|

Written feedback plays an important role in second language

writing. It encourages learners to focus on form, providing them with

opportunities to notice the gap between their interlanguage and the

target language form (Schmidt, 1990; Schmidt & Frota, 1986). As a

second language writer, I believe that written feedback has great

value. Especially when a native speaker gives me feedback, I am assured

that my writing quality and accuracy will be much improved. During my

graduate studies, I have received written feedback from teachers and

writing tutors in terms of writing content, mechanics, grammatical

aspects, and word choice. In these various experiences, I have observed

that different people have different approaches to giving feedback. Some

teachers prefer to give direct feedback and correct my inaccurate

expressions, while some instructors like only to highlight mistakes, but

later add comments for me to self-correct the mistakes. Among the

feedback approaches I have experienced, I am very impressed by reformulation for its feedback strategy in the form

of rewriting my original text.

Reformulation has received considerable attention in recent

years (Lapkin, Swain, & Smith, 2002; Sachs & Polio,

2007; Thornbury, 1997). As defined by Ellis (2009), reformulation

“consists of a native speaker’s reworking of the students’ entire text

[including but going beyond sentence-level concerns] to make the

language seem as native-like as possible while keeping the content of

the original intact” (p. 98). Sachs and Polio (2007) compare the

efficacy of direct error correction and reformulation on the linguistic

accuracy of ESL students’ writing. They provide an example, illustrating

both feedback approaches below, and assert that the key differences

between the two are “a matter of presentation and task demands and [are]

not related to the kinds of errors that were corrected” (p.

78).

(1) Original version: As he was jogging, his tammy was shaked.

(2) Reformulation: As he was jogging, his tummy was shaking.

tummy shaking

(3) Direct correction: As he was jogging, his tammy was shaked.

The results show that, after studying reformulated and marked

texts and then revising original texts without access to the

reformulated/corrected texts, students benefitted from both error

correction approaches, but students receiving direct correction

statistically outperformed those receiving reformulation feedback in

terms of accurate revisions. Sachs and Polio (2007) indicate that

reformulation is nevertheless a useful feedback approach because it not

only assists learners with tackling surface-level linguistic errors, but

also draws their attention to higher levels of errors, such as style

and organization.

My Experience

I did not have much experience with this reformulation feedback

until I worked on a conference proposal with a U.S. colleague who is

experienced in academic writing and has many publications in various

reputational education journals. Inspired by previous studies on

reformulation, I was interested in taking a second look at my final

version of the proposal, which had been reformulated by my colleague,

and to compare and contrast the differences between my draft and the

revised text.

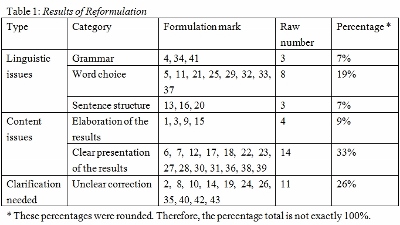

Appendix 1 shows a six-paragraph excerpt from my results

section, selected because this excerpt received the most revisions. The

first section is my draft; the second section is the reformulated text. I

examined the differences in the two columns. During the comparison of

both texts, I identified the corrected parts and tried to understand the

purpose of the correction. Then I tried to induce possible categories

in which to include the feedback. Once a category emerged, I reread the

corrections, confirming or disconfirming the category. Six categories

emerged: grammar, word choice, sentence structure, elaboration of the

results, better description, and unclear correction. These categories

can be generalized into three types: linguistic issues (local level of

writing), content issues (global level of writing), and clarification

needed. The linguistic issues are grammar, word choice, and sentence

structure. The content issues consist of elaboration of the results

(i.e., to further explain the result) and better description (i.e., to

present the results more clearly). The final type, clarification needed,

encompasses revisions for which I did not understand my colleague’s

rationale.

Forty-three changes are identified and displayed in Appendix 2.

A summary of each revision category for these changes is listed in

Table 1, including the number and percentage of corrections in each

category (click on image to enlarge).

I assigned the corrections to the category that best fit,

although some corrections could fit into more than one category. When

more than one possible category for a correction existed, I discussed

the correction with a doctoral student who had taught second language

writing for several years, and came to a final conclusion. After

searching for differences in two texts and placing them into different

categories, I made efforts to understand the corrections. This

experience confirmed Sachs and Polio’s (2007) position that

reformulation helps learners focus on the revised text in terms of

various writing levels, as discussed below.

The percentages of corrections in the six categories are not

equal. At the local level, more corrections were concerned with word

choice. My colleague replaced my general or inaccurate word selection

with precise words. For example, I realized that development was not an appropriate word for

describing discourse moves and that fluctuation was

an accurate word to explain an up-and-down situation. With regard to the

global level, there were more pieces of feedback on new and better

expression. I learned that I could use words in various ways. For

example, in my original text, I wrote: “Monica had a higher percentage

of uniqueness codes than Drinna. Fifty-three percent of Monica’s posts

and 49% of Drinna’s posts were coded as showing unique.” My colleague

reformulated it this way: “Monica also had a slightly higher percentage

of uniqueness codes than Drinna, with 53% of Monica’s

total number of posts and 49% of Drinna’s total number of posts

displaying distinctiveness” (emphasis added). My colleague skillfully

combined the two sentences into one sentence and used with to elicit the two participants’ percentages of

discourse moves. I was excited about reading these reformulated

corrections. Previously, I did not realize that I could use with to express conjunction. This correction

broadened my writing repertoire.

Furthermore, I was fascinated by the reformulated sentences

with regard to better expression. For instance, my original sentence was

“Drinna’s anti-uniqueness codes comprised of 18 percent of her all

posts and 14% of Monica’s posts were anti-uniqueness codes.” In

contrast, my colleague redrafted the sentence as “For Drinna, 18% of her

postings were coded with anti-uniqueness codes whereas for Monica, 14% of her total postings

received such codes” (emphasis added). The colleague

adeptly contrasted the two participants and specifically made the

difference of the participants’ coding results stand out more. After the

colleague’s reformulation of the text, the results section in the

proposal more vividly presented better clarity. Several of my

native-English-speaking classmates read the reformulated text and

recognized that it was well written. More surprisingly, there were no

advanced, sophisticated words used in the revised text, but rather, my

colleague used common words. I learned that the power of straightforward

words can still communicate ideas in a direct and nuanced way as long

as they are well organized. In addition, by close observation of the

reformulated text, I noticed the correct words that I always misused and

understood how to present the finding succinctly and clearly.

In contrast to the five categories of linguistic feature

corrections, I had several questions about some reformulated phrases and

sentences, which I categorized as “unclear correction.” The percentage

of unclear correction was the second highest among all categories. I did

not understand why or whether the corrected sentences were better than

the original ones. I felt uncertain about some changes that my colleague

made, like dividing my sentence into two sentences, deleting certain

words, or using punctuation to present the same idea. For example, my

original text was “Drinna showed moderately high need for uniqueness

(3.29 out of 5) and strongly agreed that it is important to express

distinctive ideas in class whereas Monica displayed

low need for being unique (2.07 out of 5) and strongly disagreed the

importance of having distinctive ideas in class to her” (emphasis

added), but my colleague reformulated it as “Drinna showed moderately

high need for uniqueness (3.29 out of 5) and strongly agreed that it is

important to express distinctive ideas in class. Monica displayed low

need for being unique (2.07 out of 5) and strongly disagreed that

conveying distinctive ideas in class was important to her.” I did not

know the reason that she deleted my whereas.

Also, word replacement aroused my curiosity. My colleague

substituted appeared for seemed in

the original sentence “She . . . seemed to be more

deliberate about how she created her posts” (emphasis added). So far, a

simple and quick (but maybe insufficient) answer to explain the “unclear

correction” revision was different writing styles and instinctive

language sense. I suddenly remembered that my native-English-speaking

writing tutors occasionally said, “Well, I don’t know how to explain it

to you, but it just sounds better and natural to me!” when I raised

tricky questions with them. It is suggested that more meetings with

writing experts is one of the solutions to further clarify my problems.

Another possible way is to read more good writing pieces and keep

mindful of their expressions for further reflection.

Conclusion

There are several advantages and disadvantages of using

reformulation as a way to give feedback on second language learners’

writing. With regard to the positive side, reformulation allows learners

to compare the difference between their own and the reformulated

version and further to push themselves to reflect on why the

reformulated version is better than their own. I was exposed to examples

of better expression of meaning and correct usage of English in

academic writing. Moreover, reformulation involves feedback on both the

local and global levels of writing, giving learners comprehensive

feedback (Sachs & Polio, 2007). For me, the comparison of the

reformulated text and my original text is like a treasure hunt game. I

have to “dig out” my writing errors and examine correct writing

expressions. By reading the reformulated text, it challenges my previous

writing belief and further stimulates me to find answers to this

question: Why does it look better when it is written like

this?

As for the negative side of reformulation, it is an implicit

feedback approach. I have to spend more time searching for the

correction. As Ellis (2009) suggests, reformulation may impose the

burden on learners of identifying writing revisions that have been made.

Language learners have to pay close attention and exert effort to note

the difference. Without such attention and effort, the learners may not

receive the potential benefits of reformulation. Furthermore,

reformulation may be better suited for advanced learners who can analyze

the comparison between their writing and the reformulated text, rather

than for novice learners who may feel overwhelmed and have many

questions about why their writing is reformulated in a particular way.

To overcome the weakness of the reformulation, writing

instructors or more knowledgeable writers could hold writing conferences

to clarify students’ questions about the corrections. Such conferencing

can motivate and encourage learners to look back at the revisions and

identify changes they do not understand, thus enabling them to receive

more benefits from the reformulation approach and further improve their

writing.

References

Ellis, R. (2009). A typology of written corrective feedback

types. ELT Journal, 63(2), 97–107.

Lapkin, S., Swain, M., & Smith, M. (2002).

Reformulation in the learning of French pronominal verbs in a Canadian

French immersion context. Modern Language Journal, 86, 486–506.

Sachs, R., & Polio, C. (2007). Learners’ uses of two

types of written feedback on a L2 writing revision task. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 29(1),

67–100.

Schmidt, R. (1990). The role of consciousness in second

language learning. Applied Linguistics, 11(2),

129–158.

Schmidt, R., & Frota, S. (1986). Developing basic

conversational ability in a second language: A case study of an adult

learner of Portuguese. In R. R. Day (Ed.), Talking to learn:

Conversation in second language acquisition (pp. 237–326).

Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Thornbury, S. (1997). Reformulation and reconstruction: Tasks

that promote “noticing.” ELT Journal, 51,

326–335.

Li-Tang Yu is a doctoral student in the Foreign

Language Education Program at the University of Texas at Austin. His

research interests include new literacies, computer-assisted language

learning, second language acquisition, and L2 literacy development. He

taught EFL at the elementary school and university levels in Taiwan.

appendix1a

appendix1b

appendix2a

appendix2b |