served not only to develop

greater awareness but also to build compassion and empathy within the

community. Eight-year-old Alec, wise beyond his years, reminds us, “I

learned that if our ancestors didn’t come over here at the exact period

of time that they did, pretty much all of our lives would have been

different.” Leah realizes that if her grandfather hadn’t arrived exactly

when he did, “he wouldn’t have married who he did so I wouldn’t have

been born” (Olshansky, 2015). For English learners and U.S.-born

students alike, this deep dive into the study of immigration, in the

most personal way, provided students with a deeper understanding of the

role their families play in shaping history.

References

Frankel, S. (2011). Picturing writing: Fostering

literacy through art. Retrieved from

http://www.picturingwriting.org/pdf/AEMDDFindings.pdf

Jones, C. J. (Producer). (2011). Immigration stories

through pictures & words [video segment]. United

States: New Hampshire Chronicle. Retrieved from

http://www.picturingwriting.org/NH_Chronicle.html

Olshansky, B. (2008). The power of pictures: Creating pathways

to literacy through art (pp.188- 190). San Francisco, CA:

Jossey-Bass.

Olshansky, B. (Producer). (2010). Our stories in

pictures and words as told by immigrant and refugee children [DVD]. United States: Center for the

Advancement of Art-Based Literacy, University of New

Hampshire.

Olshansky, B. (2015). Coming to America: Telling our

stories in pictures and words. United States: Center for the

Advancement of Art-Based Literacy, University of New

Hampshire.

Beth Olshansky is director of the Center for the

Advancement of Art-Based Literacy at the University of New Hampshire in

Durham, New Hampshire, USA. You can find links to several video clips

and additional information at her website, Picturing Writing:

Fostering Literacy Through

Art. |